[lwptoc]

Online platforms provide a variety of ways for individuals to earn money or receive benefits. In many cases it is what is commonly known as a taxpayer’s ‘side hustle’, from which the taxpayer reaps some monetary benefit from a skill, passion or hobby separate to the income they earn in their ‘day job’ being their main employment or business.

Examples include:

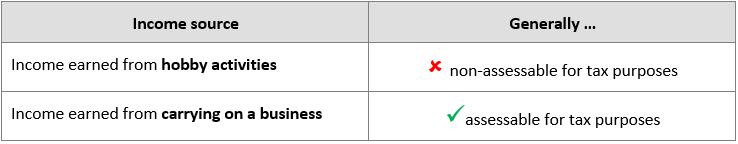

The Australian tax law does not contain a separate set of rules for dealing with income which is initiated by a web-based interaction. The general principles of determining whether a particular amount of money received in exchange for the provision of a good or service is assessable continue to apply in these circumstances. While this article focuses on online activities as a context for discussion, the principles equally apply to side hustles that are derived away from the computer, e.g. by advertising through leaflets, posters or word of mouth.

With the ATO’s data-matching capabilities greater than ever before, it is more important than ever to ensure that income that is properly characterised as assessable is reported in the taxpayer’s tax return.

Assessable income for tax purposes includes ordinary income, which is defined simply as ‘income according to ordinary concepts’ (refer to ss. 6-5 and 995-1 of the ITAA 1997). The general principles underlying ordinary income have been determined by case law. Of relevance for present purposes:

TR 2005/1 provides a number of specific examples regarding various hobbies being treated as a business or otherwise.

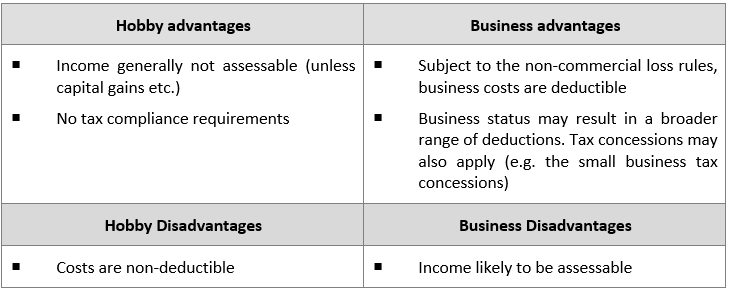

Treatment of an activity as a hobby or as a business may give rise to the following taxation advantages and disadvantages.

Amounts generated in the ordinary course of carrying on an online business will generally constitute ordinary income under s. 6-5. In the online space, this could potentially include:

Under the s. 6(1) definition, the term ‘business’ takes its ordinary meaning, but specifically:

Whether or not a taxpayer is carrying on a business is a question of fact and degree. With no legislative definition of ‘carrying on a business’ the Courts have looked to a number of factors to be considered when determining whether a taxpayer is carrying on a business, including the following:

Warning

Warning

The factors above should be considered in combination, not in isolation, and the Courts have found that no one indicator is decisive. For example, the smaller the scale of the activities, the more important the other factors become.

![]() Website

Website

The ATO has some guidance to assist taxpayers in determining whether online selling activities constitute a hobby or a business: ‘Online selling — hobby or business?’ (QC 28130).

The Tribunal decision in FFYS and FCT [2021] AATA 4844 concerned whether an Airbnb host was carrying on a business in the context of eligibility for JobKeeper payments.

Since 2016, the Taxpayer had used the Airbnb platform to source bookings from paying guests who wished to stay in her home on the Sunshine Coast.

The Taxpayer and her husband remained in the house when guests stayed. In accordance with the Airbnb listing, guests had limited access to the kitchen, and some parts of the house (including the garage) were off-limits. Guest rooms could be locked from the inside but the Taxpayer might access a guest room to service it as required even when it was allocated to a guest.

The Taxpayer estimated she spent up to 18 hours a week on activities associated with the Airbnb guests such as cleaning, gardening, attending to the pool, and actively attending to the Airbnb site.

She reported the modest amount of money she made from the Airbnb listing in her income tax returns as ‘rental income’, and claimed deductions relating to the property against that rental income. The Taxpayer relied on the records built into the Airbnb site, as well as Paypal, the ATO app and her bank statements (i.e. she did not keep separate business records).

The Tribunal found that the acceptance of paying guests into the Taxpayer’s home through the Airbnb website was not carrying on a business for the purposes of the JobKeeper Rules.

The Tribunal listed the following indicia that provided the most weight in support of the Taxpayer undertaking a business:

The Tribunal also accepted that the Taxpayer had a profit-making purpose, however did not give this factor a lot of weight, given the Taxpayer’s unsophisticated approach. The Taxpayer’s rudimentary record keeping was indicative of her not carrying on a business, the Tribunal noting that while good record keeping is a hallmark of a well-run business, a lack of record keeping does not preclude activities from being a business.

Despite indicia pointing both ways, on balance, the Tribunal was not satisfied that the Taxpayer had established that she was carrying on a business at the relevant time. Ultimately, the Tribunal concluded that the Taxpayer was merely repurposing a spare room, and providing mostly conventional domestic services to make some extra money on the side — i.e. the guests were treated as guests in the Taxpayer’s private home.

Implications

Implications

This decision has the impact that the Taxpayer was not carrying on a business for the purposes of the JobKeeper rules. It does not have the implication that the income is not assessable income for the Taxpayer.

This example is broadly based on an example in the ATO fact sheet Online selling — hobby or business?

Carson is moving house soon and he wishes to clear excess tools and car parts from the shed and garage, so he lists various individual items onto Gumtree and Facebook Marketplace. Some of the items sell for more than her buying price, some for less.

He charges buyers postage and receives a total of $3,050.

Carson is not carrying on a business because he:

This example is broadly based on an example in the ATO fact sheet Online selling — hobby or business?

Jo works full time as a landscape gardener. She has always enjoyed making things and, has developed an interest in jewellery-making. She makes pins, neck pieces and earrings in a variety of materials and incorporating found objects. At first she gave away the things she made to friends and family as gifts. However, this year she has established a store online to sell her wares. This cost her $500.

Jo’s jewellery begins to garner a bit of a cult following, and she can hardly keep up with demand. She increases her prices, and in the current income year her sales amount to around $9,375.

Jo still considers this is a hobby, as she only goes out foraging for materials on the weekend and makes jewellery outside of her full-time job as a landscape gardener.

Jo has an Instagram page she has set up, where she posts photos and details about the items for sale. Recently, many influencers have been wearing her jewellery which has made it quite fashionable. Although she doesn’t pay to advertise, she has had more than she has more than a thousand visits per month to her website.

After taking into account the cost of materials, Jo has made a profit of $8,002, from 225 items sold throughout the year.

Based on a consideration of relevant factors, it is likely that Jo is carrying on a business because:

Where it is concluded that Jo is carrying on a business, she will be required to report the income from the online sales as business income and she can claim relevant business expenses as deductions.

This example is adapted from Private Binding Ruling no. 1051892869509.

Is the money received by a Taxpayer from selling off their private collection of plants online considered assessable income under s. 6-5 of the ITAA 1997?

The Taxpayer had a hobby of collecting plants for their own personal enjoyment. The plants were primarily acquired as a gift from their grandparents. Prior to 20XX the Taxpayer had never sold any of the plants.

The Taxpayer made the decision in mid-20XX to start to sell the plant collection as they were unable to continue to look after the plants. The plants are stored in a greenhouse on a property that the Taxpayer previously owned. The Taxpayer does not have an intention of making a profit, the intention was to dispose of the plants.

The plants are primarily sold on eBay via auction. The PBR notes the following additional facts:

No, the money received is not part of the Taxpayer’s assessable income under s. 6-5 of the ITAA 1997 as it does not have the characteristics of a business.

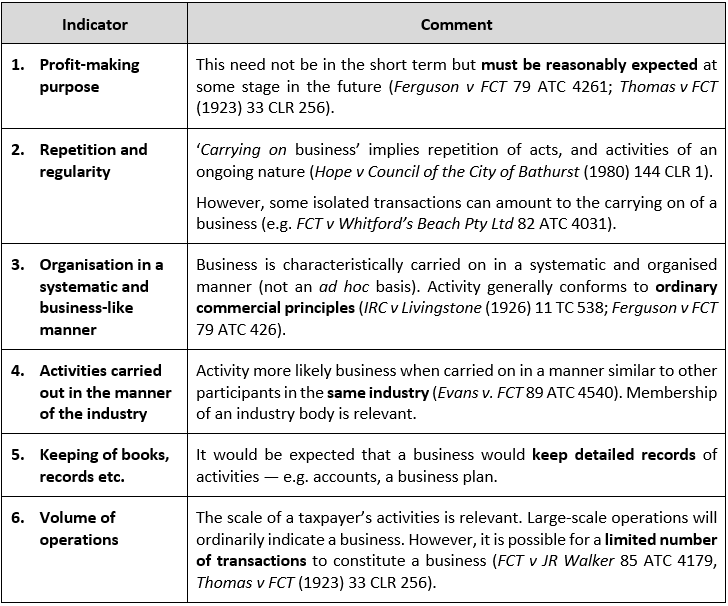

How will the ATO know about this online income? If the ATO do not know about the online income they cannot assess the taxpayer on it right?

The ATO has vast data-matching powers, and it is highly likely that the ATO will already have a taxpayer’s online income information at their disposal.

The ATO collect information from a wide range of third party sources, with more than 600 million transactions reported to the ATO annually. Examples of third-party sources from whom the ATO currently receive information:

The ATO also has powers to collect information for data-matching projects designed to address specific industries, issues or risks.

The list of the ATO’s currrent data-matching protocols is found here.

Need to catch up on the current tax landscape? Join us for an upcoming session!

![]() Tax Fundamentals

Tax Fundamentals

Training intended for juniors, trainees and those returning to the accounting industry.

Melbourne | 2-3 March 2022 | more info >

Sydney | 23-24 March 2022 | more info >

Tax Fundamentals Online training

Tailored in-house training

Tailored in-house training

We can also present general tax updates and specialised topics at your firm (or through a private online session) with content tailored to your client base – please contact us here to submit an expression of interest or visit our In-house training page for more information.

You can view all of our upcoming online training here. Need to catch up on your CPD? Our recordings page hosts all of our past sessions.

Our mission is to offer flexible, practical and modern tax training across Australia – you can view all of our services by clicking here.

Join thousands of savvy Australian tax professionals and get our weekly newsletter.