What is the relevance of accounting to tax? Or maybe a better way to frame this question is to consider whether what we do in the accounts, or as part of the entity’s broader compliance activities, will impact the tax outcome. One area where a connection is clear is with respect to trust distributions. How a distribution resolution is worded directly impacts the tax liability. It is important not because it determines what is taxable but because it is the basis for determining where the tax liability falls.

The tax law requires a presently entitled beneficiary to include in their assessable income (under s. 97(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936) a share of the net (i.e. taxable) income of the trust. To establish this share of net income it is necessary to:

This is referred to as the proportionate approach.

The ATO identified in TD 2012/22 ‘the effect of the application of the proportionate approach in any particular case will depend on the facts and circumstances of that case, including the terms of the trust and, where relevant, any resolutions made by the trustee to appoint the income of the trust’.

The way a trustee resolves to distribute income (or perhaps more practically, that way the resolution is drafted), along with the definition of that income in the trust deed, will directly impact the amount of net income the beneficiary pays tax on.

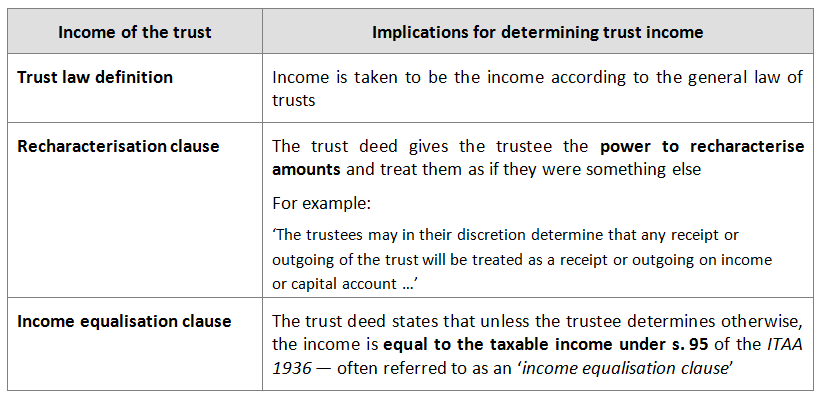

Depending on the specific terms of a trust deed and the extent of the discretion given to the trustee to determine otherwise, there may be three possibilities for determining the income of the trust.

Despite the definition in the trust deed, the Commissioner is of the preliminary view that the statutory context in which the expression ‘income of the trust estate’ is used means that there are limits to the concept of ‘income’ of the trust estate. These limits are set out in draft ruling TR 2012/D1, where the Commissioner takes the preliminary view that where an income equalisation clause is used and an amount is included in the net income of the trust, but is not represented by a net accretion to the trust fund, this amount will not generally form part of the distributable income of the trust.

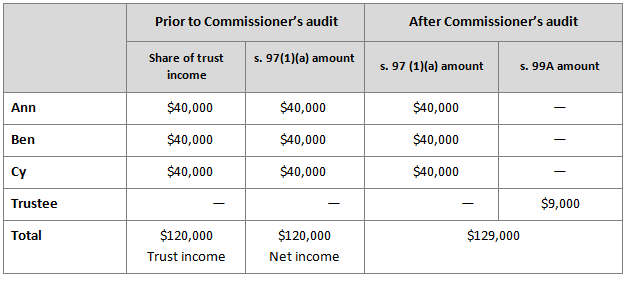

To illustrate how these definitions of income interact with the determination of where the tax liability falls, TD 2012/22 contains examples highlighting how differences in the wording of the trustee resolution alter the determination of the tax liability under the proportionate approach.

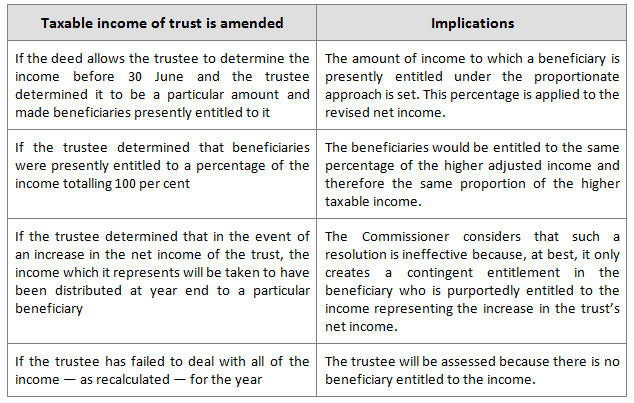

The examples set out below (adapted from the examples in TD 2012/22) illustrate not only how taxable income will be allocated in the first instance, but also the implications where there is an amendment to the net income of the trust. The importance of considering the terms of the trust deed and whether an increase to the net income of a trust also affects the beneficiaries’ proportionate shares of the distributable income should not be underestimated. Does the wording of the trustee’s resolution really do what it purports to do?

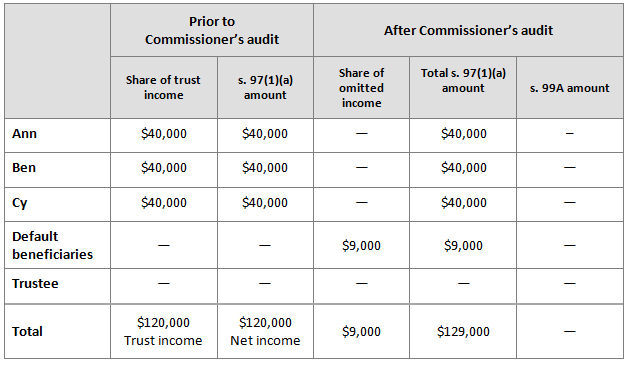

Assume the same facts as for Example 1, except that the trust deed provides that in the event of the trustee failing to appoint income by a particular time it is taken to be appointed to certain beneficiaries (commonly referred to as default beneficiaries).

In this case, the $9,000 would be assessed proportionately to those default beneficiaries as shown in the table below.

Assume the same facts as for Example 1, except that the trustee resolved to distribute $40,000 to each of Ann, Ben and Cy and the balance to David. On the basis of this resolution, the additional $9,000 net income would be assessed to David. Ann, Ben and Cy would each remain assessable to $40,000.

Assume the same facts as for Example 1, except that the trustee resolved to distribute one-third of the trust income to each of Ann, Ben and Cy.

On the basis of this resolution, each beneficiary is presently entitled to one-third of the trust’s income (being the same as the net income determined on audit). That is, each beneficiary is presently entitled to 1/3 × $129,000 = $43,000.

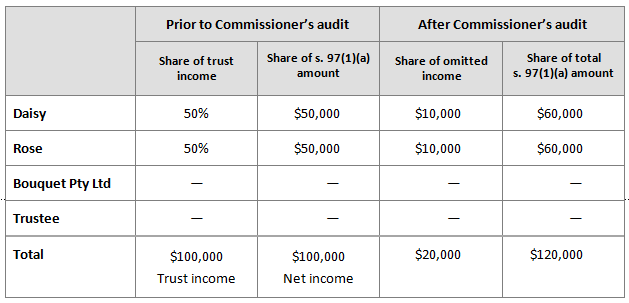

The table below shows the amounts that Daisy and Rose are each assessable on under the proportionate approach.

As the trustee’s resolution effectively dealt with all of the income of the trust by distributing the income to Daisy and Rosy equally, there was nothing in respect of which the further resolution in favour of Bouquet Pty Ltd could operate.

The outcomes from the above examples, and TD 2012/22 more generally, can be summarised as follows:

During the consultation for TD 2012/22, the wording of effective trustee resolutions were discussed by the NTLG Trust Consultation Subgroup. In the draft minutes of the 18 September 2012 meeting at item 6.2 the issue of formulaic resolutions was raised. For example are the following effective to confer present entitlement?

The ATO conceded that the first type of formulaic resolutions would generally be effective to create the purported entitlements, however, determined that they would not include an example in TD 2012/22 using such a resolution due to their ‘ostensible purpose of ensuring certain tax outcomes as opposed to particular trust entitlements’. Importantly however, this type of formulaic resolution may not direct any amendment to the net income to the desired beneficiary, unless there is a corresponding adjustment to the distributable income of the trust. A case on point is Donkin’s case discussed below.

Unsurprisingly the ATO does not generally accept resolutions of the second type as being effective to create a present entitlement to the income of the trust by 30 June.

The critical importance of understanding the trust deed and whether the wording of the trustee’s resolution is effective, particularly in the context of an amended assessment, was highlighted in the recent Tribunal case: Donkin & Ors and FCT (Donkin’s case).

In Donkin’s case, the trustee (using the first type of the above formulaic resolution) resolved that the trust’s distributable (trust law) income for the year should be distributed to each of the four individual beneficiaries in such amount as was required to equate to a specified amount of assessable income, for example in the 2012 income year:

Quoting paragraph 15 of the decision the definition of income was:

‘Income’ in respect of any Financial Year shall include so much of the receipt, profit or gain (or any part thereof) of the Trust Fund for the Financial Year which is assessable income for the purposes of the Tax Act that the Trustee in his discretion

(It should be noted the decision ended its extract of the definition there.)

So while the deed appeared to have an equalization clause of sorts, this definition of income effectively allowed the trustee, at his discretion, to include amounts in trust income which were assessable income for the purposes of the ITAA.

During the relevant years the trustee made a valid determination of income.

Interestingly, this determination of income did not have the effect of ensuring income of the trust was its s. 95 income, but instead it set income at an amount by reference to the taxable income ascertained by the trustee at the time. It was observed that this had ‘the effect of fixing the individual beneficiaries’ respective shares of net income as the proportion to which the specified amounts of “assessable income” bore to the trust’s s. 95 net income as ascertained by the trustee’. This is not the same as an equalisation clause that would increase distributable income if the taxable income was increased.

The Trust’s net income was increased and the Commissioner, relying on the decision in Bamford, issued amended assessments to, or for, the individual beneficiaries increasing their taxable incomes by amounts based on their share or percentage entitlement to the trust law income of the trust.

The Taxpayers contended that the effect of the resolutions was that the corporate residuary beneficiary was assessable to the increase in net income of the trust and that the amount of each individual beneficiary’s share of the net income remained constant.

The Tribunal accepted the Commissioner’s construction of the resolutions that the increase in the net income of the trust did not alter either the amount of or the entitlements to the distributable income.

The Tribunal found that the Commissioner was correct in his application of the decision in Bamford, and assessing the individual beneficiaries to the increased net income in the same proportions as he calculated they shared in the trust law income according to the resolutions.

Present entitlement to distributable income of the trust, or no present entitlement, determines where the liability for tax on the net income of the trust will fall. The interaction between the trust deed (in particular the definition of income) and the wording of the resolution will determine present entitlement.

The beneficiaries who are presently entitled to trust income will be liable for the tax on their corresponding proportion of the trust’s net income. If there is no one who is presently entitled to the trust income then it is the trustee who will be assessed.

Working backwards by first establishing the amount which we want to be taxed to a beneficiary — e.g. because the amount is under a threshold to which a lower rate of tax applies — may be effective to establish the proportion of the distributable income to which the beneficiary is presently entitled. Once that is established it will be applied to determining the share of net income which is assessable to the beneficiary. If the net income of the trust increases, this will not change the amount of or their shares of distributable income.

Understanding this interaction, and then carefully drafting the resolutions, will determine where the tax liability falls.

Interested in diving deeper into this topic? Check out our Special Topic presentation – Relevance of accounting for tax purposes.

Purchase the session or recording here:

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.