[print-me]

The highly anticipated measures that will prevent passive investment companies from accessing the lower corporate tax rate from 2017–18 were introduced into Parliament on 18 October 2017. The Bill proposes to improve the current law by setting a ‘bright line’ test to determine which companies are eligible for the tax cut. Clarity has finally trumped confusion.

[/fusion_text][fusion_table]

| Federal Budget 2016–17 announcement | |

| The Government announced its intention to progressively reduce the tax rate for all companies to 25 per cent by 2026–27 | Announced: 3 May 2016 |

| Corporate tax cuts and changes to the maximum franking credit calculation enacted | |

| Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan) Act 2017 | Became law: 19 May 2017 Date of effect: 1 July 2016 |

| Tax cuts for larger companies ≥ $50m — Bill before Parliament | |

| Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan No. 2) Bill 2017 | Introduced into Parliament: 11 May 2017 |

| ATO guidance on when a company is carrying on a business | |

| Reducing the corporate tax rate (QC 48880) | Published: 4 July 2017 |

| Government media release — passive investment companies | |

| Kelly O’Dwyer’s media release — clarified that the tax cut was not meant to apply to passive investment companies | Issued: 4 July 2017 |

| Exposure draft legislation — passive investment companies | |

| Eligibility for the lower company tax rate | Released: 18 September 2017 |

| Bill before Parliament — passive investment companies (base rate entities) | |

| Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan Base Rate Entities) Bill 2017 | Introduced into Parliament: 18 October 2017 |

| Draft taxation ruling — carrying on a business (base rate entities) | |

| TR 2017/D7 | Issued: 18 October 2017 |

[/fusion_table][fusion_text]

A series of corporate tax cuts, and a new method of calculating maximum franking credits which can be attached to a distribution, were legislated on 19 May 2017 although the measures have retrospective effect from 1 July 2016.

These new rules are briefly summarised below. Refer to our previous article The new franking conundrum for more detail.

The enacted legislation implements a series of corporate tax cuts from the 2016–17 to the 2026–27 income years. In the first stage of the plan, companies that carry on a business and have an aggregated turnover of less than $10 million for 2016–17 are entitled to the lower tax rate of 27.5 per cent. By 2026–27, all companies that carry on a business and have an aggregated turnover of less than $50 million will be permanently taxed at 25 per cent.

A company is eligible for the lower tax rate for an income year if it is:

A company is an SBE for the 2016–17 income year if:

Under the current law, from the 2017–18 income year, a company is a BRE for an income year if:

![]() Note

Note

The Government proposed the tax cuts in the 2016–17 Federal Budget. In the original 10-year Enterprise Tax Plan, tax cuts were to be progressively made available to all companies — regardless of turnover — and a flat 25 per cent corporate tax rate would apply permanently from 2026–27. However, the legislated tax cuts apply only to companies with an aggregated turnover of less than $50 million. On 11 May 2017, the Government tabled a Bill in Parliament which proposes to reduce the tax rate to 25 per cent by 2026–27 for all companies — i.e. to give full effect to the original proposal. At time of writing, the Bill was before the House of Representatives.

From 1 July 2016, the maximum franking credit is calculated by reference to its corporate tax rate for imputation purposes (CTRFIP). This may or may not be the same as its corporate tax rate.

The CTRFIP — a new concept that did not exist prior to 2016–17 — calculates the maximum franking rate that the company can frank a distribution that it makes to its shareholders. Broadly, a company’s CTRFIP is its corporate tax rate, using its previous year’s turnover as a proxy for the current year’s turnover. This addresses the dilemma where a company wants to make a franked distribution during an income year but is unable to determine its turnover — and therefore its corporate tax rate — until after the end of that income year.

A recurring question which underpins access to the tax cuts is: What is carrying on a business for the purposes of these rules?

To be an SBE or a BRE, and so qualify for the lower tax rates, a company must be carrying on a business for the relevant income year. That term is not defined in the tax law. While the requirement for an SBE to carry on a business is not new (the SBE definition has applied for small business concession purposes since 2007–08), the enactment of the tax cuts intensified demands for clarity and guidance on specific circumstances.

Specifically, the tax community has questioned whether the 27.5 per cent tax rate applies to holding companies, corporate beneficiaries and other ‘passive’ investment companies; in other words, whether any or all of these types of companies can be said to be ‘carrying on a business’.

In response, both the Government and the ATO made preliminary — and somewhat conflicting — comments in relation to this issue.

On 4 July 2017, the ATO published website guidance Reducing the corporate tax rate (QC 48880). The guidance states that:

… where a company is established and maintained to make profit for its shareholders, and invests its assets in gainful activities that have a prospect of profit, then it is likely to be carrying on business. This is so even if the company’s activities are relatively passive, and its activities consist of receiving rents or returns on its investments and distributing them to shareholders. [emphasis added]

(This guidance essentially replicates the position that the ATO previously — on 15 March 2017 — took in footnote 3 of draft ruling TR 2017/D2, which is concerned with the ‘central management and control’ limb of the statutory tax residency test for companies.)

The comments in Reducing the corporate tax rate, and the consequential widespread conclusion that a passive investment company can access the 27.5 per cent tax rate, elicited an adamant response by the Minister for Revenue and Financial Services, Kelly O’Dwyer. On the same day — 4 July 2017 — the Minister issued a media release clearly stating the Government’s policy intent that the tax cut ‘was not meant to apply to passive investment companies’.

On 18 September 2017, the Treasury released exposure draft legislation (the ED) to clarify that a company will not qualify for the lower corporate tax rate if most (at least 80 per cent) of its income is of a passive nature. The ED was met with widespread disapproval by the tax community. In addition to numerous technical deficiencies, the ED was heavily criticised for completely side-stepping the uncertainty surrounding the ‘carrying on a business’ requirement with no clarification in that respect. Further, the proposed retrospective application date of 1 July 2016 was particularly unwelcome as it would have resulted, in some cases, in amendments to lodged tax returns and payment of additional tax.

The Bill which was subsequently tabled in Parliament on 18 October 2017 (see below) thankfully differs significantly from the ED. While it retains the core passive income test that appeared in the ED, the technical redesign of the proposed measures has overcome a number of the identified deficiencies of the ED and overall provides some much-needed clarity on which companies will qualify for the lower tax rate from 2017–18.

The core purpose of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan Base Rate Entities) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to ensure that ‘passive investment companies’ will not be able to access the lower tax rate in a given income year; instead, they will be taxed at 30 per cent. As a fair corollary, these companies can frank distributions made in the following year at 30 per cent.

The Government’s term ‘passive investment company’ does not appear in the Bill but the concept is represented by a ‘bright line’ test. This test will deem a company to be ‘passive’ for a particular income year if more than 80 per cent of its assessable income comprises specific types of ‘passive’ income. The ‘bright line’ test has no regard for actual activity, intention, assets or profitability. Further, the Commissioner of Taxation has no discretion to grant an exception.

These amendments, if enacted in their current form, will have retrospective effect from 1 July 2017 (or the first day of a company’s 2017–18 income year if the company is a substituted accounting period taxpayer).

The Treasury heeded the tax community’s concern over the inherent uncertainty of the ‘carrying on a business’ requirement — in both the current law and the ED — to access the lower tax rate. In response, the Bill completely removes that uncertainty — by repealing the requirement in its entirety from the definition of a BRE.

It is proposed that the ‘carrying on a business’ test be replaced with a passive income test.

The Bill proposes that a company is a BRE if it satisfies two requirements:

The following types of income are BREPI:

The proposed passive income test requires a comparison of the company’s total BREPI for the income year to its assessable income for the income year. In contrast, the existing turnover test uses the company’s aggregated turnover.

Note the following key differences in relation to the income figures used in the two tests:

| Existing aggregated turnover test | Proposed passive income test |

| Grouping rules apply — the annual turnovers of entities connected with the company and its affiliates are aggregated with the company’s annual turnover | No grouping rules apply — the company’s BREPI and assessable income are measured on a standalone basis. Amounts derived by connected entities and affiliates are not taken into account |

| Aggregated turnover includes only ordinary income derived in the ordinary course of carrying on a business, with certain adjustments | Assessable income includes both ordinary income and statutory income |

The proposed passive income test is one of the two mandatory eligibility requirements for the lower tax rate. The company’s entire taxable income will be taxed at one rate, whether that be 27.5 per cent or 30 per cent. A company will never have its BREPI taxed at 30 per cent and its business income taxed at 27.5 per cent.

All rental income is taken to be BREPI. There is no carve-out for companies that derive rental income in the course of carrying on a business of renting properties. This is similar to the active asset test in s. 152-40(4)(e) of the ITAA 1997 which prevents assets whose main use is to derive rent from being an active asset.

Non-portfolio dividends are specifically excluded from being BREPI. A distribution is a non-portfolio dividend where the holding company holds at least 10 per cent of the voting power in the subsidiary. Therefore, distributions that holding companies receive from their subsidiaries are not BREPI.

As a general rule, from 2017–18, a holding company will be eligible for the 27.5 per cent tax rate if its aggregated turnover is less than the turnover threshold. Whether the holding company’s activities constitute ‘carrying on a business’ will no longer be a relevant consideration (although it remains relevant for 2016–17).

Where the holding company also holds assets from which BREPI is derived — most commonly interest-bearing deposits, rental properties and portfolio shares — care must be taken to ensure that its BREPI does not exceed 80 per cent of its assessable income (which includes the non-BREPI dividends received from its subsidiaries).

Under the proposed BREPI test, a trust distribution received by a corporate beneficiary must be dissected into its:

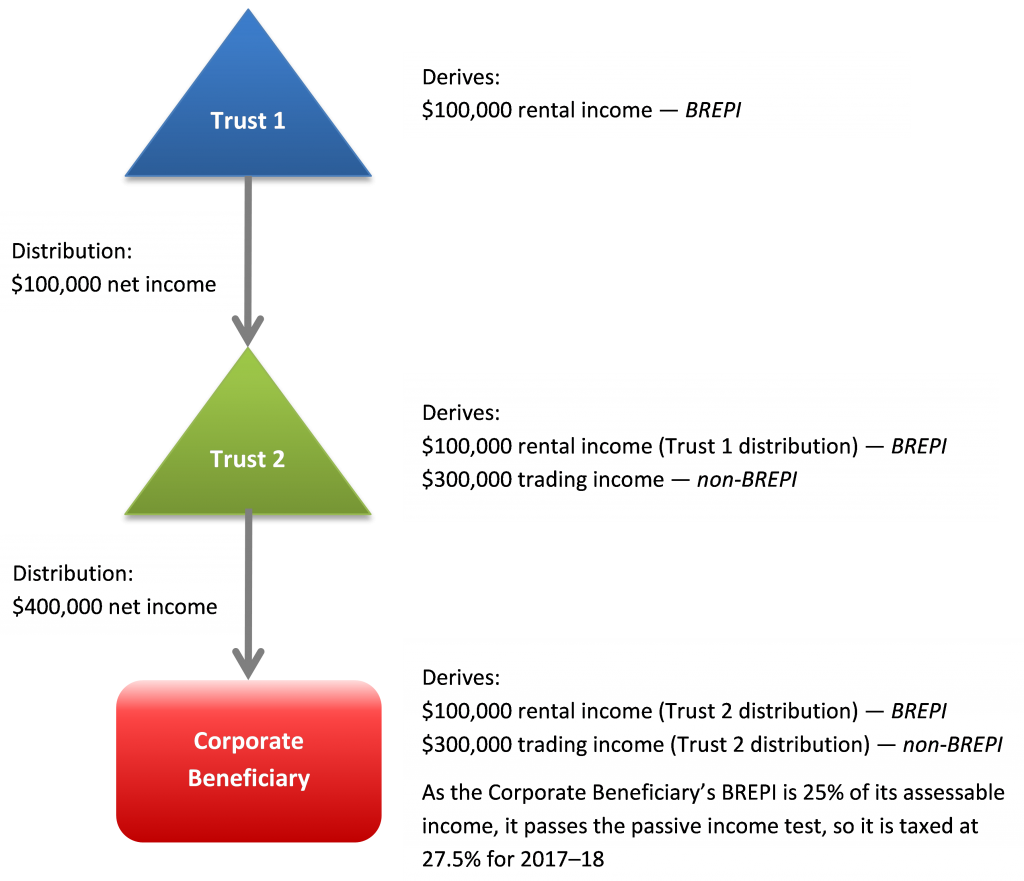

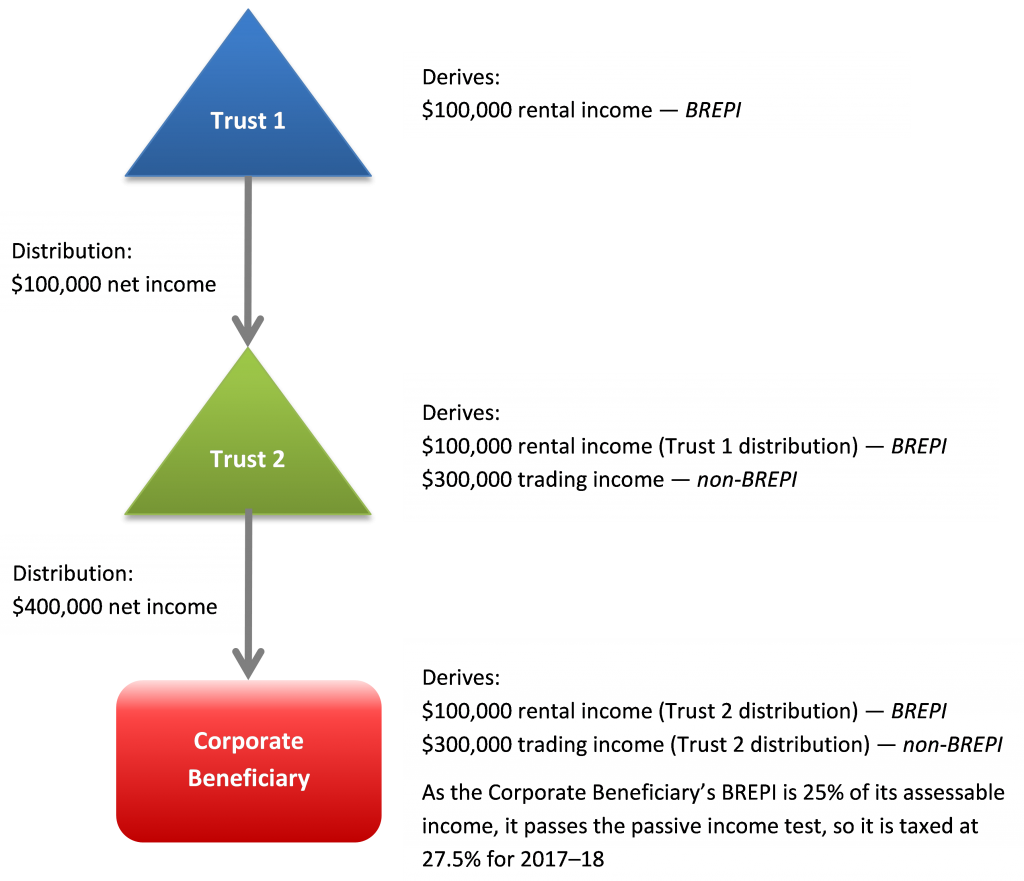

The Bill explicitly clarifies that income will retain its BREPI/non-BREPI character when it flows through a chain of trusts, for example:

In this illustration, the corporate beneficiary is taxed at the lower 27.5 per cent tax rate for 2017–18 as it satisfies both of the eligibility criteria to be a base rate entity:

| Passive income test | BREPI = 25 per cent of the company’s assessable income:

BREPI = $100,000 (i.e. attributable to rental income distributed from Trust 1 via Trust 2) Assessable income = $400,000 (i.e. Trust 2 distribution) The passive income test is satisfied as 25 per cent is not greater than 80 per cent |

| Aggregated turnover test | It is assumed that the corporate beneficiary’s aggregated turnover — including the turnovers of any connected entities and affiliates — is less than $25 million in 2017–18 |

Implications

Implications

In relation to trust distributions, the tax law only recognises the streaming of net capital gains and franked distributions to beneficiaries. Other classes of income cannot be separated and distributed to different beneficiaries. However, the manner in which capital gains and franked distributions are distributed to beneficiaries may affect whether a corporate beneficiary satisfies the proposed passive income test.

Further, the corporate beneficiary will need to trace up through a chain of one or more interposed partnerships or trust estates to determine the extent to which the distribution is attributable or not to BREPI. Perhaps new labels which identify the amount of BREPI included in a partnership or trust distribution will appear in the 2018 tax returns so that the ultimate corporate beneficiary can calculate its BREPI as a proportion of its total assessable income for an income year.

The Bill proposes to amend the CTRFIP rules so that it is assumed that the passive income proportion for the current year is equal to that of the previous year in determining the maximum franking rate.From 2017–18, a company’s CTRFIP for an income year will be equal to its corporate tax rate for that income year with the following assumptions:

If the previous year’s BREPI was at least 80 per cent of the company’s previous year’s assessable income, the company’s maximum franking rate for the current year is 30 per cent — regardless of its aggregated turnover or whether it is carrying on a business. Incidentally, the corporate tax rate for the previous year would also have been 30 per cent.

The following table summarises the different corporate tax rates and maximum franking rates that apply under the Bill:

| Corporate tax rate | Maximum franking rate | |

| Base rate entity

In the current income year:

|

27.5% | In the previous income year:

|

| Not a Base rate entity

In the current income year:

|

30% | In the previous income year:

|

The headline proposal in the Bill is the repeal of the ‘carrying on a business’ condition to access the lower tax rate from 2017–18.

On 18 October 2017 — the same day on which the Bill was introduced into Parliament — the ATO issued draft taxation ruling TR 2017/D7 which sets out the Commissioner’s preliminary views in relation to when a company carries on a business for the purposes of the definition of a BRE. The draft ruling states that:

… where a … company is established and maintained to make a profit for its shareholders, and invests its assets in gainful activities that have both a purpose and prospect of profit, it is likely to be carrying on a business in a general sense and therefore to be carrying on a business within the meaning of [a BRE] … This is so even if the company’s activities are relatively limited, and its activities primarily consist of passively receiving rent or returns on its investments and distributing them to its shareholders.

This position reflects the broad view expressed in the initial guidance provided on 4 July 2017 (see above). The draft ruling provides eight practical examples, including scenarios involving corporate beneficiaries with unpaid present entitlements (UPEs) and holding companies.

Example 5 sets out various scenarios in relation to whether corporate beneficiaries that have UPEs to a share of trust income are considered to be carrying on a business. Remarkably, the Commissioner’s preliminary view in one of the scenarios is that because the activities of a corporate beneficiary that reinvests its UPE consist of investing its assets in a business like way with both a purpose and prospect of profit, the Commissioner concludes that the company is carrying on a business. Notably, this draft ruling applies only for the purpose of the BRE definition and therefore only from 1 July 2017. But this has led some practitioners to conclude that there will be corporate beneficiaries that have lodged their 2016 and/or 2017 tax returns — on the basis that they were not eligible for the lower tax rate, and so determined that their tax rate was 30 per cent — that may seek an amendment on the basis they are eligible for the lower tax rate and claim a refund of overpaid tax.

If the Bill is enacted in its current form, we expect that this draft ruling would not be finalised or could even be withdrawn as the ‘carrying on a business’ requirement will be removed from the definition of a BRE.

The amendments proposed in the Bill do not affect the definition of an SBE. Therefore the ‘carrying on a business’ condition is still relevant for 2016–17 for companies determining whether they are an SBE and therefore eligible for the 27.5 per cent rate in that income year.

Critical Point

Critical Point

The scope of the draft ruling is limited to what constitutes carrying on a business for the purposes of satisfying the definition of a BRE, which takes effect from 2017–18. The scope of the draft ruling does not extend to any other provision in the tax law. Relevantly, it is not intended to apply to the ‘carrying on a business’ requirement in the definition of an SBE. Therefore, taxpayers and advisers cannot rely on this draft ruling to determine whether a company is eligible for the 27.5 per cent tax rate in 2016–17.

Comment

Comment

The BRE definition was based on the SBE definition, and the requirement that a company carry on a business is common to both concepts (under the current law). Accordingly, it is intriguing that the Commissioner’s preliminary view on whether a company is carrying on a business is confined to BRE purposes and does not also apply for SBE purposes. It is difficult to see how the term ‘carries on a business’ could mean one thing for BRE purposes but another for SBE purposes. Practically, despite the Commissioner’s clear statement that the draft ruling applies only for BRE purposes, it is foreseeable that many practitioners will nonetheless also apply the Commissioner’s preliminary views for SBE purposes.

We keenly await whether the Bill will be enacted in its current form. The proposed amendments, if legislated, will bring much needed clarity around eligibility for the tax cuts from 2017–18. A law that is simpler to understand will also improve taxpayer compliance rates and reduce inadvertent errors.

The ‘carrying on a business’ confusion still exists in relation to 2016–17, so we are not out of the woods yet. We are hopeful for some definitive guidance on this front from the ATO for corporate taxpayers and their tax agents currently completing 2017 tax returns — perhaps the ATO will alter the draft ruling and extend its application to also cover the meaning of an SBE.

If the enacted and proposed amendments to the corporate tax rate and the franking implications are extended to those companies with a turnover of $50 million or more, then the issues that are currently tying the SME sector up in knots as it works through the complicated changes will also become the domain of the large corporate sector.

Click to see infographic: The history of Australia’s company tax and dividend imputation systems:

Contact Taxbanter to discuss your 2018 tax training needs: 03 9660 3500 | enquiries@taxbanter.com.au

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.