The Tax Practitioners Board (TPB) has released long-awaited draft guidance on the new breach reporting obligations due to commence 1 July 2024 setting out its preliminary views on key aspects of the rules and its proposed compliance approach.

The Treasury Laws Amendment (2023 Measures No. 1) Act 2023 introduced significant changes to the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (TASA) in relation to the regulation of tax agents.

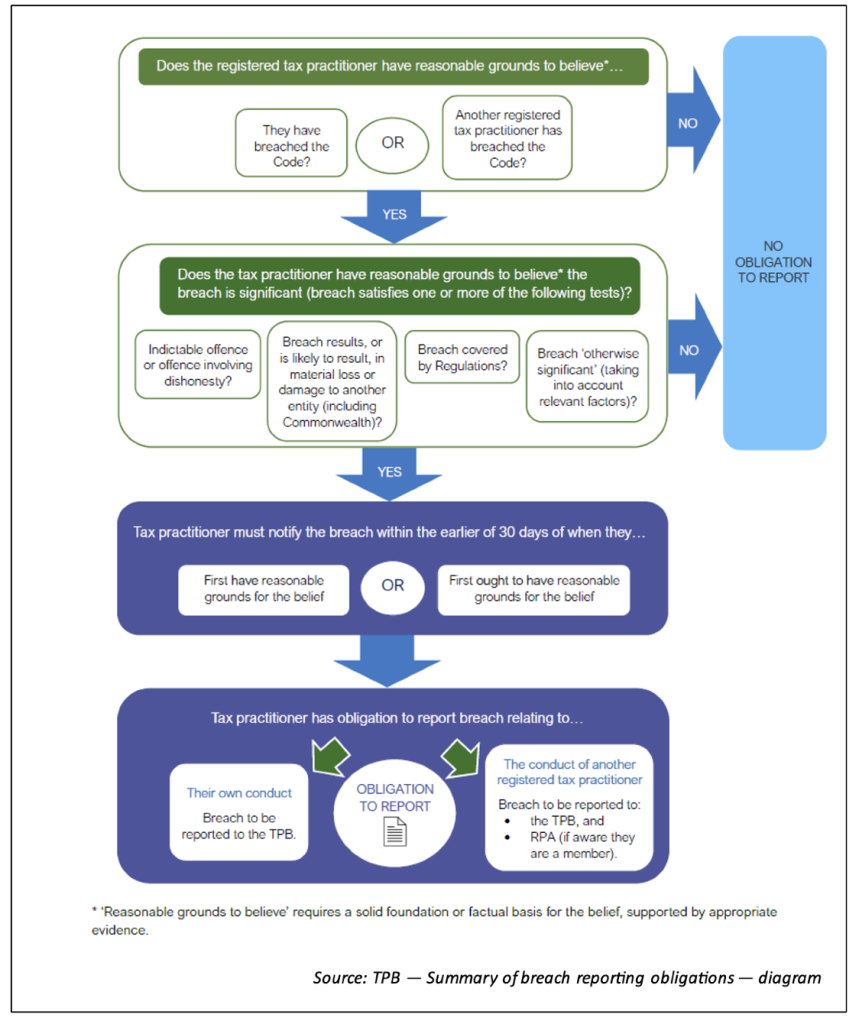

Amongst other things, the Act imposes new mandatory notification requirements — from 1 July 2024 — for a registered agent who has committed a significant breach of the Code of Professional Conduct (the Code) or who becomes aware of a significant breach of the Code committed by another registered agent.

A registered agent will be required to:

The TPB’s package of draft guidance materials comprise an exposure draft information sheet (the draft Information Sheet), a summary document and a high-level decision tree. These documents explain the TPB’s preliminary views in relation to:

This article summarises the TPB’s preliminary views in relation to the application of the law. Refer to this previous Banter Blog article for a general overview of the breach reporting legislation and to the package of TPB draft materials for detailed commentary supporting its views.

While the legislation refers to registered tax (and BAS) agents, the draft guidance generally refers to registered tax (and BAS) practitioners. In this article the terms agents and practitioners are used interchangeably and refer to both registered tax and BAS agents.

Legislative references are to the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (TASA) and the Tax Agent Services Regulations 2022 (TASR).

Comments and Submissions

![]() Address: Tax Practitioners Board, GPO Box 1620, Sydney NSW 2001

Address: Tax Practitioners Board, GPO Box 1620, Sydney NSW 2001

![]() Email: tpbsubmissions@tpb.gov.au

Email: tpbsubmissions@tpb.gov.au

![]() Due date: 28 May 2024

Due date: 28 May 2024

Given the amount of material in this article and in the TPB’s draft guidance package, here is a short summary of the key points to note.

The law defines a significant breach of the Code as a breach which:

![]() Important

Important

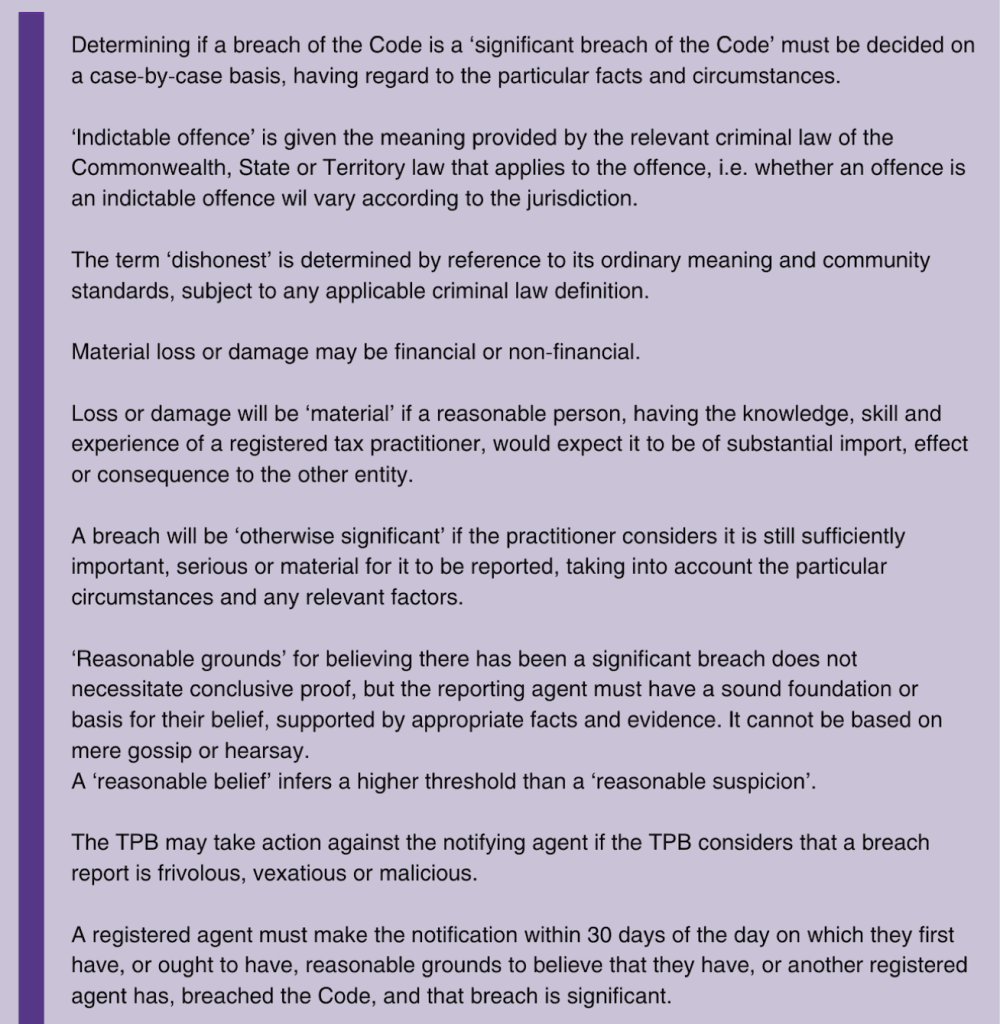

Determining if a breach of the Code is a ‘significant breach of the Code’ must be decided on a case-by-case basis, having regard to the particular facts and circumstances.

The TPB states that the breach reporting obligations do not make a distinction between ‘actual’ or ‘alleged’ breaches. However, registered tax practitioners must have reasonable grounds to believe there has been a significant breach. They do not need to have conclusive proof, but they must have a solid foundation or basis for their belief, supported by appropriate facts and evidence.

If a breach is covered by more than one arm of the definition, a tax practitioner only needs to report the breach to the TPB and the relevant professional body (where relevant) once.

Offences may include, but are not limited to, those involving fraud (including social security and tax fraud), theft/stealing, money laundering, bribery and corruption, embezzlement, dealing with proceeds of crime, dishonest use of position, knowingly making false or misleading statements, cyber-crimes and unlawfully obtaining or disclosing information.

‘Indictable offence’ is not defined in the TASA or TASR. As such, the term is given the meaning provided by the relevant criminal law of the Commonwealth, State or Territory law that applies to the offence. Whether an offence is an ‘indictable offence’ will therefore vary according to the jurisdiction. Generally speaking, indictable offences are the more serious criminal offences heard in a higher court, such as the District or Supreme Court, and may require a trial by judge and jury.

The TPB considers that the meaning and scope of the term ‘dishonest’ is determined by reference to its ordinary meaning and community standards, subject to any express definition that applies in the criminal law relevant to the offence. The conduct giving rise to the offence must include an element of ‘dishonest’ conduct.

The TPB considers that ‘loss or damage’ captures any detriment, disadvantage, injury, harm or cost to another entity resulting, or likely to result, from the breach, provided it is considered ‘material’. It covers both financial and non-financial ‘loss or damage’.

For example, it may include a financial loss to a client, damage caused to the reputation of a client or the Commonwealth, a loss of privacy, breach of confidential information, or unauthorised disclosure of a client’s identity, and loss or damage in the form of adverse impacts on the health and wellbeing of clients as the result of a tax practitioner’s conduct.

In relation to materiality, a registered tax practitioner may also not be aware of, or in a position to appreciate, the exact nature and scope of the loss or damage, including how and to what extent it has impacted the other entity. The TPB considers that loss or damage will be ‘material’ if a reasonable person, having the knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner, would expect it to be of substantial import, effect or consequence to the other entity.

The TPB considers that a breach will ‘result’ in material loss or damage to another entity, if there is a sufficient connection or relationship between the breach and the loss or damage, such that it can be said that the loss or damage is a consequence, outcome or effect of the breach. For a breach to be ‘likely’ to result in material loss or damage, the loss or damage needs to be a probable consequence, outcome, or effect of the breach, not just a mere possibility. If a reasonable person, having the knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner, would expect the loss or damage to result from the breach in the sense of it being a real and not remote possibility, this will be sufficient.

The TPB considers a breach of the Code to be ‘otherwise significant’ if the practitioner considers it is still sufficiently important, serious or material for it to be reported, taking into account the particular circumstances, notwithstanding the fact it is not covered by indictable offence or material loss or damage provisions. This will be the case if the breach (or potential breach) reflects, or is capable of reflecting, on a tax practitioner’s fitness and proprietary for registration, and their conduct more broadly as a registered tax practitioner in providing tax agent and BAS services to a competent standard.

The number and frequency of similar breaches

The greater the number or frequency of similar breaches, the more likely it may be that the breach is significant. Even if a breach, when considered by itself, is minor in nature, it may still be ‘significant’ when considered against the background of other similar breaches.

The impact of the breach on the tax practitioner’s ability to provide tax agent or BAS services

If a registered tax practitioner considers the breach will or may negatively impact their, or another tax practitioner’s, ability or capacity to provide the tax agent or BAS services covered by their registration, this may indicate that the breach is ‘significant’.

The extent to which the breach indicates that the tax practitioner’s arrangements to ensure compliance with the Code are inadequate

If the nature of the breach itself, or the circumstances surrounding the breach, indicates that there are broader systematic issues with the arrangements that a tax practitioner has in place to ensure compliance with the Code, it is more likely that the breach will be ‘significant’.

![]() Note

Note

Registered practitioners are not limited to the above factors. They can take into account any factor they consider relevant, which may include the:

The conduct of another registered agent

The TPB recognises that establishing whether a breach is ‘significant’ in relation to the conduct of another registered tax practitioner may be more difficult. However, provided there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to conclude that the breach is ‘significant’, and they can substantiate their reasoning, this will be sufficient.

For example, a registered tax practitioner may be operating in a small firm and have knowledge or reasonable grounds to make that conclusion about the professional conduct of their partner. In another circumstance, a registered tax practitioner may be apprised of another tax practitioner’s misconduct by virtue of a review or report, including via an audit, an internal review, or a ‘due diligence’ analysis associated with the purchase or sale of a business.

The TPB encourages registered practitioners to report in ‘finely balance circumstances’ or where they are undecided as to whether a breach is otherwise significant but have reasonable grounds for suspecting it may be.

Currently there are no breaches prescribed in the TASR as being ‘significant breaches’.

A registered tax practitioner must have ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ that they or another registered tax practitioner has breached the Code and that the breach is a significant breach.

In the TPB’s view it is clear that the phrase ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ requires the registered tax practitioner to have a sound foundation or basis in the circumstances on which to credit or form their belief that they, or another tax practitioner, has breached the Code and that breach is ‘significant’.

Further, it is established in case law that when legislation uses the term ‘reasonable grounds’ to describe a basis for a state of mind, for example, in forming a belief about a matter, there needs to be an existence of facts which are sufficient to induce that state of mind in a reasonable person.[ Whether a person has reasonable grounds for a belief is an objective test and it is irrelevant whether the person subjectively believes they have reasonable grounds. A ‘reasonable belief’ is generally considered to infer a higher threshold than a ‘reasonable suspicion’.

The foundation or basis for the belief does not need to be established to a high evidentiary standard. There does not have to be conclusive proof. It is sufficient if a reasonable person, possessing the required knowledge, skill and experience of a registered tax practitioner would, when objectively considered, form the belief on the same grounds in the same circumstances.

Generally, the TPB would expect registered tax practitioners to be aware of the facts and circumstances surrounding a breach of the Code by their own conduct and be well-placed to make an assessment about whether notification to the TPB is warranted.

Whether a registered tax practitioner has ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ that another tax practitioner has breached the Code, and the breach is significant, may be more difficult to establish.

Factors to consider may include:

![]() Warning

Warning

If a registered practitioner has based the belief on hearsay, gossip or the opinion of third parties and has not made further enquiries or obtained independent verification or advice to substantiate the belief, this will not be sufficient for them to have ‘reasonable grounds’ for that belief.

The TPB will assess the information provided and make further enquiries (as appropriate) to ensure the reporting of a significant breach relating to another tax practitioner’s conduct is reasonable and is not frivolous, vexatious or malicious.

The TPB may take action against the notifying tax practitioner if the TPB considers that a breach report is frivolous, vexatious or malicious, for example, if the claim involves the making of a false or misleading statement. Such situations may raise issues about the notifying tax practitioner’s compliance with other requirements of the TASA.

Significant breaches of the Code must be notified to the TPB and applicable professional association (where relevant) within 30 days of the day on which the registered tax practitioner first has, or ought to have, reasonable grounds to believe that they have breached the Code and that breach is significant, or that another registered tax practitioner has breached the Code, and that breach is significant.

The term ‘have’ looks at the point in time when the registered tax practitioner actually forms the view that there are reasonable grounds for believing that a significant breach has occurred. That is, when they first have a sound foundation and basis for the belief.

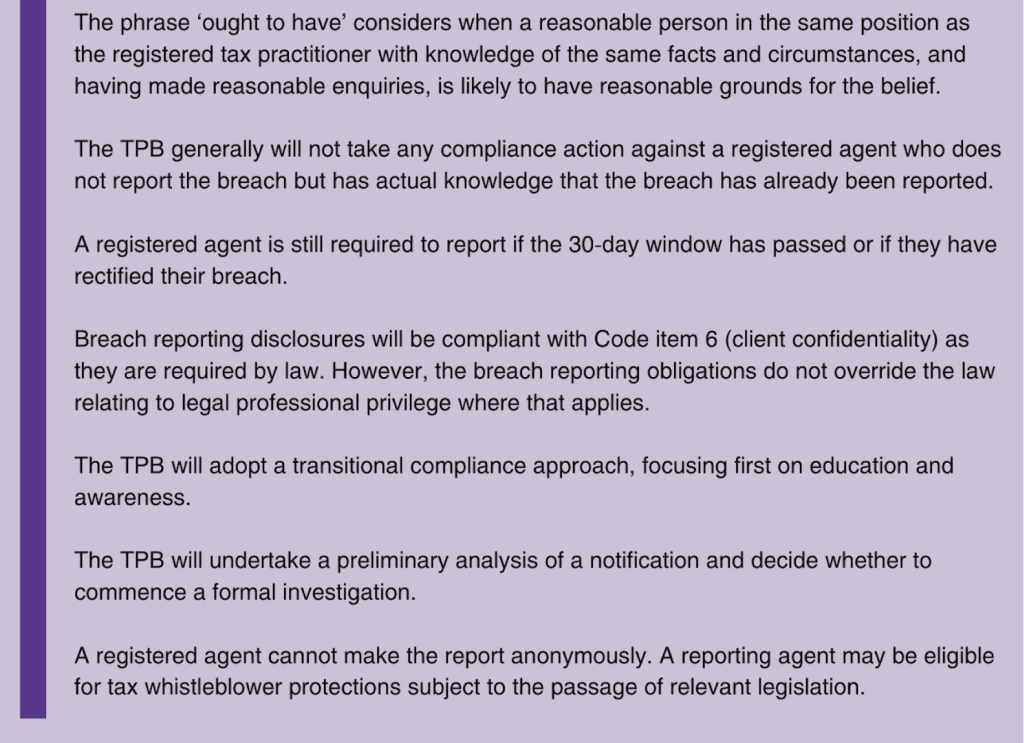

The phrase ‘ought to have’ looks at the point in time when the tax practitioner is objectively taken to have reasonable grounds for believing that a significant breach has occurred. The test is an objective one, which considers when a reasonable person in the same position as the registered tax practitioner with knowledge of the same facts and circumstances, and having made reasonable enquiries, is likely to have reasonable grounds for the belief.

If there are multiple grounds supporting the belief, and these grounds become evident at different times, the 30-day timeframe runs from when the tax practitioner first had sufficient grounds for the belief.

If a reasonable person in the same position as the registered tax practitioner would have had reasonable grounds to believe that a significant breach had occurred at an earlier time than when the tax practitioner actually formed the belief, the notification period runs from that earlier point in time.

If a tax practitioner does not comply with the 30-day notification period, they must still report the breach. The tax practitioner must give reasons for the delay in notifying the breach and support their claim with appropriate evidence and facts. The TPB will take this information into account when assessing the report and determining the appropriate compliance action to take.

If a registered tax practitioner has actual knowledge that a significant breach of the Code has already been reported by another tax practitioner, the TPB will not, as a general rule, take any compliance action if they do not report the breach, where the practitioner:

A practitioner may have actual knowledge that the breach has already been reported because, for example, the breach was reported by a member of the same firm or the TPB has publicly released information about the breach.

A registered tax practitioner still has an obligation to report a significant breach if the breach has been ‘rectified’, or they have taken steps to address or remedy the breach. Rectification of a breach is a factor the TPB may take into consideration when deciding what further action it might take.

Relating to own conduct: use the Notify a change in circumstances form

Relating to the conduct of another registered tax practitioner: use the Online Complaints form

If a registered tax practitioner has reasonable grounds to believe that another practitioner has breached the Code and it is a significant breach, and the other practitioner is a member of a registered professional association recognised by the TPB, they must notify that association of the breach in writing.

Here is a list of recognised professional associations that are accredited by the TPB.

The TPB Register may include information about whether a registered tax practitioner is a member of an association. The TPB does not generally verify membership details. In some cases, the association website may provide a list of members.

Under Code item 6, registered tax practitioners must not disclose information relating to the affairs of a client, or former client, to a third party unless they have obtained the client’s permission, or they have a legal duty to do so.

Notifications under the breach reporting regime may involve the disclosure of client information. However, as these disclosures are required by law, they will generally be covered by the legal duty exception. As such, breach reporting disclosures will be compliant with Code item 6.

The TASA, including the breach reporting obligations and Code item 6, does not override the law relating to legal professional privilege (LPP). As such, registered tax practitioners should consider whether LPP applies before providing information to the TPB and associations and if so, whether they wish to waive LPP.

The TPB will adopt a transitional approach to enforcing compliance with the breach reporting obligations, focusing first on consultation, education and building awareness, and making improvements in voluntary compliance, supervisory and regulatory systems.

A failure to comply with any of the breach reporting obligations is a breach of s. 8C of the Taxation Administration Act (which makes it an offence to refuse or fail to notify the TPB when and as required under a taxation law) and of Code Item 2 (the registered practitioner must comply with the taxation laws in the conduct of their personal affairs). It is also a factor that may be taken into consideration when determining whether a registered tax practitioner continues to meet the ‘fit and proper’ registration requirement.

Each breach will be considered on a case-by-case basis. The TPB will take a pragmatic and risk-based approach to assessing non-compliance and determining the appropriate compliance action to take.

A significant breach reported by a registered practitioner will not automatically trigger a formal investigation.

The TPB will undertake a preliminary analysis of the breach notification, make relevant enquiries and use information available to us to assess and validate the potential breach and mitigate the risk of frivolous, vexatious or malicious claims.

In deciding whether to commence a formal investigation, the TPB will consider several factors including, but limited to, the following:

![]() Important

Important

When making a report, tax practitioners will need to identify themselves to the TPB to comply with their obligations. That is, breaches cannot be reported anonymously.

Subject to the passage of Treasury Laws Amendment (Tax Accountability and Fairness) Bill 2023, tax practitioners may be eligible for the extended tax whistleblower protections that are proposed to commence from 1 July 2024. These proposed changes seek to provide protections for disclosures by eligible whistleblowers to the TPB relating to the misconduct of tax practitioners. Eligible whistleblowers will have their identity protected, unless it is to an authorised body, or with the whistleblower’s consent.

The draft materials contain six case studies. These are briefly summarised below (see the ED for the full case studies).

David is one of two nominated supervising agents of a registered tax agent company and employs 10 staff to provide tax agent services on behalf of the company.

The other nominated supervising agent went on maternity leave. The remaining staff all have less than 2 years’ experience. David did not nominate a replacement supervising agent.

David received client complaints about the quality of work. David discovered that a number of staff oversights and errors had occurred, quality checks and controls had not been updated to reflect the change in supervising agents, and staff training had ceased.

David had reasonable grounds to believe that the company had breached its ongoing registration requirement to have a sufficient number of individual registered tax agents to provide tax agent services to a competent standard and to carry out supervising arrangements, and as such, was also in breach of Code item 7. David also had reasonable grounds to believe the breach was significant given that the breach resulted in material loss to the clients, a number of clients were impacted, the ability for the company to provide a competent service was impacted and the company’s arrangements to ensure compliance with the Code were inadequate.

![]() Note

Note

As seen in this example, the registered tax practitioner that is the subject of the mandatory notification may be a registered company or partnership, i.e. practitioners are not limited to reporting significant breaches of an individual practitioner.

Ivan is the sole director of a registered tax agent company. Over 12 months, Ivan lodged false BAS without the knowledge or authorisation of more than 10 clients. The ATO cancelled the lodgments.

Ivan subsequently misappropriated client refunds by nominating them to be paid into his own bank account. Further, he put a number of clients at risk when he shared his credentials used to access ATO systems with another individual.

Ivan was aware that he had breached the Code, or had reasonable grounds to believe that he had breached the Code and the breach was significant, nothing the:

Samantha is an employee of a registered tax agent company. The company received a complaint from a new client that identified several issues concerning BAS services provided by Samantha:

After further investigation, the company discovered that this was a once off occurrence and no other clients had been impacted.

While Samantha’s behaviour may be considered to be a breach of Code item 7 as she had failed to provide tax agent services competently, the breach does not equate to a significant breach of the Code, noting the breach:

Colin is a registered tax agent in a medium sized accounting firm. Colin became aware, through former clients of a former colleague, that the former colleague has been depositing client tax refunds into his own personal business account. The tax practitioner has breached Code Item 3 as he has failed to account to clients for money held on trust.

Colin is also aware that the former colleague has been misleading clients into believing their tax returns had been lodged and advising them that they owed tax, money which was then paid to the tax practitioner, and used for the tax practitioner’s own benefit.

Colin followed up these complaints by checking the firm’s working files and online records which confirmed false or fraudulent lodgments.

Colin has reasonable grounds to believe that the other agent has breached multiple Code items and the breaches are significant, taking into account the following:

Brittany attends monthly discussion group sessions with other registered BAS agents. She is also a member of an online forum that discusses new and emerging issues.

At a recent discussion group session, Brittany overheard two attendees gossiping about how their mutual acquaintance, an individual known to Brittany, has been falsifying their CPE certificates and had made false statements to the TPB to hide the fact that they had not completed their CPE.

Brittany made no further enquiries regarding what she had overheard. She also did not have any independent evidence to suggest that the individual had in fact falsified their CPE certificates.

While Brittany thinks that the conduct may equate to a significant breach of the Code, her belief is founded solely on the gossip overheard at the group discussion session. She would not be considered to have reasonable grounds to believe that the individual had breached the Code.

Tamara is a registered tax agent in a large well-known accounting firm. Max, a registered tax practitioner in another leading accounting firm known to be in direct competition with Tamara’s firm, recently took over one of her clients. Tamara was unhappy to have lost this client.

Tamara overhears a discussion between colleagues regarding the fact that the client’s change in firms had come as a surprise given the rumours that had been circulating that Max had been involved in fraudulent tax claims.

Tamara decides to report a breach of the Code. The accompanying information provides very little detail and contains a number of statements that do not appear to be supported in any way.

The TPB makes initial enquiries with Tamara. It becomes clear that she is basing her view solely on the hearsay, speculation or the unsubstantiated opinion of her colleagues. The history to the takeover and competition between the firms may also have a bearing on the credibility of the notification made and increases the potential for it to be vexatious.

The TPB does not have any information to indicate that Max has a history of non-compliance with the TASA or taxation laws.

The TPB is not satisfied there are reasonable grounds for the belief that there has been a significant breach. They decide not to commence a formal investigation.

Upcoming webinars >

Download the May Tax Update >

Upcoming workshops by state >

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.