Background

The measure to allow individuals to carry forward their unused concessional contributions (‘CC’) cap from previous financial years to a later year (‘the carry forward rule’) was announced on 3 May 2016 as part of the Government’s Superannuation Reform Package in the 2016–17 Federal Budget.

The measure is contained in Schedule 6 to the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Act 2016 (‘the Act’) which was enacted on 29 November 2016 and took effect on 1 July 2018. However, due to the design of the measure, any unused cap can only be used from the 2019–20 financial year.

In April 2018, as part of the ALP National Platform — Consultation Draft in which Labor set out its proposed superannuation policies ahead of the 2019 Federal election, it announced that, if elected:

Labor will … remove the catch-up concessional contributions … introduced by the Coalition.

Due to the passage of time and the flurry of election policies from both major parties, some practitioners may have lost sight of the measure, misunderstood its operation or assumed it was no longer available.

The rules

Broadly, the carry forward rule allows individuals to make additional CC in a financial year by utilising unused CC cap amounts from up to five previous financial years, providing their total superannuation balance just before the start of that financial year was less than $500,000.

Effectively, this means an individual can make up to $150,000 of CC in a single financial year by utilising unapplied unused CC caps from the previous five financial years.

Prior to these amendments, if an individual did not fully utilise their annual CC cap in a financial year, they could not carry forward the unused cap to a later year. This rule constitutes an exception to the usual rule when it comes to concessional contributions: ‘Use it or lose it’.

Paragraphs 8.4 and 8.5 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill explain the purpose of the measure:

Annual concessional contributions caps can limit the ability of people with interrupted work patterns or irregular income to accumulate superannuation balances commensurate with those with more regular or steady income. Allowing people to carry forward unused concessional contributions cap amounts for a period of up to five financial years will provide them with the opportunity to ‘catch-up’ if they have the capacity and choose to do so.

The measure ensures that people who have not had the capacity to contribute up to their concessional contributions cap in prior years will be able to make catch-up contributions by targeting it to those individuals who have been unable to accumulate large superannuation balances.

Key points

| Issue |

Explanation |

- Working out amount of unused CC cap

|

The amount of the unused CC cap is the difference between the individual’s CC and the CC cap.

When working out an individual’s unused CC cap for a financial year, the following contributions will need to be taken into account:

- superannuation guarantee (SG) contributions;

- salary sacrificed CC made by the employer on their behalf;

- personal deductible contributions (the notice requirements under s. 270-170 of the ITAA 1997 need to be satisfied).

|

- CC cap increased only by excess amount

|

An individual’s CC cap cannot be increased by more than the amount by which they would otherwise exceed the CC cap. That is, only the exact amount of unused CC cap that is necessary is used, and any remaining unapplied unused CC cap is preserved and continues to be carried forward.

The increased CC cap could allow for the making of additional:

- salary sacrificed CC made by the employer on their behalf;

- personal deductible contributions (the notice requirements under s. 270-170 of the ITAA 1997 need to be satisfied)

|

- Oldest unused CC caps are applied first

|

Amounts of unused CC cap are applied to increase an individual’s CC cap in order from the earliest financial year to the most recent year.

It will therefore be important to track how much of an unapplied unused CC cap is utilised in a later financial year, and when it is utilised. |

- Five-year limit

|

Unused CC cap amounts not utilised after five financial years can no longer be carried forward. |

- $500,000 limit

|

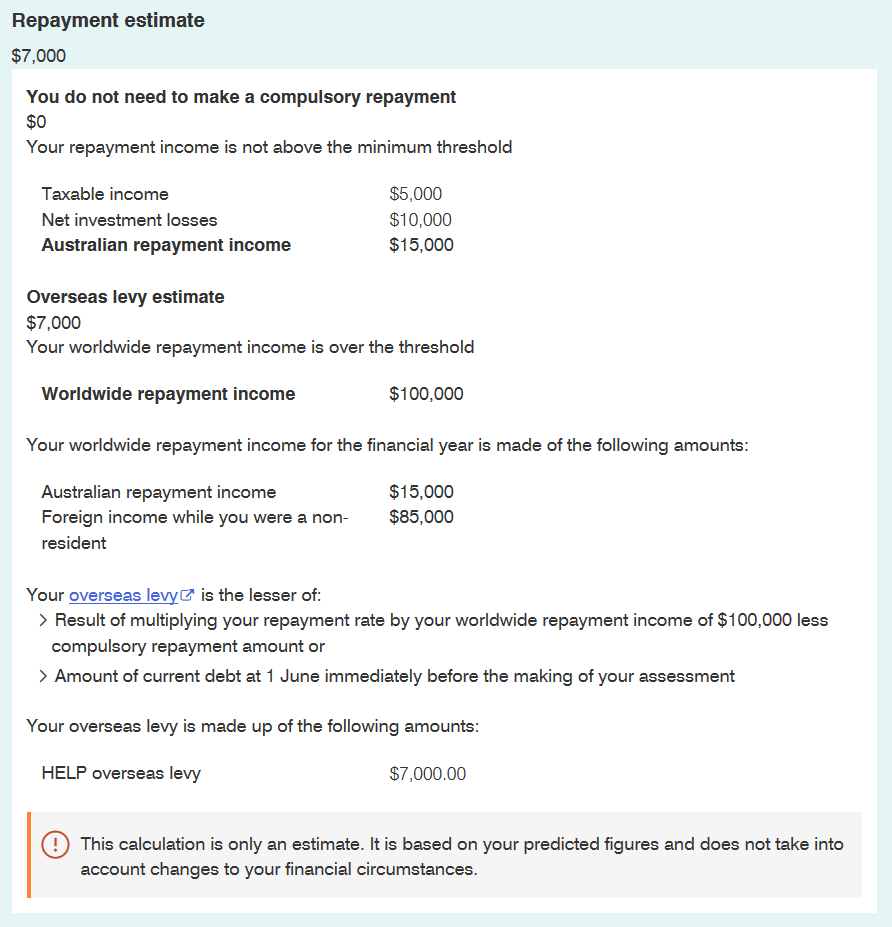

The $500,000 limit on the total superannuation balance (TSB) — a method for valuing all of an individual’s superannuation interests and defined in s. 307-230 of the ITAA 1997 — is applied at the end of the financial year immediately before the year in which any unused cap amounts are utilised, not the year in which the individual does not fully utilise their $25,000 CC cap.

For example, if an individual utilised only $10,000 of their $25,000 CC cap in each of 2018–19 and 2019–20, carried forward the unused caps of $15,000, and fully utilised them in the 2020–21 financial year by making a personal contribution of $45,000 (thereby resulting in their CC cap for 2020–21 increasing to $45,000), the $500,000 limit is applied to the TSB as at 30 June 2020.

If they have a TSB of more than $500,000 as at 30 June 2020, they will not be able to apply the unused caps from 2018–19 and

2019–20 in 2020–21. However, if their TSB later falls below $500,000, they will again be eligible to increase their CC cap by applying the unused CC caps from 2018–19 and 2019–20, but only until 2023–24 and 2024–25 respectively (see Table A below). |

- Eligibility applies to utilising unused caps, not carrying them forward

|

Any individual can carry forward their unused CC cap (i.e. Year 1) to a later financial year (but for no more than five years).

But when the time comes to use it in a later financial year (say, Year 2), they may not be eligible to utilise the unapplied unused CC cap due to the size of their superannuation balance just before the start of Year 2.

Note Note

They may, however, become eligible again in a later financial year (i.e. Year 3, Year 4 or Year 5) if their TSB falls below $500,000 just before the start of any of those years.

|

- Cannot access unused caps from 2017–18 or earlier financial years

|

The carry forward rule applies in relation to working out the CC cap for the 2019–20 financial year and later financial years, so only unused cap amounts from the 2018–19 financial year onwards can be carried forward.

In the first year of operation (2019–20), only one year of carry forward applies; in the second year (2020–21), two years of carry forward will apply; and so on until the full five-year carry forward is reached from 2023–24 onwards (see Table B below). |

Unused cap amounts can be carried forward for up to 5 years

Unused CC cap amounts can be carried forward for a maximum of only five financial years, so unutilised CC caps in 2018–19 will expire on 30 June 2024. Table A below sets out the last financial year in which unused caps from earlier years can be applied.

TABLE A

| Unused cap from this income year … |

… can only be applied until this income year |

| 2018–19 |

2023–24 |

| 2019–20 |

2024–25 |

| 2020–21 |

2025–26 |

| 2021–22 |

2026–27 |

| 2022–23 |

2027–28 |

Expressing this another way:

TABLE B

| In this income year … |

… unused caps from these years can be applied |

| 2019–20 |

only 2018–19 |

| 2020–21 |

only 2018–19 and 2019–20 |

| 2021–22 |

only 2018–19 to 2020–21 |

| 2022–23 |

only 2018–19 to 2021–22 |

| 2023–24 |

only 2018–19 to 2022–23 |

| 2024–25 |

only 2019–20 to 2023–24 |

The concessional contributions cap is $25,000 … isn’t it?

The standard CC cap is $25,000. However, the carry forward rule has the effect of increasing the CC cap, so — depending on an individual’s prior years’ SG contributions, salary sacrificed contributions and carry forward CC — their CC cap may be now anywhere between:

TABLE C

| Income year |

Maximum* CC cap with carry forward rule |

| 2019–20 |

$25,000 to $50,000 |

| 2020–21 |

$25,000 to $75,000 |

| 2021–22 |

$25,000 to $100,000 |

| 2022–23 |

$25,000 to $125,000 |

| from 2023–24 |

$25,000 to $150,000 |

* This does not take into account implementing a ‘contributions reserving strategy’ which may increase the CC cap for a financial year even further.

Accordingly, taxpayers and their advisers will need to take extra care to ensure their CC caps are not exceeded.

ATO assistance needed to monitor unused caps

Given the implications that can arise where an individual exceeds their CC cap — including the imposition of excess CC tax — it will be crucial that taxpayers and their advisers be able to access reliable information that tracks an individual’s unapplied unused CC caps. This task will be made infinitely more difficult with the passage of time and the replacement/appointment of new tax agents.

The ATO’s systems will play a vital role in assisting with this process, and ideally would make available the following information:

- the amount of an individual’s unapplied unused CC cap for each financial year starting from 2018–19;

- the cumulative available unused CC cap for the current financial year; and

- after an unused CC cap is applied, the remaining available unused CC cap for each financial year starting from 2018–19 (this is particularly important because the oldest unused CC caps are applied first).

It should be noted that the information that the ATO could display relies heavily on the accurate and timely reporting from superannuation funds. If there are delays from the funds or if a client has an SMSF then there may be delays in this information updating any superannuation or contribution caps balances that the ATO can display. This may impact an individual’s ability to see a timely or accurate view of their available cap space.

The ATO has recently advised us that:

We are aware of this potential requirement and are currently considering this functionality. We will advise in the near future when this may be able to be developed and made available.

Examples

Example — Increased concessional contributions cap

Based on Examples 8.1 to 8.3 from the Explanatory Memorandum

In the 2018–19 financial year, Layla’s employer made concessional superannuation guarantee (SG) contributions of $10,000 on her behalf to her superannuation fund. Layla did not make any deductible personal contributions to her fund.

The CC cap for the 2018–19 financial year is $25,000. Layla’s unused CC cap amount for the 2018–19 financial year is therefore $15,000.

Between the 2018–19 and 2023–24 financial years, Layla’s CC and available unused CC cap are as follows:

|

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

| Concessional contributions |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$40,000 |

| Available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

| Cumulative available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$30,000 |

$45,000 |

$60,000 |

$75,000 |

$60,000 |

2023–24

In the 2023–24 financial year, Layla makes a deductible personal contribution of $30,000 in addition to her employer’s concessional SG contribution of $10,000 on her behalf. At the end of 30 June 2023, Layla had a total superannuation balance of less than $500,000.

Assuming the CC cap is $25,000 (for all years between 2018–19 and 2023–24), Layla will have exceeded this cap by $15,000. However, Layla will be able to increase her CC cap for the 2023–24 financial year by using $15,000 of unused concessional contributions cap from the 2018–19 financial year.

2024–25

In the 2024–25 financial year, Layla makes a deductible personal contribution of $20,000 in addition to her employer’s concessional SG contribution of $10,000 on her behalf. At the end of 30 June 2024, Layla’s total superannuation balance was still less than $500,000.

|

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

| Concessional contributions |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$40,000 |

$30,000 |

| Available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

— |

| Cumulative available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$30,000 |

$45,000 |

$60,000 |

$60,000 |

$55,000 |

Assuming the CC cap is $25,000, Layla will have exceeded this cap by $5,000. However, Layla will be able to increase her CC cap for the 2024–25 financial year by using $5,000 of her unused CC cap from the 2019–20 financial year. The remaining $10,000 unused concessional contributions cap from the 2019–20 financial year cannot continue to be carried forward. This is because in the 2025–26 financial year it would be outside of the five-year carry forward period.

Example — $500,000 total superannuation balance

Example 8.4 from the Explanatory Memorandum

In the 2021–22 financial year Ashlea intends to use her unused CC cap amounts to make CC of $45,000, on top of her employer’s concessional SG contribution of $5,000.

At the end of 30 June 2021, Ashlea had a total superannuation balance of $480,000 and unused concessional contribution cap amounts from the previous three financial years. She is therefore eligible to make an additional concessional contribution in the 2021–22 financial year.

|

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

| Concessional contributions |

$5,000 |

$5,000 |

$5,000 |

$50,000 |

| Available unused cap |

$20,000 |

$20,000 |

$20,000 |

— |

| Cumulative available unused cap |

$20,000 |

$40,000 |

$60,000 |

$35,000 |

Assuming the CC cap is $25,000 for the 2021–22 financial year, Ashlea will have exceeded this cap by $25,000. However, Ashlea will be able to increase her CC cap for the 2021–22 financial year by using the full amount of her unused concessional contributions cap from the 2018–19 financial year, plus $5,000 of unused cap from the 2019–20 financial year.

At the end of 30 June 2022, Ashlea now has a total superannuation balance of $530,000. This means that Ashlea will not be able to increase her CC cap using unused concessional contribution cap amounts in the 2022–23 financial year.

However, if Ashlea’s total superannuation balance later falls below $500,000 she will again be eligible to increase her concessional contributions cap by accessing her unused concessional contribution cap amounts from the five years prior to the year that she is now eligible to make further contributions.

Planning opportunities

Who should consider using the carry forward rule?

High-income earners typically maximise their CC by contributing the full $25,000 each year, so they are unlikely to have any unused CC caps from earlier financial years.

Accordingly, this rule will suit individuals who:

- have not fully utilised their CC caps in the 2018–19 financial year or a later financial year, such as lower income earners or those who are on unpaid leave for all or part of the year or do not work for the full financial year; and

- have less than $500,000 at the end of the financial year immediately preceding the year in which the unused unapplied CC caps will be applied;

- may wish to contribute additional amounts to superannuation;

- may wish to defer the making of a deductible contribution to a year in which they expect to have additional taxable income which could result in a higher marginal tax rate applying.

Capital gains or other additional taxable income in a later financial year

Case study

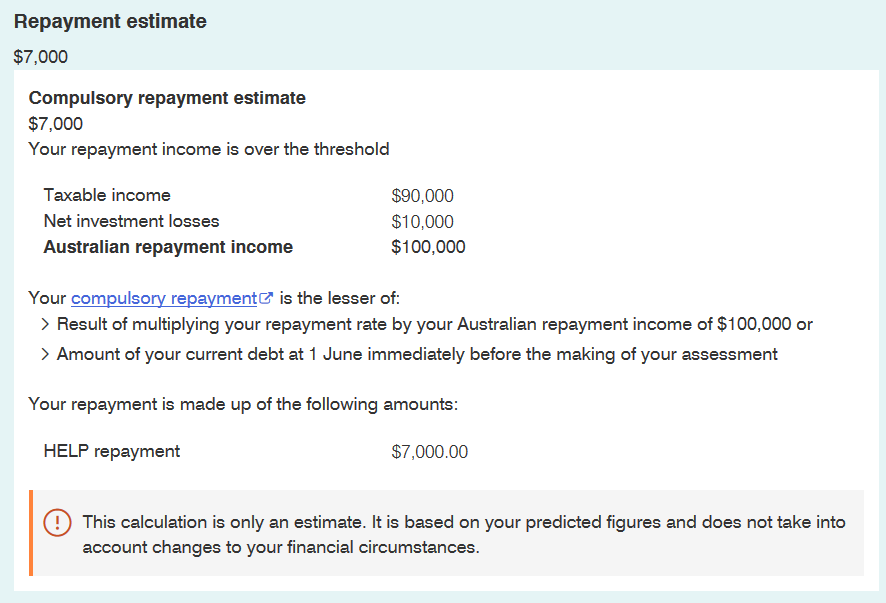

A taxpayer earns an annual salary (excluding SG contributions) of $105,263. Their employer pays concessional SG contributions of $10,000 each year. In the 2021–22 financial year, the taxpayer makes a gross (discount) capital gain of $200,000 (taxable capital gain is $100,000 after applying the CGT discount) and has less than $500,000 in superannuation as at 30 June 2021.

They are considering using the carry forward rule to make additional personal deductible contributions in 2020–21. Without the carry forward rule, the taxpayer can make a personal deductible contribution in 2021–22 of only $15,000 without exceeding their CC cap; with the carry forward rule this can be increased to $50,000.

|

Without carry forward rule |

With carry forward rule |

Assessable income — salary

|

$105,263 |

$105,263 |

| Discount capital gain |

$100,000 |

$100,000 |

| Personal deductible contributions |

($15,000) |

($50,000) |

| Taxable income |

$190,263 |

$155,263 |

| Tax on taxable income* |

$58,715 |

$44,944 |

| Tax saving |

|

$13,771 |

* The Medicare levy has been ignored for the purpose of simplicity.

By claiming a deduction for the personal contribution using the carry forward rule, the taxpayer’s taxable income remains within the same tax bracket, ensuring that the capital gain is taxed at the marginal rate of 37 per cent rather than the one-off increase in taxable income causing the taxpayer to move into the 45 per cent tax bracket.

By using the carry forward rule, the taxpayer has been able to increase their personal contribution from $15,000 to $50,000 in 2021–22, resulting in a tax saving of $13,771.

The utilisation of the unused caps may be summarised as follows:

|

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

| Concessional contributions |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$10,000 |

$60,0001 |

| Available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

| Cumulative available unused cap |

$15,000 |

$30,000 |

$45,000 |

$10,0002

(see below) |

NOTE 1

This comprises the employer’s concessional SG contribution of $10,000 plus the personal deductible contribution of $50,000. The total CC of $60,000 exceed the 2021–22 CC cap of $25,000 by $35,000, so the CC cap is increased by $35,000. The actual contributions of $60,000 utilise the unapplied unused caps from

2018–19 and 2019–20 (each $15,000) and $5,000 of the unused cap from 2020–21 resulting in no excess CC for the 2021–22 financial year.

NOTE 2

The taxpayer has not fully utilised their unapplied unused cap from 2020–21. With the carry forward rule, they could have personally contributed a further $10,000 of CC (in addition to their personal contributions of $50,000 and the employer’s SG contributions of $10,000), thereby increasing the maximum available CC cap by $45,000 to $70,000. This would have resulted in no unused cap remaining at the end of 2021–22.

The unused caps have been applied as follows:

| Income year |

Cap used |

Unused cap |

Used in 2021–22 |

Carry forward |

| 2018–19 |

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

| 2019–20 |

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

$15,000 |

— |

| 2020–21 |

$10,000 |

$15,000 |

$5,000 |

$10,000* |

| 2021–22 |

$25,000 |

— |

— |

— |

* This unused cap can be carried forward until 2025–26.

Reminder

Reminder

CC can only be made by, or on behalf of, an individual who is eligible to have CC. That is, they must:

-

-

- be aged less than 65 years; or

- pass the ‘work test’ if they are aged 65 to 74 years, which requires them to be gainfully employed (an exception applies from 1 July 2019 for individuals who have a TSB of less than $300,000): see 7.04 of the SIS Regs 1994;

- have sufficient taxable income if they intend to claim the CC as a deduction against their taxable income — the amount of any personal contribution that exceeds the amount of taxable income is non-deductible and treated instead as a non-concessional contribution.

Final observations

As with anything related to superannuation, the rules are complex rules and conditions always apply because of the concessionally-taxed environment proffered by Australia’s superannuation laws.

Notwithstanding this, the carry forward rule is a valuable measure and is expected to be availed by many eligible taxpayers with the following benefits:

- the ability to utilise otherwise unapplied unused CC caps;

- the ability to increase amounts held in superannuation;

- the potential to increase deductions for personal contributions, beyond the standard $25,000 cap; and

- the potential to move deductions for personal contributions to a later financial year which may suit the timing of an expected higher taxable income.

Further info and training*

Join us at the beginning of each month as we review the current tax landscape. Our monthly Online Tax Updates and Public Sessions are excellent and cost effective options to stay on top of your CPD requirements. We present these monthly online, and also offer face-to-face Public Sessions at 18 locations across Australia. Click here to find a location near you.

Online training

Online training

Face to face sessions

Face to face sessions

These are only a few of our Public Session options. Click here to find a location near you.

^We will move these sessions to online delivery in the case of restrictions or safety concerns. Your safety is of utmost importance to us.

Tailored in-house training

Tailored in-house training

We can also present these Updates at your firm (or through a private online session) with content tailored to your client base – please contact us here to submit an expression of interest or visit our In-house training page for more information.

Our mission is to offer flexible, practical and modern tax training across Australia – you can view all of our services by clicking here.

*This section was revised on 19 July 2021 to reflect our latest training sessions.

Tailored in-house training

Tailored in-house training