[lwptoc]

In May, the Federal Court handed down its decision in Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd v FCT [2021] FCA 523. It established that for the purposes of determining whether an employer has provided a ‘car parking fringe benefit’, either:

- the primary place of employment of the flight and cabin crew is on the aircraft, and not in the airport terminals; or

- there was no primary place of employment on a particular day.

Accordingly, the provision of car parking spaces at the airport does not constitute the provision of a car parking fringe benefit.

This article will revisit the general legislative definition of a car parking fringe benefit before considering the Court’s interpretation in the Virgin decision. Further the article will look at the Commissioner’s draft views in relation to car parking fringe benefits which the ATO anticipates it will soon finalise.

What is a ‘car parking fringe benefit’?

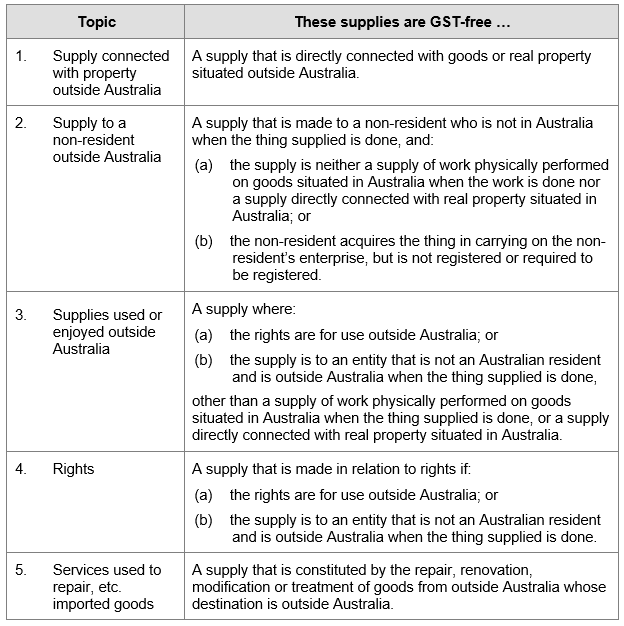

Section 39A of the FBTA Act sets out when a ‘car parking fringe benefit’ has been provided.

In summary, an employer provides a ‘car parking benefit’ on a particular day when, in relation to one or more daylight periods:

- a car is parked at a work car park for the minimum parking period;

- an employee uses the car in connection with travel between their place of residence and primary place of employment at least once on that day;

- the work car park is located at or in the vicinity of the primary place of employment, on that day;

- a commercial parking station is located within a one kilometre radius of the work car park used by the employee;

- the lowest representative fee charged by any commercial parking station for all-day parking within a one kilometre radius of the work car park exceeds the car parking threshold;

- the parking is provided to the employee in respect of their employment; and

- the parking is not excluded by the regulations (for example, a car space provided to eligible disabled employees).

What is the primary place of employment

Section 136(1) defines an employee’s primary place of employment in relation to a day as meaning business premises, or associated premises, of the employer or an associate of the employer, where:

- if the employee performed employment duties on that day — on that day; or

- in any other case — on the most recent day before that day on which the employee performed employment duties,

those premises are or were:

- the sole or primary place of employment of the employee; or

- otherwise the sole or primary place from which or at which the employee performs employment duties.

The Virgin decision considers an employee’s primary place of employment in circumstances where the employee performs employment duties in multiple locations, including a mode of transportation, on a particular day.

Other definitions

The following are relevant definitions contained in the FBTA Act or the ITAA 1997.

All-day parking means parking of a car for a continuous period of six hours or more during the ‘daylight period’ — i.e. after 7.00 am to before 7.00 pm — on that day.

Car means a motor-powered road vehicle (including a motor car, sports utility vehicle, van or utility, but not a motor cycle) designed to carry a load of less than one tonne and fewer than nine passengers. The car must be:

- owned by, or leased to, an employee or their associate;

- made available to an employee or their associate; or

- related to a car benefit provided on that day.

Car space refers to a space in which a car can reasonably be parked, and does not need to be on bitumen or a paved surface or marked as a parking bay.

Commercial parking station, in relation to a particular day, means a permanent commercial car parking facility where any or all of the car parking spaces are available in the ordinary course of business to members of the public for all-day parking on that day on payment of a fee, but does not include a parking facility on a public street, road, lane, thoroughfare or footpath paid for by inserting money in a meter or by obtaining a voucher. See draft Ruling TR 2019/D5 for the Commissioner’s preliminary views on what constitutes a commercial parking station.

Daylight period in relation to a day is the period after 7 a.m. and before 7 p.m. on that day.

Minimum parking period is a combined parking period of more than four hours (the four hours do not need to be continuous).

On-street parking is parking on a street, road, lane, thoroughfare or footpath paid for by inserting money in a meter or by obtaining a voucher.

Place of residence is a place where a person resides or has sleeping accommodation. It does not need to be the employee’s usual or normal residence. It could be a place at which the employee sleeps on a temporary basis — e.g. a hotel or serviced apartment.

Work car park is a business premises or associated premises of the provider, where cars are parked in a car space on that day. It does not need to be a commercial parking station and includes an area where pool cars or fleet cars available for employees to use are parked. A business may have multiple locations where car spaces are provided to employees — each is considered to be a work car park. (See TR 2000/4 for the Commissioner’s views on business premises and associated premises.)

The car parking threshold for each income year is published by the ATO here. It is $9.25 for the 2021–22 FBT year.

Virgin Australia — car parking fringe benefits not provided

The facts of the case

The Taxpayers were Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd and Virgin Australia Regional Airlines Pty Ltd.

The Taxpayers, whose principal business activity was the transportation of passengers on aircraft, had contracted with commercial car park operators at Sydney, Brisbane and Perth airports for the provision of car parking spaces at those airports. The Taxpayers provided the car parking facilities to the flight and cabin crew employees (the employees) by giving them access cards to the car park at the airport nearest to the location where the employees lived (the origin airport).

During their rostered shifts, the employees performed their duties at both airport terminals and on the aircraft. The type of duties undertaken prior to departure and following arrival of the aircraft were central to the question of whether the airport terminal was the ‘primary place of employment’ of the employees.

The flight crew employees undertook a number of duties at airport terminals, including:

- signing on at the crew room at least 60 minutes prior to their first scheduled domestic flight (90 minutes for international flights);

- reviewing various pre-flight operational information (approximately 15-20 minutes);

- performing pre-flight procedures once onboard the aircraft (30 minutes);

- completing a post-flight administrative checklist upon arrival;

- remaining onboard for the next flight or changing aircraft if required (the flight crew waited in the terminal if they needed to change aircraft during the day);

- after their final rostered flight of the day — performing post-flight checks and signing off at the crew room in the terminal (which may or may not be the terminal at the origin airport).

The duties of cabin crew employees included:

- attending a pre-flight briefing (approximately eight minutes);

- boarding passengers (approximately 20 minutes);

- upon arrival, disembarking passengers from the flight and cleaning the aircraft (approximately 30 minutes);

- remaining on-board for the next flight or changing aircraft if required (in which case they would wait in the terminal in between);

- signing on and off their shifts at the crew room in the relevant terminal (which may or may not be the origin terminal).

FBT liability dispute

In calculating their FBT liabilities for the 2012–13 to the 2015–16 FBT years, the Taxpayers treated the provision of all car parking spaces at the origin airport to the employees as a car parking fringe benefit pursuant to s. 39A of the FBTA Act.

The Commissioner assessed the Taxpayers to FBT on the basis that the employees’ ‘primary place of employment’ was their home base airport terminal in Sydney, Brisbane or Perth. The taxpayer objected to the assessment and the objection was disallowed.

In the Commissioner’s reasons for disallowing the objection, the Commissioner stated that it was understood that ‘the [employees] spend most of their time on the aircraft and are rostered for various routes and differing time schedules’.

The contentions

The Taxpayers contended that the employees’ primary place of employment was the aircraft on which they carried out their duties, and that the duties performed at terminals were ancillary to the principal duties performed onboard the aircraft. Therefore their cars were not parked at, or in the vicinity of, their primary place of employment.

The Commissioner contended that the employees’ primary place of employment on each working day was the home base airport terminal at which they signed on for a shift. An employee’s car was parked ‘at, or in the vicinity of’ their primary place of employment on each day the employee used the car park at their home base.

Alternatively, their employees’ primary place of employment was the airport at which they commenced their shift if it was other than the home base terminal. In this case, an employee’s car was parked ‘at, or in the vicinity of’ their primary place of employment on each day the employee used the car park at the airport where they commenced their shift.

The Federal Court decision

The Federal Court, allowing the Taxpayers’ appeal against the Commissioner’s objection decisions, held that the Taxpayers did not provide car parking fringe benefits to the employees.

In cases of domestic flights where the employees worked only on one aircraft on a particular day, as well as on international flights, the employees’ primary place of employment on that day was the aircraft which, for the purposes of s. 39A(1)(f), was not within the vicinity of any of the car parks.

In cases of domestic rosters involving multiple sectors using different aircraft on a particular day, there was no primary place of employment and s. 39A(1)(f) did not arise.

The ‘primary place of employment’

The employees did not have a ‘sole’ place of employment but performed their duties of employment in several places. The question was which of the following locations was their ‘primary’ place of their employment:

- the airport terminal where they commenced duty and attended to pre-flight matters;

- the one or more aircraft on which they were located for the particular day;

- the destination airport terminal or terminals where the aircraft landed;

- the airport terminal where they finished their duty (which was not necessarily their origin airport or the terminal where they commenced duty).

The ordinary meaning of the word ‘primary’ required a determination as to which place of employment was the first or highest in rank or importance. This requires undertaking a qualitative and quantitative exercise to compare the duties performed at each place.

For domestic flights where the employees worked on only one aircraft during the day, their primary place of employment on that day was that aircraft. Most of the relevant employees’ time was spent performing their duties onboard the aircraft and while it was in flight.

This argument was even stronger for international flights, where the time spent onboard the aircraft was likely to be longer.

In both cases, the duties performed by the employees at airport terminals were ancillary to the principal duties which were performed onboard the aircraft. In a quantitative sense, such duties were of a short duration. In a qualitative sense, they were still ancillary to the onboard duties.

Where employees worked on different aircraft on a particular day, the fact that different aircraft were used did not mean that the ‘home base’ airport, nor the terminal where the employees signed on, was the primary place of employment. The amount of time spent performing duties at airport terminals was far outweighed by the time spent performing duties on the aircrafts. Under these rosters, there was no primary place of employment.

Parked at, or in the vicinity of the primary place of employment

Where the employees operated on only one aircraft on a particular day, that was their primary place of employment, which was plainly not within the vicinity of any of the car parks.

Where more than one aircraft was involved on a particular day, there was no primary place of employment and the vicinity question did not arise.

Implications

The outcome of this case may potentially have implications for employers in other industries whose employees perform most of their duties on a mode of transportation — these may include delivery trucks; passenger and freight trains; buses; cargo ships and passenger vessels; hire car drivers; ambulances and similar.

The question to be answered is whether the duties performed at a home depot or home base — where the employer has provided car parking facilities — are merely ancillary to the duties performed elsewhere; that is, where is the primary place of employment?

The Court decision cannot be taken to mean that all employees who work on moving vehicles or other transport have that as their primary place of employment. In each case it must be assessed as to which of the employment duties are principal and ancillary duties and where they are performed. For example, where an employee who does most of their work on aircraft but only when they are stationary and not in flight, the conclusion as to their primary place of employment may be different to that for flight crew.

Of course, a car parking fringe benefit can only exist if all other conditions are met, and no exemption applies.

The ATO anticipates that it will soon finalise its ruling setting out the Commissioner’s views in relation to these conditions. Additionally, from 1 April 2021, the exemption in relation to small business car parking is extended to entities with aggregated turnover up to $50 million.

Draft ruling on car parking fringe benefits

Draft Ruling TR 2019/D5 titled Fringe benefits tax: car parking benefits (the draft Ruling) was issued on 13 November 2019. It sets out the Commissioner’s preliminary views on when the provision of car parking is a ‘car parking benefit’ for the purposes of the FBTA Act.

The ATO expects to finalise the Ruling this month (June 2021). When the Ruling is finalised, it will replace TR 96/26 (withdrawn on 13 November 2019).

When the final Ruling is published, the Commissioner’s revised view on the meaning of the term ‘commercial parking station’ will apply from 1 April 2022.

An updated version of Chapter 16 in the Fringe benefits tax — a guide for employers to reflect the changes will also be published. A draft update for comment was published on 27 November 2019 pending consultation.

In particular, TR 2019/D5 provides guidance on what constitutes a ‘commercial parking station’. The draft Ruling differs from TR 96/26 by recognising that a car park, which satisfies all other requirements, can still be considered a ‘commercial parking station’ even if:

- its contractual terms restrict who may use the car park, provided any member of the public that accepts these restrictions can use the car park;

- its fee structure discourages all-day parking with higher fees.

For a ‘car parking benefit’ to arise, the commercial parking station must be located within a one kilometre radius of the work car park — this will be the case if:

- the closest car entrance to the commercial parking station is within one kilometre of the closest car entrance to the work car park (see 39B);

- to be measured by the ‘shortest practicable route’, which can be travelled by foot, car, train and boat (but not including illegal or impractical shortcuts).

The draft Ruling also takes into account significant Court decisions handed down after TR 96/26 was issued.

The Full Federal Court in Virgin Blue Airlines Pty Ltd v FCT [2010] FCAFC 137 held that:

- For the purposes of determining whether the car park and the primary place of employment are ‘in the vicinity of’ each other, it is the spatial and geographical separation that is significant.

- Geographical ‘encompasses geographical features such as rivers, railway lines, freeways and other physical obstacles which might render a car park and an employee’s primary place of employment near or close as the crow flied but not so in terms of the distance of the shortest practicable route between them’.

The principles set out by the Full Court in FCT v Qantas Airways Ltd [2014] FCAFC 168, and the Tribunal in the earlier decision Re Qantas Airways Limited v FCT [2014] AATA 316, include that:

- A car park is offered to the public where car spaces are available to any member of the public.

- A car park may be a commercial parking station on a particular day even if employees used or could use the parking on that day, or the car park was intended to be used by employees commuting between their place of residence and their primary place of employment.

- A car park may be a commercial parking station on a particular day even if conditions imposed on its use meant employees did not or could not use it.

- A fee must be charged to access all-day parking.

- The lowest representative fee charged cannot be worked out from fees for longer-term parking if users are prevented from entering and exiting the car park on a daily basis during that period.

Further info and training

Join us at the beginning of each month as we review the current tax landscape. Our monthly Online Tax Updates and Public Sessions are excellent and cost effective options to stay on top of your CPD requirements. We present these monthly online, and also offer face-to-face Public Sessions at locations across Australia. Click here to find a location near you.

Our upcoming July Tax Update will cover this topic and what it means for you and your clients. Click here to register for the Online session, or click here to find a public session close to you.

If you’re a current in-house client and interested in this topic, we can tailor your next session to include further coverage of this – just contact your regular trainer or our friendly training operations team through enquiries@taxbanter.com.au.

If you’re not a current client, we can also present these Updates at your firm (or through a private online session) with content tailored to your client base – please contact us here to submit an expression of interest or email us for more information.

Our mission is to offer flexible, practical and modern tax training across Australia – you can view all of our services by clicking here.

Note

Note

Tailored in-house training

Tailored in-house training NOT YET LAW

NOT YET LAW

Useful Resources

Useful Resources