NOTE: In this article, all section references are to the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997.

On 9 May 2017, as part of the 2017–18 Federal Budget, the Government announced that it would make changes to the CGT main residence exemption (MRE). On 23 October 2019, the Treasury Laws Amendment (Reducing Pressure on Housing Affordability Measures) Bill 2019 (‘the Bill’) was introduced into Parliament. On 5 December 2019, the Bill was passed by the Senate without amendment, and was enacted on 12 December 2019 as Act No. 129 of 2019 (’the Act’).

Schedule 1 to the Act contains measures to deny the MRE to taxpayers who — at the time of the CGT event (i.e. when they enter into a contract to sell a dwelling that has been their main residence) — are a non-resident for tax purposes (hereafter referred to as simply ‘non-resident’).

Amendments to give effect to these measures were previously proposed in the Treasury Laws Amendment (Reducing Pressure on Housing Affordability No. 2) Bill 2018 (‘the original Bill’) which was introduced into Parliament on 8 February 2018 and was before the Senate when Parliament was prorogued prior to the 2019 Federal election. Accordingly, the original Bill lapsed on 1 July 2019 with the commencement of the 46th Parliament.

The measures were announced in the 2017–18 Federal Budget in the following brief terms:

The Government will extend Australia’s foreign resident capital gains tax (CGT) regime by: … denying foreign and temporary tax residents access to the CGT main residence exemption from 7:30 PM (AEST) on 9 May 2017, however existing properties held prior to this date will be grandfathered until 30 June 2019; …

The Government announced on 18 December 2017, as part of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2017–18, that following consultation the Government amended the proposal so that ‘temporary tax residents’ who are Australian residents will be unaffected. This ensures that only Australian tax residents, including temporary residents, can access the MRE. Accordingly, only foreign residents (i.e. non-residents) are affected by this measure.

These measures apply to CGT events happening on or after 7.30 pm (AEST) on 9 May 2017.

A transitional rule will not deny the MRE to taxpayers who held the dwelling immediately before 7.30 pm (AEST) on 9 May 2017 if:

This allows affected taxpayers until 30 June 2020 to sell their former homes without being subject to the new measures (the original Bill proposed a transitional period ending on 30 June 2019). The listing and sale of a property can take, on average, around 80 days, so affected taxpayers considering selling their properties ahead of 30 June 2020 to avoid being subject to the new measures will ideally need to list their properties by March 2020.

While these measures appear to commence on 9 May 2017, the practical effect is that it could result in the retrospective denial of the MRE as far back as 20 September 1985: the commencement of the CGT regime and the MRE. Under these amendments, the availability of the MRE to a taxpayer is based on their tax residency status at the time of the CGT event, irrespective of the use of the dwelling or the taxpayer’s residency status throughout the ownership period.

Senate Economics Legislation Committee

The Senate Economics Legislation Committee, which reported on the original Bill on 23 March 2018, made the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1

The committee recommends that the Australian Government ensures that Australians living and working overseas are aware of the changes to the CGT main residence exemption for foreign residents, and the transitional arrangements, so they are able to plan accordingly.

Recommendation 2

The committee recommends that the [bill] be passed.

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, which reported on the Bill on 13 November 2019 (Scrutiny Digest Number 8), made the following remarks:

1.90 The committee has a long-standing concern about provisions that apply retrospectively, including provisions that back-date commencement to the date of the announcement of particular measures (i.e. ‘legislation by press release’), as such an approach challenges a basic value of the rule of law that, in general, laws should only operate prospectively. The committee has particular concerns where legislation will, or might, have a detrimental effect on individuals.

…

1.92 The committee notes that, in this case, the bill that first contained this measure—the Treasury Laws Amendment (Reducing Pressure on Housing Affordability Measures No. 2) Bill 2018—was introduced almost nine months after the budget announcement on 9 May 2017, and this bill was introduced well over two years after the announcement.

…

1.94 With respect to the amendments in Schedule 1, the explanatory memorandum states that the measures need to generally apply from the date of announcement to prevent opportunities for affected taxpayers or entities to dispose of their dwelling or assets to avoid application of the measures.

…

1.97 The committee reiterates its long-standing concerns that provisions with retrospective application (including where provisions are back-dated to the date of announcement of an initiative) challenge a basic value of the rule of law that, in general, laws should only operate prospectively.

1.98 In light of the explanation provided in the explanatory memorandum as to the retrospective application of the amendments proposed by the bill, the committee draws its scrutiny concerns to the attention of senators and leaves to the Senate as a whole the appropriateness of applying the amendments in the bill on a retrospective basis.

![]() Comment

Comment

The Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills was concerned about the retrospectivity arising from back-dating the provisions to the date of announcement — the Bill was ultimately passed by the Senate 940 days after the date on which the measures were first announced.

However, the Committee, and the Senate more broadly, has overlooked the more fundamental retrospective nature of these amendments; that is, that the capital gain is required to be calculated using the original cost base, thereby taxing what were previously exempt capital gains from up to 3½ decades ago (i.e. since 20 September 1985).

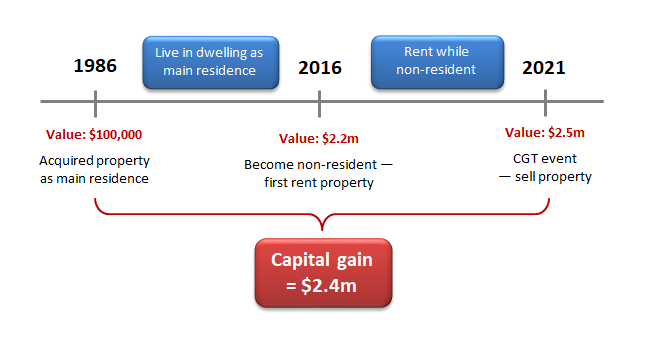

An Australian taxpayer, Ozzie, has always been an Australian tax resident. He bought a dwelling in Australia on 1 July 1986 for $100,000 and used it as his home; to date, it has never been rented out, and the dwelling has always been his main residence.

On 30 June 2016, after deciding to accept a job overseas, Ozzie relocated offshore for an indefinite period and became a non-resident. At the time he relocated, Ozzie’s home was worth $2.2 million.

Ozzie decides to stay overseas. Five years later, on 30 June 2021, he sells the dwelling that, prior to moving overseas, had been his home for 30 years. Because Ozzie is a non-resident at the time of the CGT event, he is not entitled to the MRE — at all. Accordingly, he will have a taxable capital gain of $2.4 million.

This may be depicted as follows:

Ozzie cannot:

This is because all these concessions are contained in the MRE rules in Subdiv 118-B that rely on the taxpayer being entitled to claim a partial MRE — and Ozzie is not entitled to any MRE.

CGT event I1 (s. 104-160) happens when an individual stops being an Australian resident, causing a deemed disposal of their CGT assets at their market value and allows the taxpayer to choose to defer the tax on these assets.

However, CGT event I1 does not happen when Ozzie stops being an Australian resident, because CGT event I1 applies only to CGT assets that are not taxable Australian property — in this case, Ozzie’s dwelling continues to be taxable Australian property and therefore remains within the Australian CGT regime.

Ozzie will have a taxable capital gain of $2.4 million, without access to any MRE. Is he entitled to any CGT discount as a non-resident? Non-residents have not been entitled to the CGT discount since 8 May 2012.

Under s. 115-115:

The Act contains new measures which allow a non-resident to continue to access the MRE for CGT events concerning certain ‘life events’ if they have been a non-resident for a continuous period of no more than six years at the time of the CGT event. This is referred to in the legislation using a double negative — i.e. a person who is not an ‘excluded foreign resident’.

An ‘excluded foreign resident’ is someone who has been a foreign resident for a continuous period of more than six years. Importantly, an ‘excluded foreign resident’ is not able to access the MRE even if certain life events occur to them.

The new measures do not apply if:

A person satisfies the ‘life events test’, at the time the CGT event happens, if:

Terminal medical condition

A ‘terminal medical condition’ is defined in regulation 303-10.01 of the Income Tax Assessment Regulations 1997 and requires that two medical practitioners certify that death is likely to result from the illness or injury within 24 months of the certification.

There is an additional requirement in the case of a child under 18 years of age that the child was suffering from a terminal medical condition during at least part of the period of foreign residency (i.e. they cannot have suffered from that condition only while the taxpayer was a resident).

Marriage or relationship breakdown

This life event requires that the CGT event occurs because of a matter referred to in s. 126-5(1) (about marriage or relationship breakdown) involving the taxpayer or their spouse. Importantly, even if one of the matters in s. 126-5(1) has occurred during the period of foreign residency, the MRE will not be available if the CGT event does not occur because of one of those matters.

Unresolved issue

Under s. 118-178, where a property is transferred from the taxpayer’s former spouse or partner (hereafter referred to as simply ‘former spouse’), and there was a CGT roll-over under Subdiv 126-A (about marriage or relationship breakdown):

Example — treatment under the current law

Mark and Kellie were married for 15 years. Following their divorce, Mark transferred the ownership interest he held in a property to Kellie. She is taken to have acquired the property when Mark acquired it, and pursuant to the CGT roll-over in Subdiv 126-A and s. 118-178, she is taken to have:

Accordingly, if the property was only ever used as Mark’s main residence, Kellie will be taken to have acquired it when Mark acquired it for what he paid for it, and (assuming she lives in the property as her main residence until she sells it), she will be entitled to a full MRE. If Mark had rented the property before he transferred it to Kellie, she would have a partial MRE.

Issue

Say, following the divorce and transfer of the property from Mark to Kellie, Mark becomes a non-resident. What is the impact on Kellie when she subsequently sells the property after continuing to treat the property as her main residence throughout her ownership period?

Treatment under the new law

The Act is silent on its interaction with s. 118-178 which deals with the application of the MRE following a previous roll-over under Subdiv 126-A.

There are two possible interpretations:

1. Mark’s foreign residency status has no impact on Kellie’s tax position

As the CGT event (i.e. the sale of the property) happens to Kellie, and not to Mark, his residency status is irrelevant to her eligibility for the MRE. This means that Mark’s main residence days continue to be taken to be her main residence days, and (on the above facts) she would be entitled to a full MRE on sale.

2. Mark’s foreign residency status impacts on Kellie’s tax position

Although the CGT event happens to Kellie, and not to Mark, he is a non-resident at the time of the CGT event. Accordingly, Mark’s main residence days are ‘zeroed out’ and Kellie is unable to recognise his main residence days. This would result in Kellie being entitled to only a partial MRE on sale.

If this second interpretation is correct, residents could be taxed on the sale of their homes transferred to them following a marriage or relationship breakdown by their former spouse, due to the foreign residency status of their former spouse.

This raises the following dilemmas:

To correctly calculate the capital gain, Ozzie will need to determine the cost base of the property. This will be a major issue for many affected taxpayers who may never have kept records of these costs because they didn’t think it was necessary; after all, everyone knows that the sale of a dwelling that is your main residence is exempt from CGT.

Ozzie could not have foreseen all those years ago that the Government would retrospectively deny him the MRE, causing the sale of his home to be taxable in the future due to his foreign residency status.

Ozzie will need to determine the following cost base elements:

| Element of cost base | Explanation |

| 1st element | Purchase price of the property |

| 2nd element | Acquisition (and selling) costs such as stamp duty and conveyancing services (details of selling costs are more likely to be available because they are incurred at the time of the sale) |

| 3rd element | Holding/ownership costs, such as interest, rates, insurance, and repairs and maintenance, but only where the property was acquired after 20 August 1991 |

| 4th element | Improvements, such as renovations or other improvements |

| 5th element | Rarely applicable in these cases as it relates to capital expenditure incurred to establish, preserve or defend title to the asset. |

If Ozzie is unable to substantiate each element of the cost base of the property, he cannot simply use an estimate of these amounts. Accordingly, there is a risk that his taxable capital gain will be larger than should otherwise be the case due to a lack of substantiation. Contrast this with a taxpayer who acquires a dwelling after these changes are enacted with the knowledge that, under the new rules, there is a possibility that they will not be entitled to the MRE — they would be in a better position to prospectively retain all relevant cost base records from the date of acquisition to maximise their cost base and minimise their eventual taxable capital gain.

If Ozzie moves back to Australia after 30 June 2020 and re-establishes himself as a resident, then sells the dwelling, he would not be a non-resident at the time of the CGT event and he would be entitled to the MRE. Accordingly, he could access a partial MRE, the absence rule in s. 118-145 and the cost base-market value deeming rule in s. 118-192 as applicable.

Paragraph 1.24 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Act explains that the general anti-avoidance rules in Part IVA may be applied to arrangements that have ‘been entered into by a person for the sole or dominant purpose of enabling that person or another person to obtain the [MRE]’. There is no prescribed period that a person would need to return to Australia for to re-establish their residency; this is question of fact.

If Ozzie dies while he is overseas, his interest in the dwelling will pass to the beneficiaries (hereafter simply referred to as ‘the beneficiary’) of his deceased estate in accordance with the wishes set out in his Will (or according to the laws of intestacy of the relevant jurisdiction if he dies without a valid Will).

Ozzie is not an excluded foreign resident at the time of his death

Assume that Ozzie dies as a non-resident on 3 June 2020.

The main residence days of a non-resident who dies may be recognised by a beneficiary of the person’s estate or a person surviving the non-resident provided the person had not been a non-resident for a continuous period of more than six years. This effectively means that a person’s foreign residency status at the time of their death will have no impact under the new measures on a deceased estate or a beneficiary of that estate where the person dies in the first six years of being a non-resident.

As Ozzie is not an excluded foreign resident — because he had not been a foreign resident for more than six years at the time of his death — the MRE accrued by Ozzie for the property continues to be available to the beneficiary of his estate.

However, the beneficiary is denied any additional component of the MRE that they accrued in their own right if they are a non-resident at the time a CGT event occurred to the property.

Ozzie is an excluded foreign resident at the time of his death

Assume that Ozzie dies as a non-resident instead on 3 June 2023.

Ozzie is an excluded foreign resident — because he has been a foreign resident for more than six years at the time of his death — so any portion of the MRE accrued by Ozzie for the property is not available to the beneficiary of his estate.

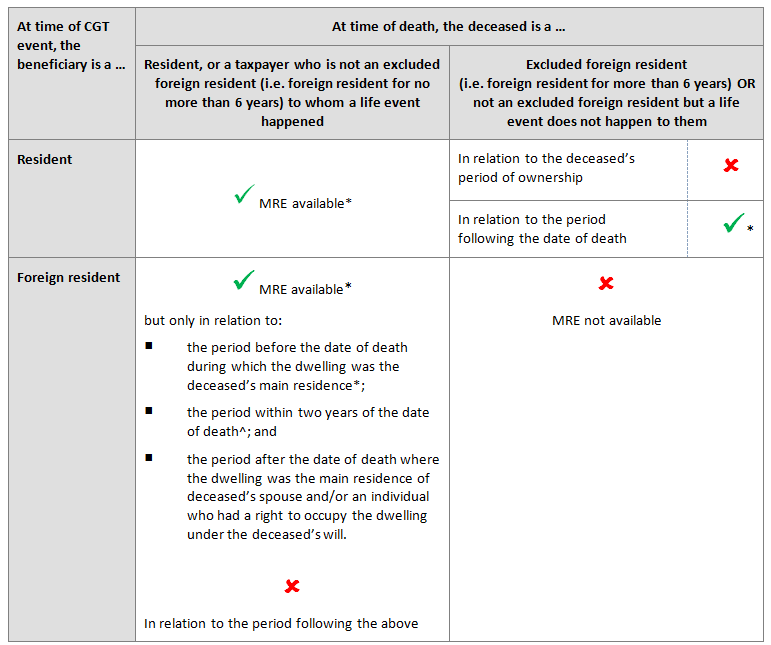

This means that despite Ozzie residing in the property for 30 years as a resident, because he was a non-resident when he died his beneficiary may not be able to claim any MRE — it will depend on their residency status at the time of the CGT event:

This means that if the deceased was a non-resident at the time of death, and the beneficiary is a non-resident at the time of the CGT event, no MRE is available to the beneficiary.

Ozzie is a resident at the time of his death

Had Ozzie been a resident at the time of death (i.e. he re-established his residency before he died and was not an excluded foreign resident at the time of death), the MRE accrued by Ozzie will continue to be available to his beneficiary to the extent of:

However, the beneficiary — to whom the ownership interest in the dwelling passed under the will (but falling short of having a right to occupy the dwelling under the will) — is denied any component of the MRE that is attributable to the period following death when they lived in the dwelling as their main residence if they are an excluded foreign resident at the time of the CGT event.

So to summarise, if Ozzie’s beneficiary is:

Is the MRE available to a beneficiary of a deceased estate who inherits the dwelling?

^ Or within such longer period allowed by the Commissioner.

* Subject to normal MRE rules.

Assume that in February 2020 Ozzie is diagnosed with a terminal medical condition. He decides to return to Australia for medical treatment and to be close to his family and friends. Ozzie returns to Australia but is immediately confined to a hospital bed, where he spends the next four months until his death in June 2020.

While in hospital, Ozzie — as part of attending to his estate planning and financial affairs — may arrange to sell the property before his death. Alternatively, he may still own the dwelling at the time of his death.

If Ozzie is a resident at the time of the CGT event or his death, he is entitled to the MRE, including the absence rule under s. 118-145. But if he is a non-resident at the time of the CGT event or his death, he is not entitled to any MRE.

Ozzie dies without ever moving back into his home. Is Ozzie a resident or non-resident at the time of the CGT event or the time of his death? This is a question of fact, but it may be problematic to establish that Ozzie has re-established his residency simply by virtue of his presence in Australia while he seeks medical treatment. A relevant question would be whether he intended to return to live overseas following his treatment.

![]() Note

Note

In the case of Subrahmanyam and FCT [2002] AATA 1298, the Tribunal concluded that a taxpayer who was in Australia for medical treatment was a resident under the 183-day test on the basis that her ‘usual place of abode’ is not outside Australia. The taxpayer, who had been a medical practitioner in Singapore, moved to Australia almost four years before her death for medical treatment. She maintained her contacts in Singapore and visited many times. She sold her home in Singapore and the proceeds of sale were invested in an Australian interest-bearing account.

Over 2½ years, the author of this article raised the retrospectivity issue repeatedly with Treasury, the Government, the Opposition, the cross-benchers in the Senate, as well as in social media and mainstream media.

The author suggested to Treasury that the policy could be altered to make it more equitable for Australian expatriates, so that the MRE could still generally be denied to non-residents, but that if the non-resident had previously been an Australian resident taxpayer, either one of the following concessions could be allowed:

However, the legislation as enacted contains neither of these two concessions.

Now that these measures are law, it is important to understand the options available to affected taxpayers.

They:

These measures are draconian, retrospective and unfair to Australian expatriates, and thousands of taxpayers will be unfairly taxed on capital gains that accrued when they were residents and lived in their homes.

Removing the MRE retrospectively is equivalent to:

Under the Rule of Law, the law should be capable of being known to everyone, so that everyone can comply. A law that applies retrospectively is not capable of being known, understood, or complied with at the time taxpayers enter into arrangements. Retrospective changes that adversely affect taxpayers should never be passed by our Parliament.

It is grossly unfair that all these years affected taxpayers have operated under laws which exempted their home from CGT and now, due to their status as a non-resident, that exemption is denied.

The only sensible outcome was to apportion the capital gain to exempt any period of residency; however, our calls have fallen on deaf ears. Attention must now turn education, information and the onerous requirements of record-keeping to correctly establish the cost base.

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.