Note: This blog article was edited on 17/04/19 to include recent developments.

This year, Australian voters will elect members of the 46th Parliament. According to s. 28 of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, an election for the members of the House of Representatives must be held every three years. The term of service of a senator is six years, commencing on the first day of July following the day of their election, although half-Senate elections are required to be held every three years, thereby rotating half the senators each election. Incidentally, elections must always be held on a Saturday.

The Constitution does not actually require elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate to be held simultaneously. While there is a precedent for holding separate elections, this is rare, and both governments and voters have long preferred that elections for the two Houses be held simultaneously to limit costs. In any event, voters could have ‘campaign fatigue’ if two federal elections were held in the same year.

A half-Senate election for the State senators only must be held no later than 18 May 2019, and 2 November 2019 is the latest date that an election must be held for the members of the House of Representatives and the Territory senators. It is improbable that separate elections will be held, so while the Government has not yet announced the date of the election, it is expected that a simultaneous election will be held on either Saturday 11 or 18 May 2019. This has forced the rescheduling of the Federal Budget (which has been brought down on the second Tuesday in May since 1994) to Tuesday 2 April 2019.

While the two major parties are yet to officially launch their election campaigns, details of the Opposition’s tax and superannuation policies are starting to emerge.

![]() Update since original release of blog

Update since original release of blog

The Prime Minister has called a Federal election for Saturday 18 May 2019.

Note that the realisation of Labor’s policies outlined below are dependent on:

On 21 June 2018, the Government secured its personal tax cuts package worth $13.4 billion over the forward estimates period to be delivered in three stages from 1 July 2018, 1 July 2022 and 1 July 2024.

Labor has stated it will support the first stage of the Government’s personal tax cuts package that began on 1 July 2018, but as part of its promise to deliver larger, permanent, tax cuts from 1 July 2019, it intends to unwind Stages 2 and 3 (legislated from 2022 and 2024).

![]() Update since original release of blog

Update since original release of blog

In a media release issued on 4 April 2019 accompanying his Budget-in-Reply speech, the Opposition Leader, Bill Shorten, announced that, under Labor, workers earning up to $37,000 a year will receive a tax cut from 1 July 2018 of up to $350 by way of an increase in the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO).

This further increases the LMITO beyond the Government’s plan (announced as part of the 2019–20 Federal Budget) to increase the offset from $200 to $255 from 1 July 2018. Under Labor, those earning between $37,000 and $90,000 would receive the maximum offset of $1,080, whereas under a Coalition government only those earning between $48,000 and $90,000 would receive the full $1,080.

Labor has stated that it remains opposed to the removal of the Temporary Budget Repair (TBR) levy which was imposed at the rate of two per cent of each dollar of a taxpayer’s taxable income over $180,000 from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2017 (i.e. the 2014–15 to 2016–17 income years only).

Labor’s position is that providing a ‘tax cut to people earning more than $180,000 isn’t justified’. Labor describes the reduction in the rate of tax when the TBR levy was removed in 2017 as a ‘tax cut’.

Accordingly, Labor intends to increase the top personal tax rate for four years from 45 per cent to 47 per cent (to 49 per cent including the Medicare levy) for those individuals whose taxable income exceeds $180,000. It is unclear whether this would be achieved by reinstating the now-lapsed two per cent TBR levy or increasing the highest marginal tax rate from 45 to 47 per cent, and the start and end dates of the proposed tax increase have not been announced.

![]() Update since original release of blog

Update since original release of blog

In a radio interview on 5AA Mornings on 5 April 2019, the Shadow Assistant Treasurer, Andrew Leigh, confirmed that Labor would reintroduce the TBR levy from 1 July 2019.

This would also have the effect of returning the FBT rate to 49 per cent (as it was for three years) and would result in consequential changes to other tax rates linked to the top personal tax rate.

During 2018, Labor supported the Government’s 2017–18 Federal Budget measure which proposed to increase the Medicare levy by 0.5 per cent (lifting it to 2.5 per cent) from 1 July 2019 but was opposed to the increase for those earning less than $87,000.

When the Government announced in the 2018–19 Federal Budget that it would not proceed with the proposed increase — because the planned expenditure on the National Disability Insurance Scheme could now be funded through the Budget — Labor reversed its position and no longer supports an increase in the Medicare levy for those earning above $87,000.

Proposed consequential changes to other tax rates linked to the top personal tax rate, such as the FBT rate, will also not proceed.

Australia is only one of three countries in the world (along with New Zealand and Malta) with a full imputation system, and is the only country that offers fully refundable franking credits.

In what is arguably one of the most divisive and controversial Labor policies, it is proposed that, from 1 July 2019, Labor would reverse the decision of the Howard Government to allow cash refunds from 1 July 2000 for excess franking credits. Under this policy, franking credits for individuals and superannuation funds would no longer be a refundable tax offset and would return to being a non-refundable tax offset — cash refunds would not be available if the franking credits exceed the taxpayer’s tax liability.

Labor expects that the policy won’t affect 92 per cent of individual taxpayers (based on data from 2014–15 tax returns).

Self managed superannuation funds (SMSFs) account for 90 per cent of all cash refunds paid to superannuation funds — even though, according to Labor, SMSFs account for less than 10 per cent of all superannuation members in Australia — so it not expected that APRA-regulated superannuation funds will be significantly affected.

More detail is contained in Labor’s fact sheet, including the history of the current regime and Labor’s justification for saving the Budget $11.4 billion over the forward estimates period and $59 billion over the decade to 2028–29.

![]() Comment

Comment

Labor has been silent on whether its franking credit policy would affect companies that are not eligible to receive refundable tax offsets resulting from excess franking credits but can convert excess franking credits into carry forward tax losses under s. 36-55 of the ITAA 1997.

Exclusions would apply to:

Under the Pensioner Guarantee:

![]() Note

Note

Labor’s use of the term ‘pensioner’ here refers to individuals receiving a government pension, not those drawing an income stream (commonly referred to as a ‘pension’) from their superannuation fund.

On 19 September 2018, the Treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, asked the Standing Committee on Economics to inquire into the implications of removing refundable franking credits. Under the Terms of Reference, the Committee will inquire into and report on the use of refundable franking credits, their benefits and the implications of their removal, including:

Submissions made to the inquiry and details of public meetings are available here.

In 1985, the Labor Hawke Government (Paul Keating was the Treasurer at the time) changed the negative gearing rules to remove the quarantining of property losses and allowed them to be applied against income from labour (i.e. wages). Then, six months later, after the tax summit in July 1985, the Hawke Government reversed this change, once again quarantining negatively geared interest expenses on new transactions so that they were claimable only against rental income, not other income (these losses were able to be carried forward to offset property income in later years).

The inability to apply negatively geared property losses against other income was deeply unpopular with property investors, so in July 1987, after successful lobbying by the property industry citing concerns about rising rents and lack of affordable housing, the Hawke Government once again reversed its decision and allowed negatively geared property losses to be applied against income from labour; this treatment has remained untouched to this day — negative gearing has continued to be a divisive tax policy topic.

In another highly controversial policy, Labor proposes to limit negative gearing to new housing from a yet-to-be-determined date after the next election. All investments made before this date will not be affected by this change and will be fully grandfathered.

This will mean that taxpayers will continue to be able to deduct net rental losses against their other taxable income, providing the losses come from newly constructed housing.

Notably, the proposed changes to negative gearing would apply not only to property but also to share and similar investments, so that losses from new investments in shares and existing properties would be quarantined against investment income, and could continue to be carried forward to offset the final capital gain resulting from the sale of the investment.

![]() Update since original release of blog

Update since original release of blog

In an address on 29 March 2019 to the Financial Services Council, the Shadow Treasurer, Chris Bowen, announced that Labor’s reforms to negative gearing will commence from 1 January 2020 and confirmed that there will be grandfathering of existing investments acquired before that date.

Labor proposes to halve the CGT discount for all assets purchased after a yet-to-be-determined date after the next election. This will reduce the CGT discount for assets that are held for more than 12 months from the current rate of 50 per cent to 25 per cent. The change would not affect investments held by superannuation funds which instead attract a one-third CGT discount (i.e. a tax rate of 10 per cent on capital gains) when the asset is held for more than 12 months.

Grand-fathering will apply to all investments made before the date of effect, which will continue to attract the full 50 per cent discount.

![]() Comment

Comment

Labor’s policy document states that:

The CGT discount will not change for small business assets. This will ensure that no small businesses are worse off under these changes.

It is unclear whether this is referring to the small business 50 per cent reduction which is available as part of the small business CGT concessions in Div 152 of the ITAA 1997.

On 11 May 2017, as part of the Budget-In-Reply speech delivered by the Leader of the Opposition, Bill Shorten, reference was made to 48 Australian taxpayers who, in 2014–15, earned more than $1 million and paid no tax at all, not even the Medicare levy. Using deductions, they reduced their taxable income from an average of nearly $2.5 million to below the tax-free threshold. One of the biggest deductions claimed was amounts paid to their accountants — averaging over $1 million.

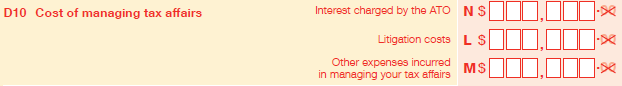

This prompted Labor to announce that it would cap the amount individuals can deduct for the management of their tax affairs at $3,000. According to Labor, the change from a yet-to-be-determined date would affect fewer than one per cent of taxpayers and would save the Budget $1.3 billion over the medium-term.

No further detail on this policy is available so it is difficult to determine how the policy would apply in practice, but the following issues have been identified by the tax profession:

These types of arrangements generally involve additional work by tax agents. The more complex the tax affairs, the higher the cost of managing those affairs, and $3,000 may be well below the fee actually being charged to the taxpayer.

Notably, the tax return for 2014–15 (see below) didn’t segregate the types of claims that could be made at item D10,

![]()

however, for the first time, the tax return for 2017–18 (see below) now separately identifies the types of claims that can be made at item D10, providing greater transparency to the ATO.

On 30 July 2017, Labor announced that it would tackle a perceived loophole that allows the use of discretionary trusts to minimise tax paid by allocating income to family members who have lower marginal tax rates by accessing multiple tax-free thresholds, unlike wage-earners who can only access one tax-free threshold.

Statistics from the Parliamentary Budget Office from 2013–14 show that the greatest proportion of taxpayers who receive a discretionary trust distribution are those who earn less than the tax-free threshold of $18,200.

Labor will effectively extend the principle of John Howard’s original reform which introduced Div 6AA into the ITAA 1936 from 1 July 1979 to target trust distributions made to minors. Under the proposed reforms, Labor will introduce a new standard minimum tax rate of 30 per cent on discretionary trust distributions made to adult beneficiaries from 1 July 2019.

In circumstances where the minimum tax rate on discretionary trust distributions is lower than what would be paid under the normal marginal tax scales, the higher rate would apply.

Labor states that:

A 30 per cent minimum tax rate is less punitive than John Howard’s reform of penalising income distributions to minors at the top marginal tax rate.

Labor estimates that the reforms will not affect 98 per cent of all individual taxpayers in Australia and will affect 318,000 discretionary trusts.

![]() Comment

Comment

It is unclear what mechanism would be used to impose the minimum 30 per cent tax rate; it could be a withholding tax imposed at the trustee level or additional top-up tax payable by the adult beneficiary.

The minimum 30 per cent tax rate would apply only to discretionary trusts, and would not apply to non-discretionary trusts such as:

Labor’s policy will also not apply to:

This saga-laden topic has been the subject of a number of Banter Blogs, including:

On 26 June 2018, Bill Shorten announced that Labor would repeal the enacted tax cuts for companies with an annual aggregated turnover of between $10 million and $50 million. At that time, Labor was still deciding whether it would also repeal the enacted tax cuts for smaller companies with an annual turnover of between $2 million and $10 million. It was committed to retaining the lower tax rate for companies under $2 million turnover.

However, on 29 June 2018, following a shadow cabinet meeting, Bill Shorten reversed his position and announced that Labor would not repeal the enacted tax cuts that are already legislated to come into effect. He stated:

I now accept that simply stopping at $10 million would have created more confusion, uncertainty.

Accordingly, this means that companies under $50 million turnover will retain their tax cuts and Labor will not go to the election undertaking to increase company tax rates that have already fallen or are legislated to fall.

Notably, Labor supported without delay an amending bill in October 2018 which fast-tracked the previously legislated reduction of the tax rate for companies that are base rate entities.

Currently, businesses can claim a deduction for the decline in value of their depreciating assets over their effective lives, unless the taxpayer is a small business entity in which case an immediate deduction is available as long as the asset cost less than $20,000. This concession is legislated to expire on 30 June 2019, when the instant asset write-off threshold reverts to $1,000.

On 29 January 2019, the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, announced that the Government would extend the instant asset write-off threshold — for the third time — to 30 June 2020, and increase the threshold from $20,000 to $25,000 with effect from 29 January 2019. This is subject to the passage of amending legislation which is expected to be introduced into Parliament in February 2019.

Labor has announced it will back the extension so these two changes should move through Parliament without delay during February 2019.

Labor has released a fact sheet on its proposed Australian Investment Guarantee (AIG) which will allow all businesses from 1 July 2020 to:

| Example adapted from Labor fact sheet |

Manufacturing company A is struggling to purchase a new $10 million piece of machinery that would greatly enhance its productivity and output allowing it to expand and create additional jobs.

Current arrangements (without the Australian Investment Guarantee)Under normal depreciation rules for this piece of machinery (assuming a straight line depreciation method) manufacturing company A is allowed to deduct 10 per cent or $1 million of the $10 million in each year over the effective 10-year life of the asset. Arrangements with Labor’s Australian Investment GuaranteeUnder Labor’s AIG, manufacturing company A will be able to immediately expense 20 per cent ($2 million) of its investment in the first year. The remaining 80 per cent ($8 million) would then be depreciated over the effective life of the asset from the first year in line with the original depreciation schedule — which in this case is 10 per cent per year, or $800,000 of the $8 million. This means Manufacturing company A can write off a total of $2.8 million in the first year ($2 million plus $800,000) of its investment (instead of $1 million under existing arrangements). This means the company has additional immediate cash flow, which tips the balance and triggers the positive investment decision. The company can then use the extra cash flow to bring forward other investments and hire new employees. |

The AIG is a permanent accelerated depreciation scheme and would operate indefinitely.

![]() Note

Note

Labor has delayed the introduction of the AIG by 12 months to 1 July 2021 due to its supporting the Government’s decision to fast-track the reduction of the corporate tax rates for companies under $50 million.

The following assets will be eligible for the AIG:

![]() Comment

Comment

It is unclear whether Labor would retain some type of permanent asset write-off for assets costing less than $20,000 (which is being increased to $25,000 from 29 January 2019) and whether such a write-off would be confined to small business entities or available to all businesses.

The following assets will not be eligible for the AIG:

In the ALP National Platform Consultation Draft released in April 2018, Labor set out its proposed superannuation policies.

Labor will reduce the non-concessional contributions cap from $100,000 to $75,000. No start date has been announced.

Where an individual’s Div 293 income (taxable income plus superannuation contributions) exceeds the Div 293 income threshold, an additional 15 per cent tax is payable on concessional contributions (i.e. a total tax rate of 30 per cent instead of 15 per cent).

The Div 293 income threshold was $300,000 from 2012–13 to 2016–17 and was reduced to $250,000 from 1 July 2017.

Labor will reduce the Div 293 income threshold from $250,000 to $200,000. No start date has been announced.

The catch-up concessional contributions measure allows individuals to access their unused concessional contributions caps on a rolling basis for five years, provided their total superannuation balance is less than $500,000 at the end of the previous financial year. Amounts carried forward that have not been used after five years will expire. The measure started on 1 July 2018 but 2019–20 is the first financial year in which individuals can access unused concessional contributions.

Labor will remove the catch-up concessional contributions measure. No start date has been announced.

Labor will remove the tax deductibility of personal contributions, which has been available since 1 July 2017. No start date has been announced.

This infers that the unpopular ‘10 per cent rule’ could be reinstated which would significantly restrict the ability of individuals to claim a deduction for personal contributions, forcing them to utilise salary sacrifice arrangements through employers where available or forgo the deduction.

Labor will end the freeze on the increase in the rate of the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent (when prudent).

The rate of SG is legislated to increase to:

Labor has announced it will phase out the $450 minimum monthly income threshold for eligibility for SG contributions, in recognition that the income eligibility threshold disadvantages people who work part-time, casually and in multiple low‑paid jobs.

No start date has been announced.

Labor has announced it will prospectively restore the prohibition on direct borrowing by SMSFs for housing investments, i.e. remove the ability for SMSFs to utilise limited recourse borrowing arrangements to acquire property. This infers that existing arrangements would be grand-fathered.

No start date has been announced.

Labor has announced it will implement a number of measures targeting ‘multinational tax avoidance and high wealth tax dodgers’, saving the Budget $4.8 billion over the next decade.

These measures include:

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.