A key module in TaxBanter’s Tax Fundamentals program is Capital Allowances. There is an array of different thresholds, applicable dates, calculation methods and hidden peculiarities throughout the provisions. Given depreciation deductions are as relevant to large companies as they are to salary and wage earners, an understanding of the legislative intricacies is imperative for every tax practitioner.

Some of these tricks, traps and quirky aspects are outlined below.

From the outset, a deduction for depreciation is complicated by the fact that, for small business entities (SBEs), there are two sets of legislative provisions that could apply. Accordingly the starting point for a depreciation deduction is to determine which legislative path to take: head down the traditional path of Div 40 of the ITAA 1997, or venture down the ever-expanding and mostly more generous road of Div 328 of the ITAA 1997? The answer depends on both the type of taxpayer and the category of asset.

| Div 40 | Div 328 | |

| Taxpayer | Individual not in business

SBE who has not chosen Div 328 Non-SBE |

SBE who has chosen Div 328 |

| Asset | All eligible assets except for the following exclusions, even where an SBE has chosen Div 328:

|

All eligible assets owned by an SBE who has chosen Div 328, even if the asset is not used in the business of the SBE |

In 2001 when the New Business Tax System (Capital Allowances) Bill 2001 was introduced into Parliament, the Explanatory Memorandum promised ‘a uniform capital allowance system that will offer significant simplification benefits’. That may have been forgotten over time as the combination of Divs 40 and 328, as well as the ATO’s administrative practice, has resulted in seven different cost thresholds.

| Asset cost | Asset type | Treatment | Details |

| <$100 | Business assets | Immediately deductible | The ATO considers this to be revenue expenditure — see PS LA 2003/8.

Not available to entities using Div 328. This is the only threshold that is GST-inclusive. |

| ≤$300 | Non-business assets | Immediately deductible | Section 40-80(2) allows an immediate deduction of non-business assets costing no more than $300.

The asset cannot be part of a set of assets, or part of a group of identical assets, costing more than $300. However, if the asset is jointly held with others but the cost of the taxpayer’s interest in the asset is $300 or less, an immediate deduction is available even where the total cost of the asset exceeds $300. |

| <$1,000 | Assets not subject to simplified depreciation rules in Div 328 | Add to a low-value pool and depreciate at:

|

Section 40-425 allows a taxpayer to establish a low-value pool (if they choose) where all acquisitions of low-value assets will then be added to the pool and deducted on a pooled basis.

The termination value of any asset sold reduces the closing pool balance, but not to below zero. If the termination value of the asset exceeds the closing pool balance, the excess is assessable income. |

| The instant asset write-off | |||

| <$1,000 | Assets subject to simplified depreciation rules in Div 328 | Immediately deductible | Available for:

|

| <$20,000 | Assets subject to simplified depreciation rules in Div 328 | Immediately deductible | Available for assets acquired on or after 7.30 pm on 12 May 2015 but before 1 July 2020; where the asset is first used, or installed ready for use from 7.30 pm on 12 May 2015 to 28 January 2019 |

| <$25,000 | Assets subject to simplified depreciation rules in Div 328 | Immediately deductible | Available for assets acquired on or after 7.30 pm on 12 May 2015 but before 1 July 2020; where the asset is first used, or installed ready for use from 29 January 2019 to 7.30 pm on 2 April 2019 |

| <$30,000 | Assets subject to SBE rules and

Asset of medium sized businesses |

Immediately deductible | SBEs — available for assets acquired on or after 7.30 pm on 12 May 2015 but before 1 July 2020; where the asset is first used, or installed ready for use from 7.30 pm on 2 April 2019 to 30 June 2020

Medium sized businesses — available for assets acquired and used, or installed ready for use from 7.30 pm on 2 April 2019 to 30 June 2020 |

![]() Medium-sized businesses — a special case

Medium-sized businesses — a special case

For a medium sized business (i.e. a business with an annual aggregated turnover of at least $10 million and less than $50 million) a transitional rule effectively gives them access to the instant asset write-off for assets costing less than $30,000 until 30 June 2020. Interestingly this transitional rule must be applied; these taxpayers cannot choose whether to write off eligible assets. See the Banter Blog article New instant asset write-off from 11 April 2019 for more detail.

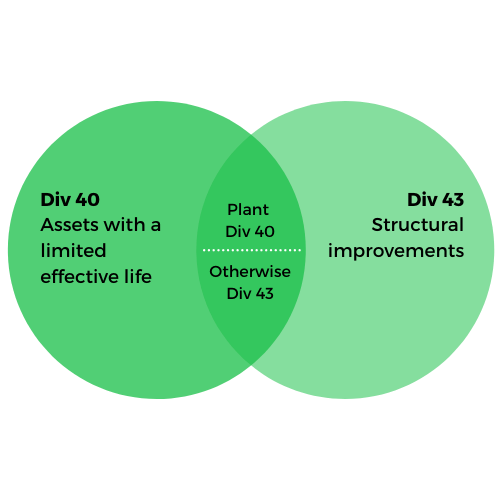

When looking for tax recognition for expenditure on an asset, especially in the context of an income-producing rental property, determining whether the asset’s cost is depreciable under Div 40, or alternatively written off under the capital works provisions of Div 43 of the ITAA 1997 can be tricky.

A depreciating asset is defined as an asset with a limited effective life that is reasonably expected to decline in value over time. Capital works includes structural improvements alterations and other improvements. As such, some items of expenditure may fall within both definitions. Where the expenditure meets both definitions, to the extent it meets the definition of ‘plant’, the expenditure is depreciated under Div 40. Otherwise Div 43 takes precedence.

In identifying what constitutes plant, the courts have adopted a ‘functional test’ based on the function that the item performs in the taxpayer’s income-earning activity. That is, if the item:

The rental property will almost always be the setting within which the landlord derives assessable income.1 The extent to which an item that forms part of the premises constitutes plant which is a depreciating asset will be a question of fact and degree.

The Commissioner has identified the following matters as relevant to determining whether an item is plant in residential property:

The term ‘plant’, although not used in Div 40, is defined in s. 45-40 to include (relevantly):

…)

Relevant guidance from TR 2004/16 on the general principles established by the courts relating to the meaning of the terms ‘articles’ and ‘machinery’ is as follows:

| Articles | Machinery |

| The term takes its ordinary meaning — i.e. a piece of goods or property. It can include a carpet, a curtain, a desk, a bookshelf.

An item cannot be an article if it is attached to land. An item can be an article even if it is attached to a building. An item that forms an integral part of the fabric of the building is not an article. |

Machinery is plant whether or not it forms an integral part of a building or is part of the setting of the particular taxpayer’s income-earning activities.

The process of working out whether something is machinery, and therefore plant for the purposes of Div 40, involves:

|

The ATO document Rental properties 2019 contains a number of useful tables that classify residential rental property items as either depreciating assets or capital works. The following table contains examples of some of these items.

| Item in the rental property | Depreciating asset | Capital works |

| Kitchen cupboards (built-in) | ||

| Stoves, ovens and range hoods | ||

| Carpets and other floor coverings that are removable without damage (e.g. floating timber) | ||

| Bathroom fixtures e.g. bath, tapware, toilets, vanity units and wash basins | ||

| Heaters (not ducts, pipes, vents and wiring or fire places) | ||

| Window curtains and blinds (not awnings, insect screens, louvers, pelmets and tracks) | ||

| Solar hot water system (excluding piping) | ||

| Fixed television antennas | ||

| Security doors and screens (permanently fixed) | ||

| Automatic garage doors (excluding controls and motors) | ||

| Fences and retaining walls | ||

| In-ground swimming pool |

![]() Important

Important

From 1 July 2017, individuals (and some other entities) not carrying on a business, are unable to claim depreciation for assets in residential rental properties if they did not hold the asset when it was first used or installed ready for use (consequential changes mean that instead of a balancing adjustment on disposal, a capital gain or loss may arise under CGT event K7).

Transitional rules apply for certain assets acquired prior to 9 May 2017.

One of the interesting things about depreciation is that a seemingly common and relatively simple situation can raise a number of issues. Take the following common example:

On 1 November 2018, Sebastian purchased a new top-of-the-line dual cab ute. After much negotiation, he secured a changeover price for the vehicle of $40,000 by offering his current car as a trade-in. The new car sales contract showed a sales price of $60,000 for the new vehicle and an allowance of $20,000 for the trade-in. Shortly after taking delivery of the new vehicle, Sebastian added various accessories including a tow bar, driving lights and a bull bar. The cost of these items totalled $10,000.

In the 2018–19 income year, Sebastian did not use either his new vehicle or the previous car for work-related purposes.

However, during 2019–20, Sebastian’s employment role changed and he began to use the vehicle for income-producing purposes. Accordingly, he kept a logbook showing a 75 per cent business use.

The cost of a depreciating asset consists of two elements which comprise expenses that the taxpayer has incurred:

The first element includes amounts that a taxpayer is taken to have paid; this would include the trade-in value. As such, Sebastian’s first element of cost would be the changeover price plus the market value of the trade-in, namely $60,000 (i.e. $40,000 + $20,000).

The second element of a depreciating asset’s cost is essentially what is paid for economic benefits that contribute to the asset’s present condition and location. This is worked out after the taxpayer starts to hold the asset. In this case $10,000 has been spent on the various accessories. Therefore, a consideration of whether these composite assets are a depreciating asset in their own right, or part of the car, is needed.

TR 2017/D1 outlines some of the main principles to take into account in determining whether a composite item part of a single depreciating asset or is a separate asset. These factors include:

Arguably the accessories are part of the vehicle and would form second element of cost. In any event, this possibly is the better outcome as the inclusion of these items as part of the cost of the car would result in them being depreciated using the effective life of a car, namely eight years (noting that none of these items are separately listed in the ATO’s effective life ruling).

Another consideration with respect to the cost of the car is the car cost limit. Section 40-230 restricts the first element of the cost of a car to the relevant car limit for the financial year in which the car is first held. The car limit for the 2018–19 financial year is $57,581 (this is also the limit for 2019–20). Consequently, the first element of cost for Sebastian’s car is limited to $57,581.

Notably this limit does not impact the second element of cost.

The total cost for the car is therefore $67,581.

A depreciating asset starts to decline in value from when its ‘start time’ occurs. The start time is when the taxpayer first uses the asset or has it installed ready for use for any purpose. In this case the start time is 1 November 2018. This may impact the choice of method.

A taxpayer generally may choose either the diminishing value (DV) or prime cost (PC) method. The decline in value under both methods is calculated below to see which option is better for Sebastian.

2018–19 income year

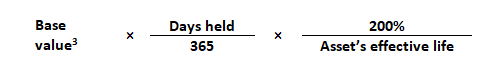

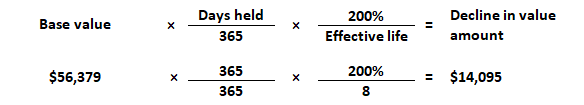

The formula for working out the decline in value for the car under the DV method is:

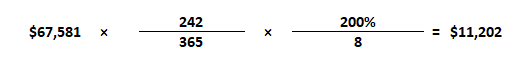

Although the car has declined in value during the 2018–19 income year, Sebastian has not been using it for a taxable purpose. Therefore, no deduction is available.The decline in value for the car is:

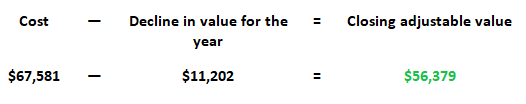

The adjustable value at the end of the 2018–19 income year — i.e. the first year — is however still reduced by the total decline in value of the asset and therefore is:

The closing adjustable value becomes the asset’s opening adjustable value in the next year.

2019–20 income year

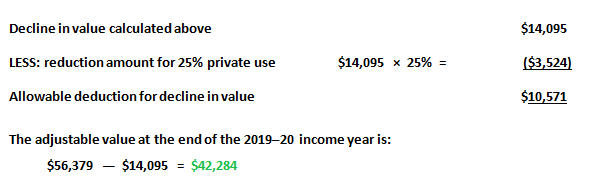

The decline in value for the car is:

The base value in the second and subsequent year is its opening adjustable value for that year plus any amount included in the second element of its cost for that year.

As the car is used 75 per cent for a taxable purpose, the decline in value must be reduced by 25 per cent. Thus, the deduction Sebastian can claim is:

2018–19 income year

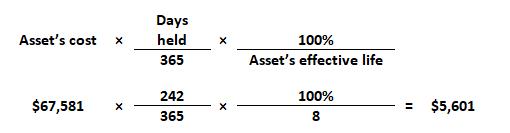

The decline in value for the car under the PC method is:

Although the car has declined in value during the 2018–19 income year, Sebastian has not been using it for a taxable purpose. Therefore no deduction is available.

The adjustable value, however, at the end of the 2018–19 income year is:

$67,581 — $5,601= $61,980

2019–20 income year

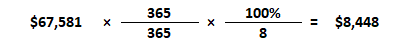

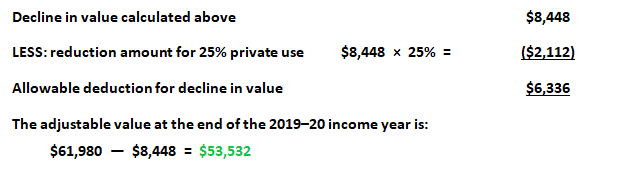

The decline in value for the car is:

As the car is used 75 per cent for a taxable purpose, the decline in value must be reduced by 25 per cent. Thus, the deduction Sebastian can claim is:

While the DV method will give Sebastian a greater deduction in the 2019–20 year ($10,571 compared with $6,336 for the PC method), the DV method results in a greater decline in value in the 2018–19 income year for which no depreciation can be claimed as a deduction (i.e. the decline in value under the diminishing value method for 2018–19 is $11,202 compared with $5,601 under the PC method).

The choice of method therefore will require a consideration of how long Sebastian expects to both hold and use the car.

1 Paragraph 12 of TR 2004/16.

2 Paragraph 13 of TR 2004/16. Note that TR 2007/9 provides guidance on when an item used to create a particular atmosphere or ambience for premises used in a cafe, restaurant, licensed club, hotel, motel or retail shopping business constitutes an item of plant.

3 In the first year this is equal to the cost of the car as determined by applying the adjustment for the car limit.

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.