Some movement on Div 7A … at last!

On 22 October 2018, the Treasury released a consultation paper titled Targeted amendments to the Division 7A integrity rules. The paper sets out the Government’s proposed implementation of the amendments to improve the integrity and operation of Div 7A of Part III of the ITAA 1936 (‘Div 7A’), and seeks submissions from interested parties by 21 November 2018. The outcome of this consultation will assist in the development of legislation required to implement the measures.

Background

On 18 May 2012, the then Assistant Treasurer and Minister assisting for Deregulation, David Bradbury, announced that the Board of Taxation (‘the Board’) would undertake a post-implementation review of Div 7A.

The Board provided their final report to the Government on 12 November 2014, following the release of two interim discussion papers. The report, containing 15 recommendations, was released by the Government on 4 June 2015. But it wasn’t until 3 May 2016, as part of the 2016–17 Federal Budget, that the Government provided its response to that report.

Announcement in 2016–17 Federal Budget

In just a few paragraphs on page 42 of Budget Paper No. 2, under the heading Ten Year Enterprise Tax Plan — targeted amendments to Division 7A, the then Treasurer, Scott Morrison, announced that the Government would make targeted amendments to improve the operation and administration of Div 7A, drawing upon a number of recommendations from the Board’s post-implementation review of Div 7A.

The amendments were proposed to commence on 1 July 2018 and included:

- a self-correction mechanism for inadvertent breaches of Div 7A;

- appropriate safe harbour rules to provide certainty;

- simplified Div 7A loan arrangements; and

- a number of technical adjustments to improve the operation of Div 7A and provide increased certainty for taxpayers.

Announcement in 2018–19 Federal Budget

As we rapidly approached the proposed start date of 1 July 2018 earlier this year, there was still no sign of any detail on the proposed measures. So it was not unexpected that on 8 May 2018, as part of the 2018–19 Federal Budget, the then Treasurer, Scott Morrison, announced that the Government would defer the start date of the proposed targeted amendments to Div 7A that were announced in the 2016–17 Budget from 1 July 2018 to 1 July 2019.

In addition to the above four previously announced reforms, the Government also announced that unpaid present entitlements (UPEs) will come within the scope of Div 7A from 1 July 2019. This will apply where a related private company is made presently entitled to a share of trust income as a beneficiary but has not been paid that amount. This measure will require that the UPE is either repaid to the company, managed as a complying loan or subject to tax as a dividend.

This would enable all of the Div 7A amendments to be progressed as part of a consolidated package. It is noted in the consultation paper that the ATO will need to provide online tools and administrative guidance to educate taxpayers on the new rules.

So … this will be 7 years in the making, and that assumes that there is no further deferral of the start date beyond 1 July 2019 (which happens to fall right in the middle of an election year).

So, what is the detail of the new measures?

The proposed amendments can be categorised into the following five headings:

- Simplified loan rules;

- Unpaid present entitlements;

- Reviewing breaches of Div 7A;

- Safe harbours — provision of assets for use; and

- Minor technical amendments.

![]() Note

Note

This article does not purport to be a substitute for comprehensive training materials or provide a comprehensive analysis of the proposed legislative changes. Rather, it provides an overview of the Government’s position and intended policy on Div 7A from 1 July 2019.

Further, this article presumes that readers are familiar with the current law, so the existing position on each measure is not set out for context.

1. Simplified loan rules

Under the proposed measures, a new 10-year loan model will be implemented for complying Div 7A loans. The key aspects of these new rules are set out in the table below.

| Issue | Discussion |

| Single 10-year loan model | The current 7-year and 25-year loan models will be replaced by a single loan model with the following features:

This model is intended to be simpler than the current model for apportioning repayments between principal and interest and better aligned to commercial practice for principal and interest loans. |

| Transitional rules for existing loans | All complying 7-year loans that exist as at 30 June 2019 must comply with the proposed new loan model and benchmark interest rate to remain complying but will retain their existing outstanding term. Current loan agreements which refer to the benchmark interest rate should not require renegotiation.

All complying 25-year loans that exist as at 30 June 2019 will be exempt from the majority of the changes until 30 June 2021, however the new benchmark interest rate will need to be applied. While the consultation paper states that a complying loan agreement will need to be put in place before lodgment of the company’s 2020–21 tax return, it is not clear whether the term under that agreement would be a new 10-year term or the remaining part of the existing 25-year term. All pre-4 December 1997 loans (i.e. loans which predate the commencement of Div 7A) will be taken to be financial accommodation as at 30 June 2021 (i.e. a two-year transitional period from 1 July 2019). The loan will need to be repaid in full or managed as a complying loan with a 10-year term by the lodgment day of the company’s 2020–21 tax return, otherwise the loan will be deemed a dividend in the 2020–21 income year. The first repayment under a complying loan arrangement would be due by 30 June 2022. |

| Distributable surplus | Instead of limiting the amount of a deemed dividend to an arbitrarily determined amount — and thereby limiting the amount taxed — the concept of ‘distributable surplus’ will be removed and the amount that can be deemed a dividend will be based on the entire value of the benefit that was extracted from the company.

This measure will also align the tax treatment of Div 7A dividends with the corporations law which allows dividends to be paid out of profits and capital. |

![]() Note

Note

There has been ongoing uncertainty about the application of Div 7A to non-resident private companies in certain circumstances, for example, whether it applies where the shareholder is also a non-resident, issues of ‘source’ and how Div 7A interacts with the transfer pricing rules and double tax treaties. The Government seeks feedback on the extent of any uncertainty and how best to remove any such uncertainty.

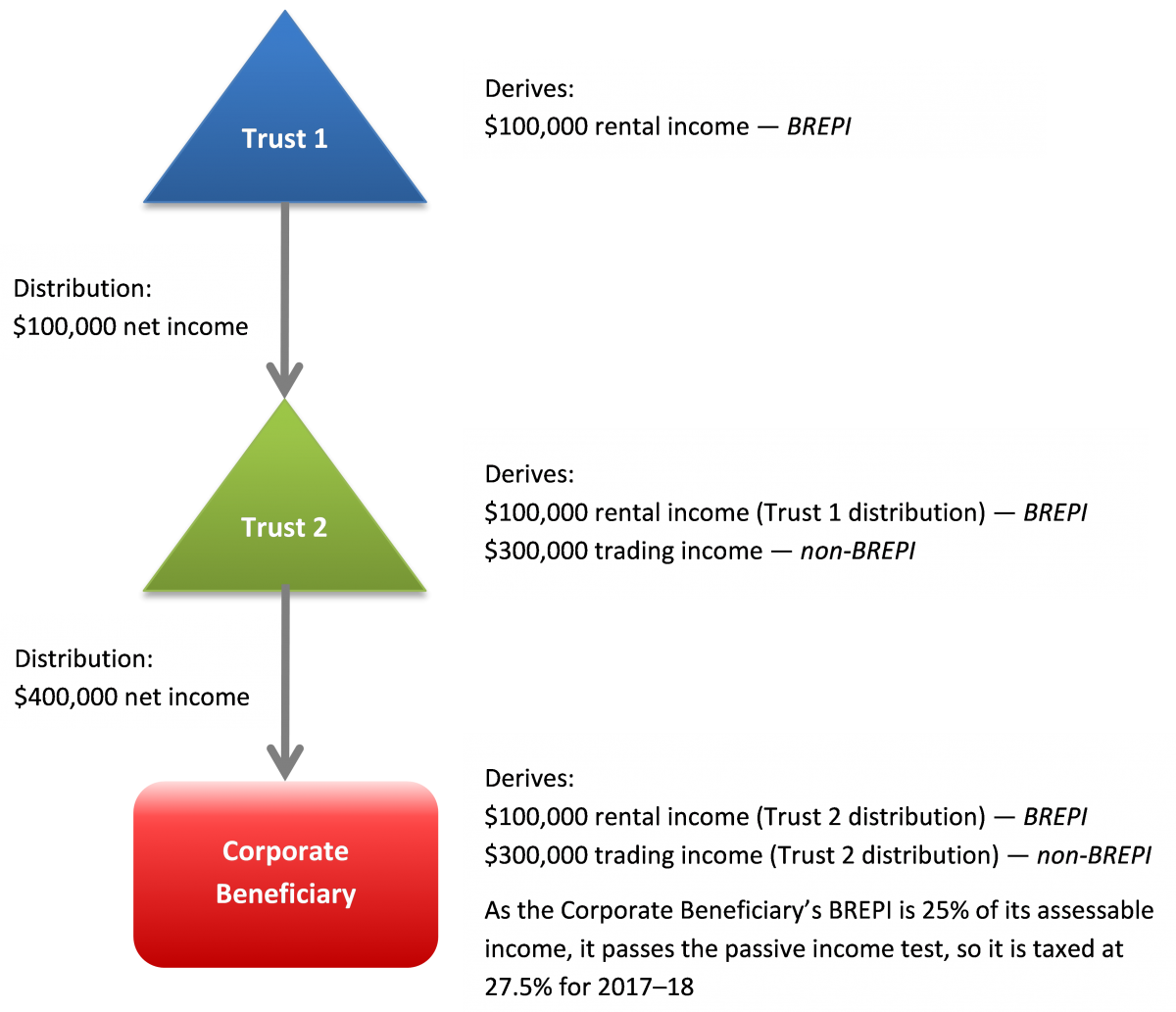

2. Unpaid present entitlements

Under the proposed measures, where a UPE remains unpaid at the lodgment day of the company’s tax return, broadly from 1 July 2019, the UPE will be a deemed dividend from the company to the trust. Alternatively, the UPE can be managed as a complying loan.

| Date on which UPE arises | Discussion |

| On or after 16 December 2009, and on or before 30 June 2019 | Those UPEs that have not already been put on complying loan terms or deemed to be a dividend will need to be put on complying loan terms by 30 June 2020 (the first repayment would be due in 2019–20).

The amount of any outstanding UPEs that are not put on complying loan terms by 30 June 2020 will be deemed a dividend. |

| On or after 1 July 2019 | These UPEs will need to be either paid to the company or put on complying loan terms under the new 10-year loan model prior to the company’s lodgment day, otherwise they will be deemed a dividend. |

| Existing UPEs that are already on complying loan terms | These UPEs will be treated in accordance with the relevant 7-year or 25-year loan transitional rules (see above). |

| Before 16 December 2009 | The Government is seeking feedback on whether these UPEs should be brought within Div 7A. Interestingly, there is not a definite position to put quarantined UPEs on complying loan terms at this time. |

3. Reviewing breaches of Div 7A

Self-correction mechanism

Taxpayers will be able to self-assess their eligibility for relief from Div 7A which will reverse the effect of a prior deemed dividend (replacing the current mechanism in s. 109R which requires taxpayers to apply for the Commissioner’s discretion to disregard a deemed dividend) without penalty. Only taxpayers who meet eligibility criteria will qualify for the self-correction relief.

Appropriate corrective steps must be taken within six months of identifying the error.

The current discretion in s. 109R will broadly be removed and will only be available where the taxpayer seeks the Commissioner’s discretion.

Period of review

Addressing concerns that taxpayers have claimed the Commissioner is out of time to amend the relevant return to include a deemed dividend that arose outside the amendment period, it is proposed that a new 14-year review period will apply to Div 7A transactions from 1 July 2019.

The review period will cover 14 years after the end of the income year in which a deemed dividend arises or would arise. It is expected that the new 14-year review period would apply to Div 7A transactions happening from 1 July 2019, but this is not explicitly stated in the consultation paper.

4. Safe harbours — provision of assets for use

Since the introduction of s. 109CA (about the use of company assets), it has been difficult to determine the arm’s length value of the use of an asset.

It is proposed that a safe harbour be introduced in the form of a legislative formula which would apply a benchmark interest rate to the value of the asset (as at 30 June for the year in which the asset was used). Taxpayers would still be able to calculate their own arm’s length value instead of applying the legislative formula. The safe harbour will apply for the exclusive use of all assets except motor vehicles.

5. Minor technical amendments

The consultation paper includes a number of proposed changes to improve the integrity and operation of Div 7A while increasing certainty.

These measures include:

- new timing rules on the use of company assets in the case of non-exclusive rights (e.g. where the company maintains a right to use the asset);

- modifying s. 109G(3) to ensure that the existing exclusion — that a forgiven debt will not be deemed a dividend if the loan that resulted in the debt gave rise to a deemed dividend under s. 109D — will only be available where the earlier dividend that the company was taken to have paid has been taken into account in the income tax assessment of an entity;

- modifying s. 109M to ensure that the existing exclusion for loans made in the ordinary course of a business is limited to loans made in the ordinary course of a business of money-lending to third parties, rather than in the ordinary course of any business;

- modifying s. 109T so that the interposed entity rule can apply even where the quantum or nature of the benefit provided to the taxpayer differs from the benefit provided to the interposed entity;

- modifying s. 109Z to make it clear that a payment that is deemed to be a dividend under Div 7A is not deductible; and

- amendments to improve the clarity and interaction between Div 7A and the FBT provisions.

Observations

It is disappointing that the ‘business income election’ model proposed by the Board of Taxation in its 2014 report — which would allow a trust to make a one-off election to distribute to a company or receive a loan from a company without a Div 7A consequence, but would forgo the CGT discount other than for goodwill as a recompense — is not mentioned in the Consultation Paper.

It is also disappointing that the Government has not taken the opportunity and sought to include an ‘otherwise deductible rule’ for loans made for genuine income-producing purposes, such as funds lent by a company to a trust to buy premises from which the company operates its business. This feature which exists in the FBT provisions is glaringly absent from the Div 7A provisions.

Further remarks by TaxBanter may be found in the following Accountants Daily article: Details on Division 7A changes released, welcomed

Where to from here?

Considerations for taxpayers

Taxpayers will need to consider:

- their previously quarantined pre-4 December 1997 loans being freshened up;

- whether they should enter into 25-year secured loans now, mindful of the falling property market;

- the impact of the changes on their post-16 December 2009 UPEs;

- the impact of the new 14-year amendment period;

- that the calculations of loan repayments and the amount of a deemed dividend will change, particularly with the proposed removal of the concept of the distributable surplus; and

- whether they would be eligible for self-correction relief where a deemed dividend has arisen.

Timing of policy development

Timing is critical: submissions are due by 21 November 2018, so it is unlikely we would see any draft legislation before Christmas. So that leaves around 5 months (ignoring January) for the Government to release draft legislation, further consult, introduce the amending Bill, secure the numbers in the Senate and enact the Bill before 1 July 2019 … and this is without factoring in the release of the Federal Budget and the next Federal Election. Although it is pleasing to see some detail on the new rules, until this is bedded down by way of enacted Bill, there will be ongoing uncertainty re: the impact of these proposed measures on taxpayers.

Submission

TaxBanter will be making a submission on the proposed changes to Div 7A. We invite you email us with any issues which should be considered for inclusion in our submission. Please email: enquiries@taxbanter.com.au by Wednesday 7 November 2018.

Consultation questions included in the paper

The consultation paper contains six consultation questions, comprising of 23 sub-questions. These are set out below.

| Issue | Question | |

| Discussion Question 1 | ||

| Proposed loan model | Is there an aspect of the proposed loan model that could be refined? | |

| Transitional rules | Do the proposed transitional rules result in any unintended outcomes? | |

| Application to non-resident private companies | In what circumstances (if any) is the application of Div 7A to non-resident private companies unclear? | |

| Would the application of Div 7A to non-resident private companies benefit from additional public guidance material? | ||

| Are legislative amendments required to clarify the application of Div 7A to non-resident private companies? | ||

| Distributable surplus | Does the removal of the concept of distributable surplus result in any unintended outcomes? | |

| If this concept is removed, are there any interactions with other provisions of Div 7A that might become relevant? | ||

| Discussion Question 2 | ||

| Unpaid present entitlements | Are transitional rules required for UPEs arising on, or after, 16 December 2009 and on or before, 30 June 2019 where the funds in the sub-trust are invested in the main trust using one of the investment options in PSLA 2010/4 and therefore the UPE is considered to be held for the sole benefit of the private company beneficiary? If so, what kind of transitional rules might be required? | |

| Should UPEs arising prior to 16 December 2009 be brought within Div 7A? | ||

| Discussion Question 3 | ||

| Self-correction mechanism | Are the eligibility criteria clear and concise? | |

| Are additional objective factors necessary to include in determining a taxpayer’s eligibility? | ||

| What guidance should be provided to assist taxpayers in using the self-correction mechanism? | ||

| Period of review | Will the period of review cause any unintended outcomes? | |

| Are there any alternative options to a 14-year review period that would ensure the integrity of the revised Div 7A? | ||

| Discussion Question 4 | ||

| Safe harbours – provision of assets for use | Is there an alternative formula which could be used? | |

| Should taxpayers have the option to elect between the statutory formula and providing their own arm’s length usage charge or should the statutory formula be the only option? | ||

| Is a 5 per cent uplift interest rate as part of the usage charge appropriate? Or should another rate (e.g. the benchmark interest rate) be used? | ||

| Should there be a ‘reasonableness’ test included in the statutory formula or alternatively, are multiple formulas needed? | ||

| Discussion Question 5 | ||

| Minor technical amendments | Are any changes required to the interposed entity rules, apart from s. 109T? For example, should ss. 109V and 109W be amended? | |

| For the purposes of applying s. 109M, is it necessary to have objective criteria to determine whether a loan is made in the ordinary course of a business of lending money? If so, what should be included in the criteria? | ||

| Do similar changes need to be made to other paragraphs of the definition of ‘fringe benefit’ in s. 136(1) of the FBTAA 1986 to clarify the interaction of FBT and Div 7A? | ||

| Discussion Question 6 | ||

| Other issues | Would the insertion of an objects clause in the legislation, consistent with the ‘Policy intent’ outlined on page 2 of this paper, be useful in clarifying the intent of the provisions? | |

| Are there any other issues relevant to the amendments canvassed in this paper that have not been considered? | ||

Implications

Implications