The Treasurer, Scott Morrison, delivered his third Federal Budget on 8 May 2018. The detailed tax measures contained in the 2018–19 Federal Budget are set out in our comprehensive Budget Summary which is available here. The detail of each of the Budget measures — which has been widely reported on — will not be replicated in this article but, a week on from the release of the Budget, it is fitting to make some observations about some of the more interesting and relevant measures.

It is important to note that each of the Budget measures is yet to be introduced into Parliament in the form of an amending Bill, and the often tempestuous legislative passage of tax measures through Parliament assures us that, at least in some cases, the final form of the amendments is likely to differ in substance or timing from the original announcements.

Observations about the state of the Budget

The Government’s 2018–19 Federal Budget reported:

- an estimated deficit for 2017–18 of $18.2 billion — an improvement of $5.4 billion in the underlying cash position for 2017–18 since the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) in December 2017, and $11.2 billion since the release of the 2017–18 Federal Budget on 9 May 2017; and

- a forecast deficit for 2018–19 of $14.5 billion,

with a forecast return to surplus by 2019–20.

[fusion_table]

| Income year | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget (prior to year) |

($37.1b) | ($29.4b) | ($14.5b) | $2.2b | $11.0b | $16.6b |

| MYEFO | ($36.5b) | ($23.6b) | ||||

| Next Budget (during year) | ($37.6b) | ($18.2b) | ||||

| Final outcome | ($33.2b) | ? | ||||

| Gross debt | $565b | $531b | $561b | $578b | $566b | $578b |

| Interest | $16.2b | $13.1b | $14.5b | $12.2b | $12.4b | $12.2b |

[/fusion_table]

Government gross debt is projected to peak at $596 billion at the end of 2025–26 and fall to $532 billion by the end of 2028–29.[1] The amount of net debt inherited by the Liberal Government when it took office in March 1996 was $96 billion, and it took the Treasurer, Peter Costello, 10 years — in eight of which he delivered a Budget surplus — to repay the debt in full by 21 April 2006. This included applying the proceeds from the sale of assets totaling $46.1 billion.

Boldly assuming the same rate of repayment and annual Budget surpluses, we would not expect the Government debt to be retired for many decades. This prompted Peter Costello’s recent warning that most Australians will be dead before the national debt is paid off.

Analysis of selected Budget measures

Personal tax cuts

The Government has announced that it will deliver personal tax cuts by:

- increasing the threshold ceiling of the 32.5 per cent tax rate from $87,000 to $90,000 — from 1 July 2018;

- introducing a new Low and Middle Income Tax Offset of $200 (for income up to $37,000), increasing to $530 (for income up to $90,000), and phasing out once the individual’s income exceeds $125,333 — from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2022;

- increasing the threshold floor of the 32.5 per cent tax rate from $37,000 to $41,000 — from 1 July 2022;

- increasing the threshold ceiling of the 32.5 per cent tax rate from $90,000 to $120,000 — from 1 July 2018; and

- increasing the threshold ceiling of the 32.5 per cent tax rate from $120,000 to $200,000, thereby reducing the number of tax brackets from four to three — from 1 July 2024.

The tax cut delivered by 2. above is well targeted in that it is delivered only to low-to middle-income earners and doesn’t necessitate any compensating adjustments to other rates and thresholds to ensure the benefit isn’t also enjoyed by middle- to high-income earners.

The mode of delivery — i.e. by way of a tax offset — ensures that the Government doesn’t have to fund the tax cut until eligible individuals start lodging their 2018–19 income tax returns … not until at least July 2019.

The Opposition Leader, Bill Shorten, said in his Budget Reply speech on 10 May 2018 that Labor will support the Government’s tax cuts starting 1 July 2018, but we can expect that the Government will face opposition in navigating the remainder of their proposed tax cuts through the Parliament.

Improving the taxation of testamentary trusts

The Government will limit, from 1 July 2019, concessional tax rates (i.e. ordinary adult marginal tax rates rather than the penal rates imposed by Div 6AA of Part III of the ITAA 1936) available to minors receiving income from testamentary trusts to:

- income derived from assets that are transferred from the deceased estate; or

- the proceeds of the disposal or investment of those assets.

We await the detail of the legislative amendments to clarify whether the concessional tax rates will apply to any income distributed to a minor that was derived from assets that form part of the capital trust fund of the testamentary trust; or whether the limit will apply more strictly and be confined to income derived from assets that actually devolved from the deceased estate.

For example, if cash from the deceased estate was settled on the testamentary trust and used to acquire shares following the date of death, would the dividends derived from those shares be ineligible for the concessional tax treatment as the shares did not directly devolve from the deceased estate? Or would it be sufficient that the shares were acquired by the testamentary trust after death using capital funds that did devolve from the deceased estate?

Funding for the ATO to ensure individuals meet their tax obligation

Included in the Budget is $130.8 million of additional funding which will be available to the ATO to increase compliance activities targeting individual taxpayers and their tax agents.

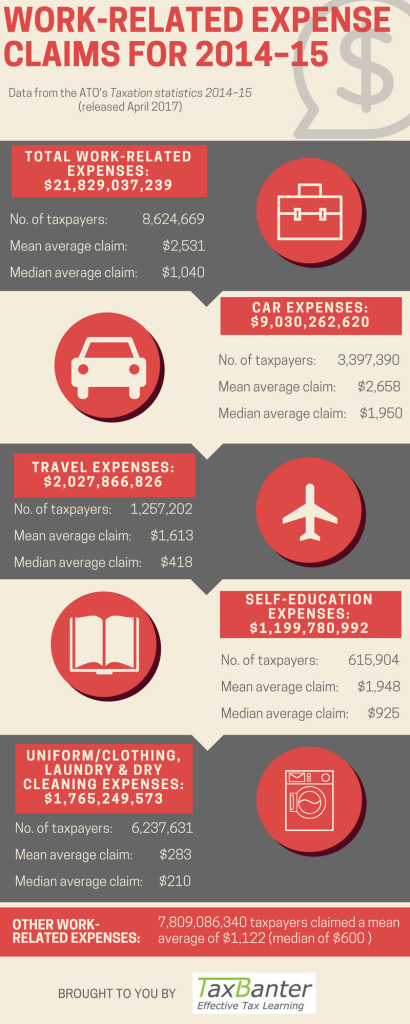

The Budget papers do not mention work-related expenses, but there can be little doubt that this funding is designed to address the Commissioner’s concerns regarding increased non-compliance by individual taxpayers and their tax agents by over-claiming deductions for work-related expenses. His public comments in an address to the National Press Club on 5 July 2017, and at The Tax Institute’s 33rd National Convention in Cairns on 15 March 2018, have revealed that the work-related expenses gap is estimated to be greater than the large corporate tax gap of $2.5 billion. The ATO’s random audits have also revealed that the incorrect claiming of work-related expenses is actually worse in tax returns prepared by tax agents than when self-prepared. Individual taxpayers are now claiming more than $21 billion a year in work-related expenses.

The standard deduction debate

Over the decades, it has often been suggested that the government should introduce a standard deduction. The Henry Review Final Report of December 2009 (recommendation 11 on page 83) recommended that:

A standard deduction should be introduced to cover work-related expenses and the cost of managing tax affairs to simplify personal tax for most taxpayers. Taxpayers should be able to choose either to take a standard deduction or to claim actual expenses where they are above the claims threshold, with full substantiation.

Critics of a standard deduction argue that it would cost the Budget more, because it would allow all taxpayers to claim a standard amount, while those with higher claims would retain their ability to deduct those amounts.

In the 2010–11 Federal Budget, the Government proposed to introduce a standard deduction for work-related expenses and the cost of managing tax affairs of $500 from 1 July 2012, increasing to $1,000 from 1 July 2013. However, the measure did not proceed.

Over the years, while there have been no changes to the legislative requirements when claiming work-related expenses, there has been a growing perception that the various substantiation exceptions — i.e. the $300 for general work-related expenses, the $150 for dry-cleaning and laundry, and $3,300 for car expenses based on the maximum of 5,000 taxable kilometres (contained in Div 28 and Subdiv 900-B of the ITAA 1997) — constitute a standard deduction, without the need to have regard to the legislative requirements in s. 8-1 of the ITAA 1997; namely that the individual must still have actually incurred the amount and it must have been incurred in gaining or producing the individual’s assessable income (the nexus test).

Despite expectations by some commentators that a legislative change in the Budget was likely, the Budget contained no such announcement. So we turn instead to ATO enforcement … the ATO will undoubtedly make productive use of the $130.8 million of additional funding to increase their compliance activities in relation to work-related expenses.

Introduction of an economy-wide cash payment limit

The proposal to impose an economy-wide cash payment limit of $10,000 on all payments made to businesses for goods and services from 1 July 2019 is intriguing. It stems from recommendation 3.1 of the Black Economy Taskforce Final Report which recommended to the Government that payments above the $10,000 threshold will have to be made through the banking system, either electronically or by cheque.

It will be interesting to see how the Government frames this measure — will the cash payment limit be in the form of:

- a criminal offence?

- an extension of monitoring activities by AUSTRAC, the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre which tracks movement of cash in and out of Australia of more than $10,000?

- a reporting obligation imposed on anyone who makes a payment to a business of more than $10,000? or

- more likely, a reporting obligation imposed on any business which receives a payment of more than $10,000?

Regardless of the form of the final measure, it is clearly designed to crack down on cash transactions that fall outside the tax and regulatory system.

Further extending the taxable payments reporting system

Since 1 July 2012, businesses that provide building and construction services and engage contractors have been required to report all payments they make to contractors in a Taxable payments annual report which is due by 28 August each year. This allows the ATO to use the reported information in its data matching programs to identify contractors who have either not lodged tax returns, or not included all their income in returns they have lodged.

From 1 July 2018, the system will be extended to couriers and the cleaning industry. The Government now proposes to extend it further from 1 July 2019 to include:

- security providers and investigation services;

- road freight transport; and

- computer system design and related services.

It is inevitable that, in the future, more industries regarded by the ATO as having a high risk of non-compliance rate will be added to the list.

Further extending the small business immediate deductibility asset threshold

The proposed extension of the small business entity (SBE) $20,000 asset write-off threshold by 12 months to 30 June 2019 will be welcomed by many small businesses. It was originally introduced as a temporary measure for the period 12 May 2015 to 30 June 2017.

It was then extended by 12 months to 30 June 2018. This was in response to the late enactment of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Enterprise Tax Plan) Bill 2017 on 19 May 2017 which increased the SBE turnover threshold from $2 million to $10 million with effect from 1 July 2016. Without the extension to 30 June 2018, affected businesses otherwise had only six weeks left in the 2016–17 income year to take advantage of the opportunity to acquire and write-off assets costing less than $20,000.

The Government is now proposing to extend the $20,000 asset write-off threshold for the second time to 30 June 2019. Tax practitioners are now asking the logical question: Why not make this write-off a permanent feature of the tax system, rather than continually extending it each year, which creates uncertainty until the measure is finally enacted and creates speculation that it will be extended yet again?

Aside from there being an obvious long-term impact on the Budget that would need to be costed (mindful that this is a timing difference only and in the long-term, it makes no difference to the actual deductions claimed by the business over the life of the asset), making it permanent wouldn’t allow the Government to proudly announce each year that they are providing small businesses with a new tax benefit.

Targeted amendments to Division 7A

It’s been a long wait since 3 May 2016 when the Government announced as part of the 2016–17 Federal Budget that, from 1 July 2018, it would amend Div 7A in Part III of the ITAA 1936 in response to recommendations made by the Board of Taxation in its final report of its post-implementation review of Div 7A. The report was provided to the Government on 12 November 2014, and the Government released it on 4 June 2015.

In its announcement as part of the 2016–17 Federal Budget that it would amend Div 7A, the Government provided no detail on what amendments would specifically be made, and whether they would adopt all or part of the 15 recommendations made by the Board of Taxation in its 2014 final report. It was expected that exposure draft legislation of the proposed amendments would have been released ahead of the commencement of the measures on 1 July 2018, and as we crept closer to 1 July 2018, speculation mounted that a deferral of the proposed measures was possible, and desirable.

The Government has affirmed that speculation by announcing a deferral of the proposed measures until 1 July 2019, along with a confirmation that unpaid present entitlements (UPEs) will be included in the scope of Div 7A also from that date.

So where does that leave us …

The debate that has, at times, engulfed the tax profession as to whether a UPE is a ‘loan’ — including the ATO’s controversial ruling TR 2010/3 and accompanying practice statement PS LA 2010/4, the validity of sub-trust arrangements (and the treatment on their expiry) and the calls for an ATO-funded test case — will be finally laid to rest. The amendments will presumably treat all UPEs as a loan that will need to be managed under the usual Div 7A rules.

We are keenly waiting to see whether the Government will proceed wholly or partly, or not all at, with recommendations 6 and 8 from the Board of Taxation’s final report which, amongst other things made the following recommendations:

… the Board recommends enacting legislation that prescribes [that] … all pre-1997 loans would be deemed to be new complying Division 7A loans, with a 10-year term starting from the application date of the new provisions; …

and:

The Board recommends introducing legislative amendments to align the treatment of UPEs with the treatment of loans for Division 7A purposes …

For nearly three years, there has been speculation that, from 1 July 2018, the Government would legislate to freshen up all loans made by companies prior to 4 December 1997 (which have been quarantined since that date) and UPEs arising prior to 16 December 2009 (which have been similarly quarantined since that date). Now the speculation will continue for another 12 months as we await the detail of the proposed amendments to Div 7A, and hope that the release of exposure draft legislation is imminent.

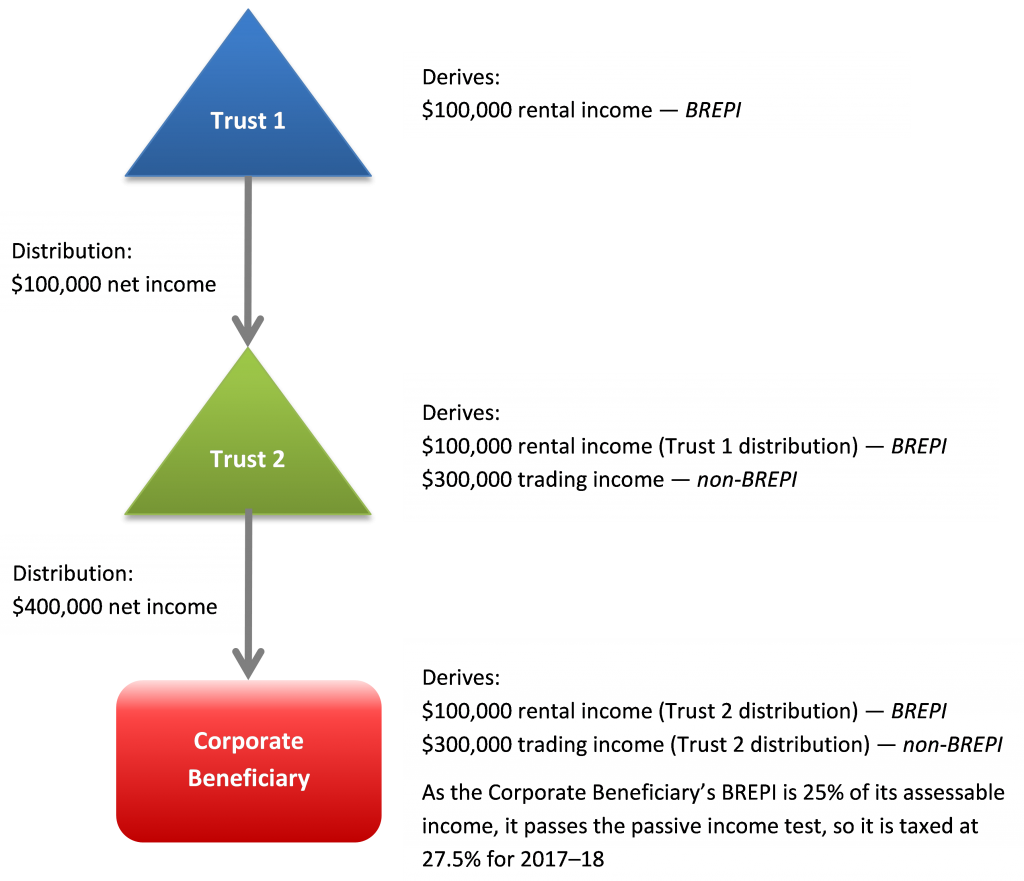

Extending anti-avoidance rules for circular trust distributions

The vague announcement that the Government would, from 1 July 2019, extend to family trusts a specific anti-avoidance rule that applies to other closely held trusts that engage in circular trust distributions has caused confusion as to which rules the Government is referring to.

Not about s. 100A

Section 100A of the ITAA 1936 (about reimbursement agreements which the Commissioner has linked to circular distributions involving discretionary trusts and corporate beneficiaries: see example 5 in this link) has been mentioned as a possible subject of this amendment. However, family trusts (i.e. those which have made a family trust election under Schedule 2F of the ITAA 1936) are already subject to s. 100A. This Budget measure has nothing to do with s. 100A.

It’s about the closely held trust reporting rules

The Budget measure relates to the integrity rules in Div 6D of III of the ITAA 1936 — the closely held trust reporting rules — otherwise known as the ‘trustee beneficiary statement’ or the ‘TB statement’ at labels P and Q of the statement of distribution in the trust tax return. These rules required the trustee of a closely held trust to make a correct TB statement if:

- a share of the trust’s net income is included in the assessable income of a trustee beneficiary (under s. 97 of the ITAA 1936) and the share includes an untaxed part; or

- a trustee beneficiary is presently entitled at the end of the income year to a share of a tax-preferred amount of the trust.

If a trustee fails to make a correct TB statement in respect of a beneficiary when required, the trustee is liable to pay trustee beneficiary non-disclosure tax on the untaxed part of the beneficiary’s share of net income at the rate of 47 per cent.

A trustee is not required to make a correct TB statement if the trust is an excluded trust. Currently, a trust that has a valid family trust election or interposed entity election in force is an excluded trust. This means that family trusts that distribute to other trusts are not required to make a correct TB statement.

In our opinion, the Budget measure proposes to amend paragraph (c) — and likely paragraphs (d) and (e) as well — of the meaning of ‘excluded trust’ in s. 102UC(4) of the ITAA 1936, with the result that family trusts that distribute to other trusts would also have to make a correct TB statement.

Audit of SMSFs

The Government’s proposal to allow well-behaved SMSFs to be audited only every three years is a perplexing one. Currently, all SMSFs are required to be audited annually to identify whether they have complied with all their obligations under the SIS Act.

The SMSF would be permitted to be subject to a three-yearly audit cycle if it has a history of three consecutive years of clear audit reports and the fund’s annual return is lodged in a timely manner.

Allowing eligible SMSFs to be audited only every three years raises the following issues:

- It is currently an annual requirement, everyone accepts that, so why change it?

- Would relaxing the need to have an audit each year result in increased non-compliance by trustees with the SIS Act?

- Will this result in the professional fees of auditors of SMSFs being reduced by two-thirds?

- How will auditors of SMSFs resource their work flow — will it be eerily quiet for two years only to have an insurmountable volume of work in year three? Or would they be able to stagger the audits over the three-year period across their client base? And which eligible client starts their three-year cycle first?

- Will this save trustees of SMSFs any cost? At first glance, they would incur an audit fee only every three years, but would the amount of that fee increase due to the auditor having to scrutinise three years’ worth of transactions and activity instead of just one?

- Will greater responsibility fall on tax agents and accountants in the intervening periods between audits? We are not suggesting that tax agents and accountants would assume the audit responsibility, but the absence of an auditor for the relevant years may result in an increased role played by the tax agent or accountant in the administration of the SMSF.

Tax agent fees

In an innocuous announcement that the Tax Practitioners Board will be provided with $20.1 million of funding over four years from the 2018–19 income year to assist it in meeting its responsibilities, the detail of the Budget papers reveals that this measure will be funded by increasing tax agent registration fees from 1 July 2018.

The Tax Practitioners Board has already announced the proposed new fees which will increase by 35 per cent. These are set out in the table below.

[fusion_table]

| Registration application fees# | Current fees where carrying on business | Current fees where not carrying on business | Proposed new fees* from 1 July 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax agent | $500 | $250 | $675 |

| Tax (financial) adviser | $400 | $200 | $540 |

| BAS agent | $100 | $50 | $135 |

[/fusion_table]

# The application category ‘does not carry on a business’ will no longer exist.

* The proposed application fee increases are expected to be effective from 1 July 2018, with the application fee amounts being subject to an annual consumer price index adjustment from 2019–20 onwards.

Final thoughts …

The analysis and circumspection regarding the 2018–19 Federal Budget measures has only just begun and will be amplified once the measures are introduced into Parliament in the form of legislative amendments. It would be prudent to bear in mind that this is likely to be the Government’s last Budget before the next federal election. Accordingly, there is a strong likelihood that some of the Budget measures that proceed beyond a mere announcement into the form of a bill will not be enacted before the election is called, resulting in the lapsing of the of the bill; the fate of the measure would then be determined after the next election.

![]() Note

Note

Practically the last possible date for a half-Senate election to take place before the three-year terms expire is 18 May 2019. Whether held simultaneously with an election for the Senate or separately, an election for the House of Representatives must be held on or before 2 November 2019. It is likely that the Government will hold an election for the Lower House at the same time as the half-Senate election takes place, i.e. by 18 May 2019.

We keenly await the release of more detail on these, and the other, Budget measures and will advise of any developments in a future post.

1. Australian Government. Budget 2018–19, May 2018, Budget Paper No. 1, Statement 7, pages 7-3 and 7-8, Table 3.

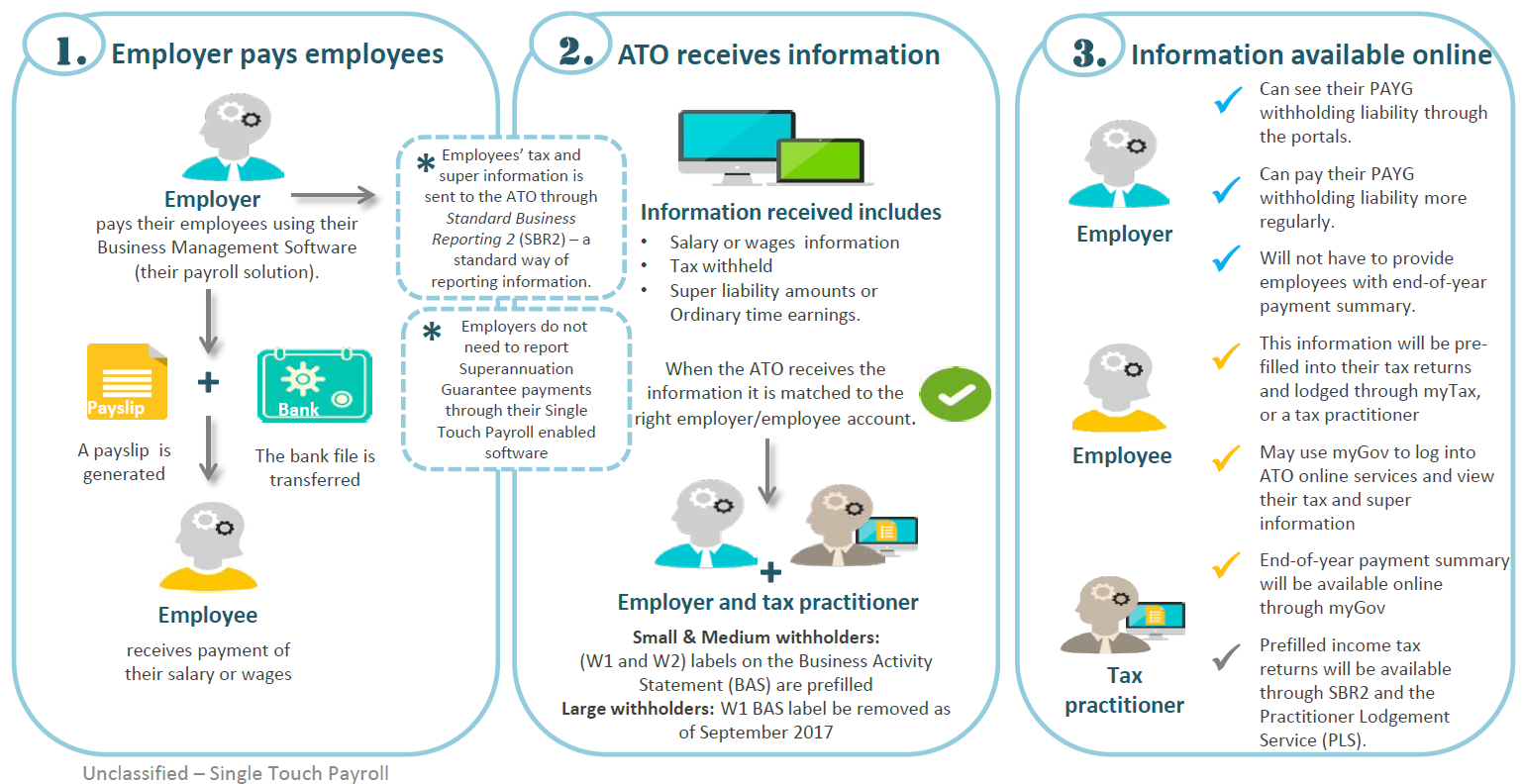

![Single Touch Payroll [Infographic]](https://taxbanter.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Small-businesses-payroll-software.png)

Tip — ABSIA product catalogue

Tip — ABSIA product catalogue

Implications

Implications Critical Point

Critical Point

![ATO focus on work-related claims [Infographic]](https://taxbanter.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Work-Related-Expense-Claims.png)