[print-me]

The ATO has an eye on every 2017 work-related expense claim

As soon as Tax Time 2017 began, the ATO activated its version of a warning system via the Australian media to caution individual taxpayers and their advisers against over-claiming work-related expenses.

While the ATO will certainly be looking at unusually high claims for work-related expenses (WRE) of all types, car expenses and clothing and laundry expenses are the two categories which will receive the most scrutiny for 2016–17.

Another year … another ATO crackdown on WRE deductions

Following ATO audits and reviews of 2015 individual tax returns, which resulted in revenue adjustments of over $1.1 billion in income tax, the ATO has flagged its concerns about inappropriate deductions.

In a bid to reduce the magnitude of incorrect claims, in June 2017 — just prior to year end — Assistant Commissioner Kath Anderson issued a media release aimed at educating taxpayers on WRE deductions before they lodge their 2017 returns.

This Tax Time, tax practitioners must be alert for clients who may misunderstand their entitlement to WRE deductions to prevent ATO attention on dubious claims.

While the ATO will look at all risk areas in lodged 2017 tax returns, it will pay special attention to deductions in two categories: car expenses and clothing and laundry expenses.

The ATO’s ‘golden rules’ of WRE deductibility

The media release contains the ATO’s oft-repeated ‘three golden rules’ for deductibility of a WRE under the general deduction rules. These rules are paraphrased and expanded below.

| Golden rule | Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Generally, an individual employee has incurred a particular WRE expense if they have actually paid for it — and it was not reimbursed by their employer.

(Note that expenditure may be deductible if the taxpayer received an allowance rather than a reimbursement from the employer. See TR 92/15 on the difference between an allowance and a reimbursement.) |

|

The expenditure must be directly related to earning employment income. Further, the amount cannot be:

|

|

Generally, records to support all deductions must be kept for five years from lodgment, although specific substantiation rules apply to certain categories of WREs and there is an exception for total claims that do not exceed $300. |

Airing the dirty laundry about clothing-related claims

Why is the ATO concerned about clothing-related claims?

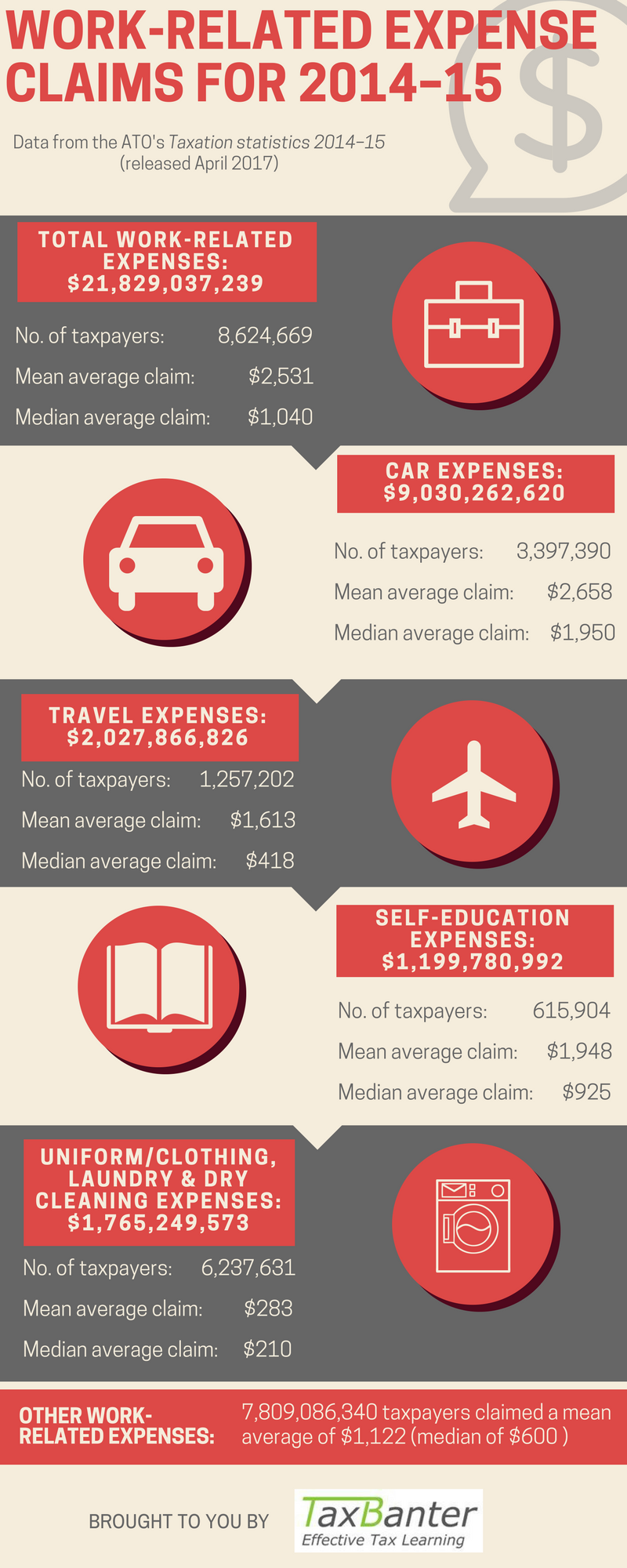

In 2015–16, over 6.3 million taxpayers claimed almost $1.8 billion in clothing and laundry WRE. Interpreting these statistics at an individual taxpayer level, this means that almost half of Australia’s 13 million individuals who lodged 2016 returns had spent money on eligible items, and that each individual claimed a mean average of $285. Claims in this category have also increased by around 20 per cent over the past five years. These figures have caused the ATO concern that deductions are being erroneously claimed.

Consequently, Ms Anderson issued another media release in July 2017 warning taxpayers about incorrectly claiming clothing and laundry expenses.

Three tips for correctly claiming clothing and laundry expenses

Employer dress code does not mean costs of clothing are deductible

TR 97/12 states that expenditure on ‘conventional’ clothing is unlikely to be deductible — even if the taxpayer’s employer requires or expects the taxpayer to wear a particular type of conventional clothing, or where that clothing is perceived as being important to success in the profession. A business suit, or black attire required to be worn by staff working at a restaurant or a department store, are common examples.

Fundamentally, expenditure on clothing and footwear is properly characterised as a personal or living expense. However, the expenditure will be considered work-related — and therefore deductible — if there is a sufficient nexus to the taxpayer’s income-earning activities.

In the ATO’s view, for the requisite nexus to exist, the clothing must distinctively identify the wearer as a person associated with a particular profession, trade, vocation, occupation or calling — i.e. occupation specific clothing. ATO examples include a barrister’s robes, a nurse’s traditional uniform, a cleric’s ceremonial robes and a chef’s chequered pants.

The ruling emphasises that clothing which could be worn in a number of occupations is not occupation specific clothing. A business suit (the same one of which could be worn by, for example, an accountant, a real estate agent and a retail store manager) would fall into this category, even if the taxpayer has no choice about wearing one to work under their workplace dress code.

There is no ‘standard deduction’ of $150 for laundry expenses

There is a statutory substantiation exception for deductions for washing, drying and ironing (laundry) expenses if the amount of the laundry expense claim does not exceed $150.

However, this does not provide taxpayers with a ‘standard deduction’ of $150. The taxpayer must still be able to verify that they actually incurred the expenditure — i.e. that a certain number of loads of eligible clothing were washed, dried and/or ironed.

To make the record-keeping easier, the ATO provides standard rates which can be used for a total laundry claim that does not exceed $150:

- $1 per load — if the load only comprises work-related clothing; and

- $0.50 per load — if the load includes private clothing as well as work-related clothing.

It is not compulsory to use these rates but the taxpayer will need to be able to explain any other basis of calculation. TR 98/5 provides practical guidance on calculating laundry deductions.

Note:

- A deduction for laundry expenses — and the substantiation exception — is only available where the clothing or footwear is used for income-producing purposes and the expense is occasioned by the performance of those duties.

- Laundry expenses that are eligible for the substantiation exception do not include dry cleaning expenses (which may nevertheless be claimed as a WRE subject to the usual substantiation rules).

Not all ‘protective’ items are deductible ‘protective clothing’

Expenditure on work-related ‘protective clothing’ is deductible. Whether an item is ‘protective’ is determined by reference to tax law and ATO criteria; it is not tested by reference to common social norms.

Under the tax law, protective clothing must protect the taxpayer or someone else from risk of death, disease, injury, damage to clothing, or damage to an artificial limb or medical aid. Specific examples include goggles, hard hats and safety boots worn on a work site. Less clear-cut are items used in everyday life such as sunglasses, closed-toe shoes or boots, waterproof clothing and sunscreen.

The ATO’s criteria for determining whether items worn at work are work-related protective clothing are set out in TR 2003/16 and include whether:

- the work environment could be harmful if adequate safety precautions are not taken (e.g. extreme weather conditions);

- the use of the item in the work place makes it unsuitable for private use (e.g. the protective clothing becomes too soiled for private use);

- the expenditure is in addition to the taxpayer’s normal private expenditure on such items (e.g. the taxpayer acquires additional protective clothing to guard against unsafe conditions);

- the item is qualitatively different to comparable items used privately (e.g. the item can cope with more rigorous work conditions);

- the item is used principally for income-producing activities (i.e. private use is no more than incidental);

- the taxpayer is required to use the item by the employer, safety laws or an industrial agreement (e.g. an industrial award provides for an allowance to purchase the item);

- the use of the item adds to workplace productivity (e.g. the wearer can work for longer periods); and

- any other feature indicates a work-related character.

Australians are taught from childhood to ‘slip, slop, slap’ to protect themselves from sun damage. Based on the examples in TR 2003/16, expenditure on sunglasses, sunscreen and sun hats are likely to be deductible to an outdoor worker in a horticulture business, but not to an office worker taking a short walk from the office or car park to a client.

Over-claiming car expenses — from ‘go’ to ‘no’

Why is the ATO concerned about car expense claims?

Ms Anderson issued another WRE media release in August 2017, this time focusing on car expenses.

In 2015–16, over 3 million taxpayers claimed a total of approximately $8.5 billion in car expenses. This equates to a mean average of $2,833 per claimant.

The ATO is particularly concerned by a pattern in their 2016 tax return data: a ‘significant proportion’ of those 3 million claims were ‘right at the limit that does not required detailed records’. Under the law, deductions using the cents per kilometre method do not require written evidence if no more than 5,000 kilometres are claimed.

In a simplistic exercise, dividing the $2,833 mean average deduction by the cents per kilometre rate of $0.66 — and disregarding the logbook method — equates to 4,292 kilometres per average claim.

Three tips for correctly claiming car expenses

There is no ‘standard deduction’ for 5,000 kilometres

There is a legislated substantiation exception for claims made under the cents per kilometre method — capped at 5,000 kilometres. However, this does not represent a ‘standard deduction’. The taxpayer is entitled to a deduction only for kilometres actually travelled in the course of producing assessable income and which is not private in nature.

The substantiation exception means that there is no requirement to keep detailed records in a logbook or similar. However, the taxpayer must still be able to verify that they undertook the purported trips for a work purpose, and that the kilometres claimed reflect the distances actually travelled by car during those trips.

Deductions may be available for using someone else’s car

The tax law clearly states that a taxpayer is entitled to a car expense deduction in relation to a car only if the taxpayer making the claim owned or leased the car.

Therefore, a taxpayer is generally not eligible for deductions relating to a work trip taken in a car borrowed from a colleague, relative or friend.

However, the ATO will in practice allow a taxpayer to claim car expenses in relation to a car registered in the name of another individual if the taxpayer contributes financially to the purchase or lease costs. This is most common in family arrangements where a car is registered in the name of one individual, but their spouse/partner also drives it and paid for some or all of the acquisition cost.

A private ruling confirms that the ATO will consider a taxpayer to ‘own or lease’ a car for the purposes of car expense deductions if they can demonstrate their financial contribution to any of the following:

- the initial purchase of the car;

- lease payments;

- hire purchase agreements; or

- loan payments relating to the car.

Note: merely contributing to ongoing running costs of the car is insufficient to prove ownership.

No deductions for a salary packaged car

An employee is prevented from claiming car expenses in relation to a car provided by the employer under a salary packaged novated lease arrangement — for two reasons. It does not matter whether those expenses otherwise meet the general deductibility criteria. It also does not matter whether the employee pays the costs from pre-tax or post-tax income.

Firstly, the tax law specifically provides that car expenses are non-deductible to an employee where:

- the car is provided for the employee’s exclusive use; and

- any time during the income year, the employee or a relative is entitled to use the car for private purposes (note: entitlement to private use is sufficient — actual private use is not necessary).

The law ensures that any contribution by the employee is used solely to reduce the employer’s FBT liability and that the employee cannot double dip by also claiming a personal deduction for the expenditure.

Secondly, the ATO considers that an employee does not ‘own or lease’ a car under a novated lease arrangement. The car expense deductibility rules require the taxpayer to own or lease the car.

ATO guidance and compliance activities

Specific ATO guidance on WREs

In the 1990s, the ATO issued a suite of taxation rulings for employees working in specific industries and occupations, including real estate industry workers; building workers; itinerant workers; truck drivers; nurses; teachers; and lawyers.

For a general summary of the guidance in all rulings for specific industries and occupations, see this ATO webpage.

The following guidance is also available:

- TR 98/9 — relating to self-education expenses;

- PS LA 2005/7 — which sets out the ATO approach to substantiation of WREs; and

- TR 93/30 — which differentiates between a home office and ‘working from home’.

Further, the ATO is currently updating its technical guidance on employee travel expenses: TR 2017/D6.

The impact of technology on WRE deductions

Recent years have seen marked advancements in ATO technology. Three key developments may impact how practitioners and their clients approach WRE claims in 2017 tax returns:

Tax return preparation — ATO app: myDeductions tool

The myDeductions tool in the ATO app can help individual taxpayers to keep accurate records, including photos of receipts, during the income year. For example, a taxpayer can enter the details of expenses incurred during a work-related trip in real-time while they are travelling, without the need to keep track of paper receipts for months before tax return preparation. A tax agent can request a client to send them the data directly from the app. The practitioner can then review the data and the photo evidence, and adjust the amounts if necessary before lodging.

Before lodgment — Real-time checks of WRE deductions

The ATO first introduced real-time checks of deductions for 2016 tax returns. If the taxpayer’s WRE claims were ‘substantially higher’ than others in similar occupations with similar incomes, a message appeared asking for the claims to be checked prior to lodgment.

The ATO has taken this a step further for 2017 tax returns. A new message in the Tax Agent Portal

pre-filling report displays if the taxpayer’s 2015–16 WRE deductions were high in comparison to other taxpayers in similar occupations with similar incomes. The ATO intends to deliver this information through the practitioner lodgment service (PLS) in future years.

A warning message is an indicator that the taxpayer may be brought into the ATO’s compliance activity net by virtue of the size of their WRE deduction. It should also serve as a pre-lodgment reminder to check that the taxpayer can verify all their WRE deductions.

After lodgment — Detection of non-compliance

In recent years, the ATO has used increasingly sophisticated tools and data analytics to scrutinise every tax return that has been lodged. It is increasingly easy for the ATO to automatically select higher-than-average deductions for review. Tax agents and their clients need to be able to produce conclusive evidence that the amount has been incurred.

Final observation …

Perhaps the taxpayer has misunderstood the operation of the substantiation exception … perhaps the taxpayer was able to ‘get away’ with exaggerated claims for WRE deductions in the past … perhaps the ATO’s compliance activities and data analytics many years ago were not as sophisticated as they are now …

But the mindset — that ‘Everyone cheats a bit, so I can too’; ‘My mates claim it’; ‘I’ll just claim a little bit extra and no one will notice’; ‘There’s a standard deduction, so I can automatically claim $150 of laundry, or $300 of WRE, or 5,000 kilometres of car expenses without receipts’ — is one that the ATO will not tolerate. WRE claims are, according to the Commissioner of Taxation who spoke at the National Press Club on 5 July 2017, ‘truly in our sights and we will be lifting our education, our support, our attention, our scrutiny and enforcement in this area’.

If every single person paid the correct amount of tax they are supposed to under the law and no one claimed anything they are not entitled to, revenue collections would unquestionably be higher and the rate of tax payable could be lower for everyone.

Click to see infographic: Category breakdown of work-related expense claims 2014–15:

Contact Taxbanter to discuss your 2018 tax training needs: 03 9660 3500 | enquiries@taxbanter.com.au

![Australian House Prices [Infographic]](https://taxbanter.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Median-Houseprice-Infographic-Cover.png)

Critical Point

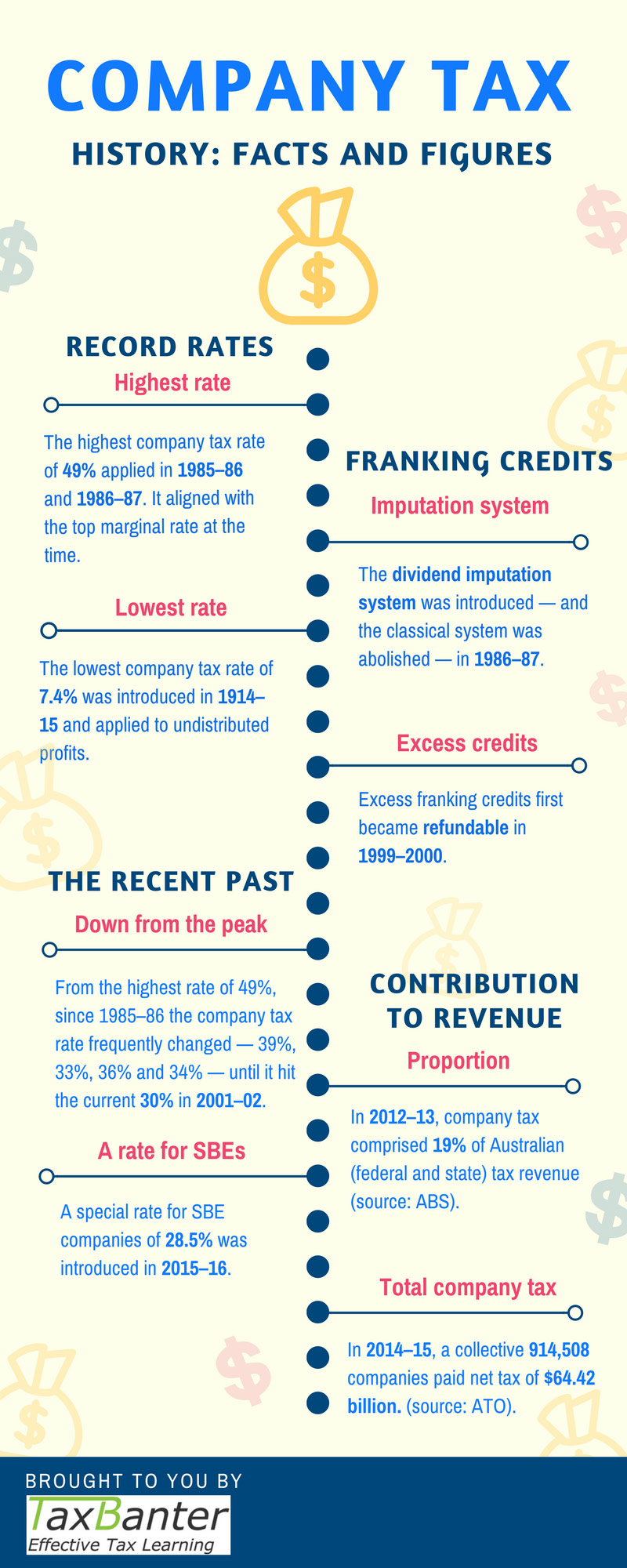

Critical Point![Company Tax Cuts [Infographic]](https://taxbanter.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Company-Tax-Cuts-infographic-Cover.png)

Definition

Definition